Welcome!

I’m an architectural photographer and writer.

On my van-life travels through the British Isles I’m building up a word and photo-hoard of material culture that celebrates the value and distinctiveness of our built heritage and contributes to a sense of place.

My van is my time-machine, it gives me fresh perspectives on our remarkable places, shared here on a weekly basis. 📸🚐🏛

🏛 Missed the last Digest? Here it is.

🚐 View Digest Archive here.

Thanks to all for your continued support and encouragement. It takes a day a week to produce this digest. With your support, I’m able to keep this digest free and public facing. 📸🏛🚐

❓Can you help support this digest? More here. ℹ️

Photo-hoard

Divine combination: the Anglo Saxon C9th nave (left) and the C10th tower (right) at St. Peter, Barton-upon-Humber, Lincolnshire.

Words

‘For, indeed, the greatest glory of a building is not in its stones, nor in its gold. Its glory is in its Age, and in that deep sense of voicefulness, of stern watching, of mysterious sympathy, nay, even of approval or condemnation, which we feel in walls that have long been washed by the passing waves of humanity […] it is in that golden stain of time, that we are to look for the real light, and colour, and preciousness of architecture.’

John Ruskin, The Seven Lamps of Architecture.

Observations

Barton Brick

Once I gave a masterclass on photography, and during the first session I showed the class a photograph of a brick wall and told them that it was my finest image. The silence in the room was something to savour - the class quite literally ‘hit a brick wall’ in terms of understanding why the image was so special. I showed them the photograph to make a dent in their rusty perception.

The humble brick isn’t as hard faced as we think, it’s full of holes. When we look again at the brick photo the hard surface of our indifference starts to evaporate and we become as porous to ideas as the brick is to air and water. I then tell the class that the brick is one of the most human of components: it is sized to fit the hand. I tell them that each and every hand-made brick is unique with its own character. It has its own texture and colour dependent upon where the clay is from. They are blessed with irregularity. I quote my guru Alec Clifton Taylor:

“Irregularities give life to a surface, and render it a pleasure to contemplate. This is a law of nature. The blades of grass in every field, the leaves on every tree, differ minutely from one another while adhering to a general conformity. The differences from brick to brick might also be scarcely perceptible, yet they were sufficient to break up the flatness of the finished wall and save it from dullness.” (Pattern of English Building).

I then show them a watercolour. It’s entitled “Study of a Piece of Brick, to Show Cleavage in Burnt Clay.” It shows a fragment of brick that has been weathered with time, delaminated and pitted, it holds upon its surface a green mossy covering that is reminiscent of a forest canopy seen from an aeroplane. This humble fragment has folded within it many things that are holy to our senses: the irregularity, the colour, the organic forms. The watercolour is by John Ruskin. During a time of unprecedented change, every brush stroke is a little protest against the shallowness of his world. Ruskin could see like no other, and anchored his wellbeing in a piece of fired clay.

The water colour reveals an ordered and nested complexity that reverberates through things that have natural appeal to us - whether it be a vast canopy of trees, or the surface of a brick; or the surface of a brick that looks like a vast canopy of trees. The appeal lies in its fractal nature - natural shapes and forms that have developed organically over time - just like the buildings in Barton-upon-Humber.

“Study of a piece of Brick, to Show Cleavage in Burnt Clay” (1882) by John Ruskin

Newall, Christopher (with contributions by Christopher Baker, Conal Shields, and Ian Jeffrey. John Ruskin Artist and Observer. Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada; London Paul Holberton Publishing, 2014. No. 83. [Review in the Victorian Web]

Barton-upon-Humber Bricks

The Brick Reveal

Beneath the rendered serenity (see photo below) lies an archeologists delight. It reveals a few chapters behind the story of the building which shows a shrinkage of purpose - the blocking in of a door and window. The bricks are hand made and of a smaller size to suggest the early C18th. They are of a cast and hue that might define an industrial use. The window was infilled at a much later date.

The window bricks tell their story too - they look like a C20th engineering brick like an Accrington Brick. (Did you know that Accrington bricks were used as the foundation for the Empire State Building?)

This wall was pinned (possibly in the early C19th) to strengthen the structure. The render reveals, perhaps, an upgrade of purpose to something more 'polite' - perhaps a shop that sold the things that were made behind the brick wall.

The Brickworks Museum (@BrickwrksMuseum) / Twitter

From Mud to Brick – the history of brickmaking. Follow the story of how bricks became one of the UKs favourite building materials.

Can you help support my photography and writing?

Click below for membership options and benefits

Become a MemberHotspots

Barton-Upon-Humber

St. Peter - The Anglo Saxon Church

No matter how evocative the tower is at St. Peter, I think it is the simplicity of the earlier nave that appeals to me the most. However, the tower is a defining structure in the history of English architecture. It was Thomas Rickman who, in the early C19th identified the style of Anglo Saxon architecture through this church.

I've tried to work out why it appeals so much. It relates, of course, to its age, to my past obsession with Anglo-Saxons, and it has a structural 'innocence' defined by the strap work.

The history of the church is quite complex, but its form is called 'turriform' - a church with a tower-nave.

The church was closed when I visited - although the opening times stated that it should have been open. It is looked after by Historic England. This church has possibly had the most extensive investigations and archaeology than any other. Below is a plan of the burials on the circular mound - some predate the church.

The image above was taken from the wonderful HE report which is openly and freely available as a pdf download here.

Members can see a beautiful aerial video of Barton upon Humber below:

Barton-upon-Humber: the buildings

The town is well worth a stroll through. It has pockets of vernacular delight. Pantile and brick-tumbling, six-over-six sash and reticulated fanlights.

Below: this door knocker is a design 'echo' of a medieval sanctuary knocker - brought up to date with a contemporary lion's head. The little head in the door hoop is the giveaway. It perhaps represents the house behind the threshold as a sanctuary and safe place. I love how the detail reveals a story. In fact, I'm starting to wonder if that door hoop is older?

Below - the two following photos reveal the evolution of the door light, from the earliest type that has the light within the door, to the later type that has it over the door.

On Fleetgate is a building that looks like a Victorian frontage - but behind all the Dickensian bluster is a medieval building hidden in plain sight. The rear wing has an open hall built of timber.

Sustenance

Sustenance was sought at The Fig Tree cafe.

St. Mary, Barton-upon-Humber

Oh what a joy to find two ancient