2 February 2022

Maps

Deeply troubled by world events, I set about basic tasks in the hope that, out of this simple act, I might find something that offers up the best of humanity. So I start to organise my maps. The process begins with a kind of frozen inertia and a doubting mind: what on earth can I get out of this hapless act of self-soothing?

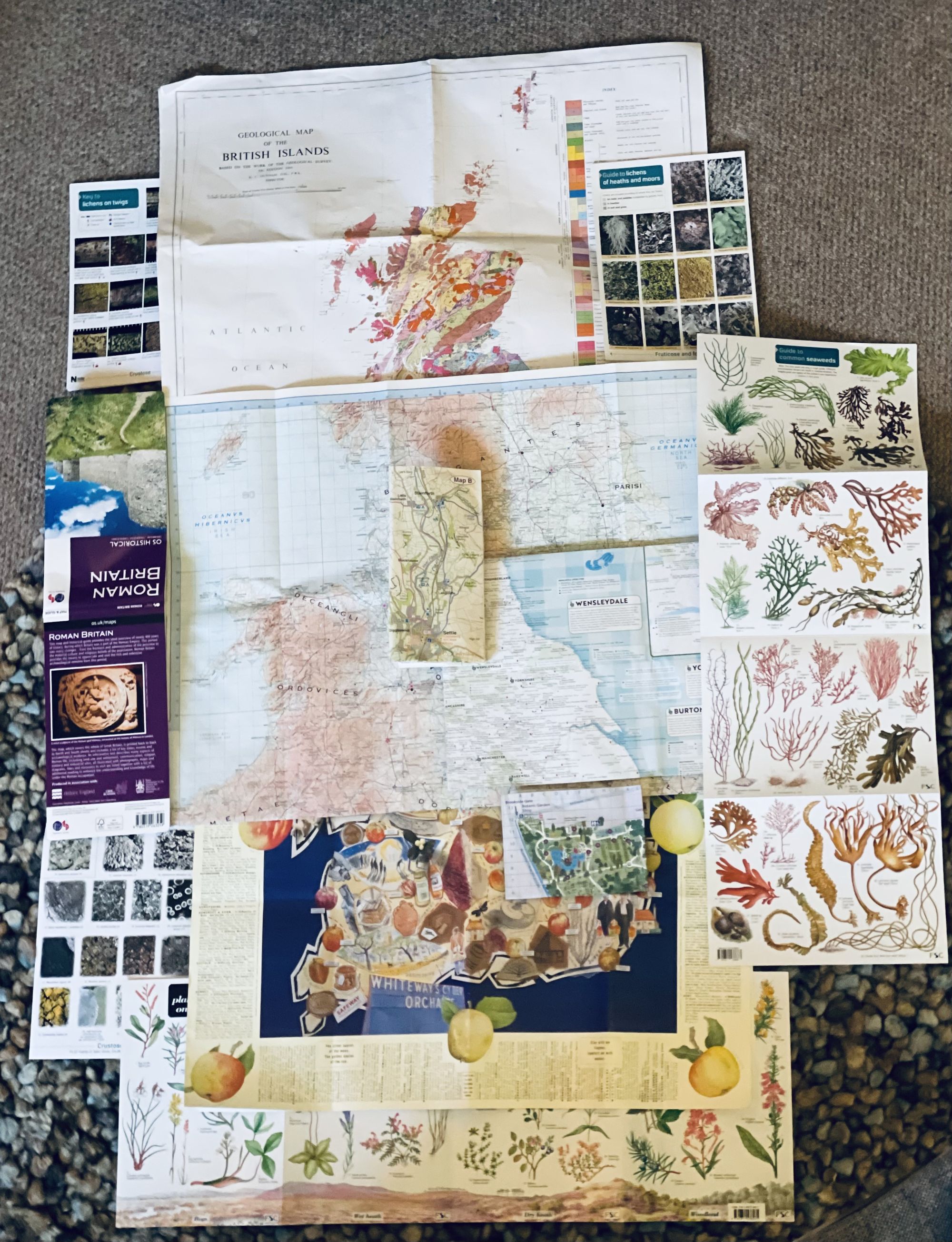

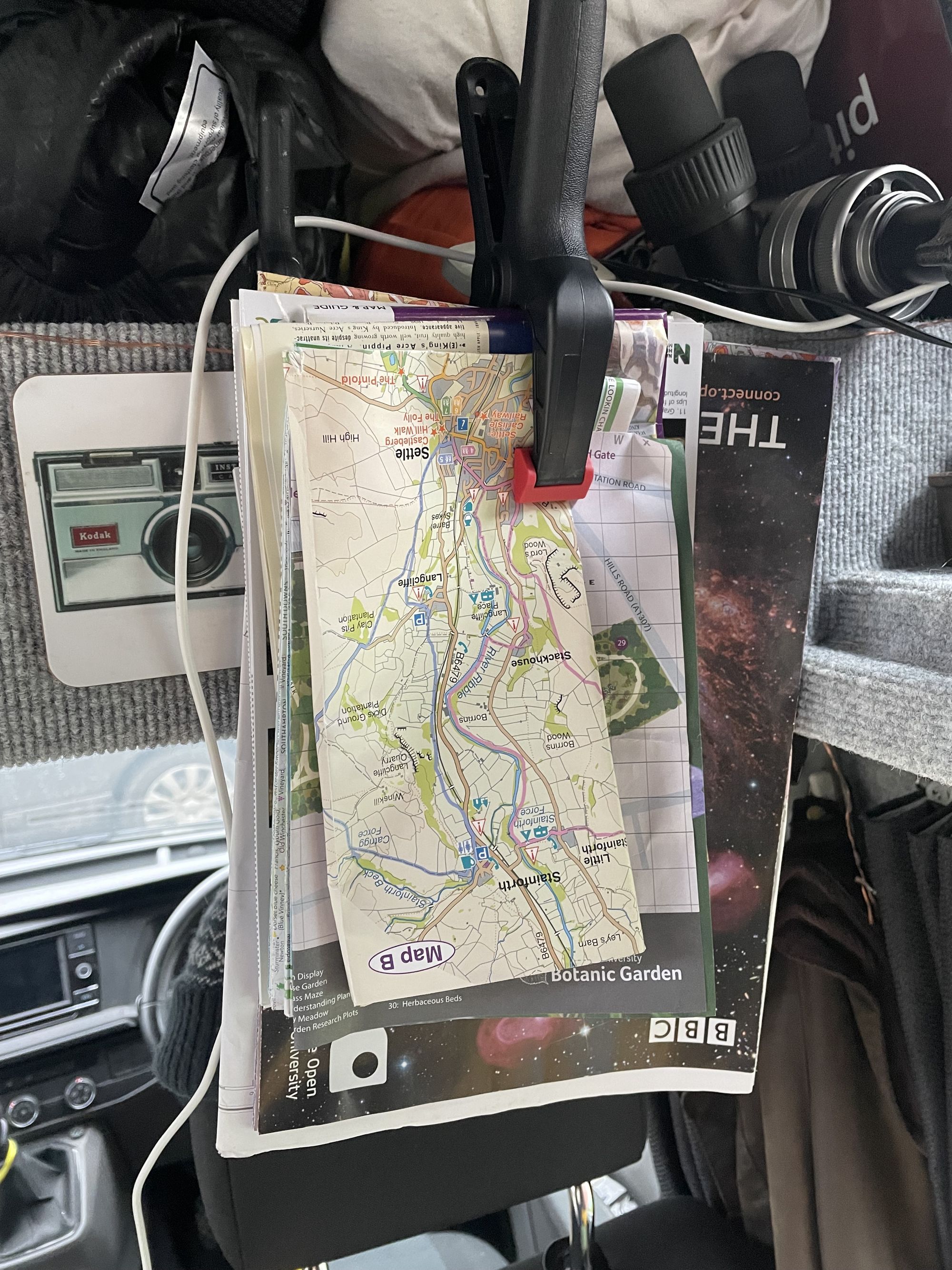

I’ve layered the maps together like the pantiles on a roof. There’s something about the physical act of layering information up with paper - a kind of data archaeology. It can’t be done adequately on a screen or device. Information needs to be visual, tactile and malleable for it to make sense to me.

It’s been done before, of course, by indigenous groups that add meaning to the landscape. Think of the the Songlines of the aboriginal people of Australia - each significant element of their landscape has been woven into a song-story, a memory map that still holds a complex data-set of history, morality, justice and humanity.

On my snug floor, our places become shape-shifting, blurry edged data sets.

I look at my pan-tiled fuzz map. It’s like making a cake - I can choose what ingredients interest me and add them to the mix. Every interaction with my map-mix is nuanced and has its own personal flavour. I see places that are oolitic below the ground with apples called Ashmead’s Kernal above. There are food lovers in Malton during the festival, and fruit lovers at Sulgrave on Apple Day. Nearby are towns that harbour a golden lichen called Xanthoria Parietina, whose estuaries hold Twisted and Channelled Wrack. No doubt all these things have found their way into the limed mortar on the walls of the flint-knapped churches of the south, or along the arris of a hand-made clay brick in Flemish bond - so say my maps.

There are churches in Norfolk that have round towers with basket-weave windows, and town halls in Lancashire with soot-wicking ceramic facades. Romans own the spa towns, Saxons the burgh’s, the Celts the spring and yew. Or perhaps it’s a bit more complex than that, say in the places where the yew shadows the Saxon church, built on a spring full of broken swords, with a Roman shrine re-purposed as a stoop. I don’t have a map of that.

I’ve folded in some gnarled maps from an old builders manual and added some snapshots from Alec Clifton-Taylor’s Pattern of English Building. The words they use take me into a world of wattle and wonder in places that I might otherwise drive through without stopping. My quilted map forces me to stop and research these places and look closely at them.

Their walls might be part of a barmkin or bawn or they could be battered, raggled, raked or ramped. They might have fixtures with a zoological slant: a bull-nosed sill, bullseye window, catslide, catwalk, crowstep, herringbone, ratcourse, dog-leg, swan-neck or frog. For those of an anatomical bent, there are places with a profusion of dentils, groins and ribs, with details being eared, lugged or shouldered. People with a culinary disposition might visit a house in Malton with hungry joints, feasting on edge roll with egg and dart or fillet with jamb, finished off with scalloped capitals and a final dash of seasoning from a pepperpot finial. Its roof could have a hip, helm, gable or mansard. It might be covered in thatch or stone, and if in slate, it could be Burlington, Welsh Blue or Westmorland Green. Such slates might be arranged in standard or random diminishing courses, mitred or wrestled.

I look across the maps with Clifton-Taylor spectacles and hear his words:

“About an hour after leaving London, red brick gives place to stone, grey, yellow or golden brown. Whether we have set out from Paddington or Euston, from King’s Cross or St. Pancras, whether we have followed the Great North Road, the Bath Road or Watling Street, we do not have to be very observant to notice the change. Sometimes it takes place quite suddenly; at others there is a moment of transition, as at Wheatley in Oxfordshire, where old buildings of grey stone are roofed with mellow red tiles, proclaiming the proximity of both stone and clay. But presently in all these directions the change occurs.”

Every time I pull these maps and guides out - there’s a pushing aside of tables and chairs, the making of a space to ponder. Then a rustling, unravelling and stroking of paper, and the squeezing out of places caught within the folds. There’s the joy of anticipation at where this geographical mead might take me next.

Something deep inside, call it instinct if you will, tells me that we should hang onto the grit of this diversity, as if our lives depend on it. I’m not sure why, but my instinct feels right.

Next diary entry:

More about this Digest:

Can you help support me on my journey by becoming a Member?

Help keep Woody on the road and support the Genius Loci Digest.

Explore th Benefits

Member discussion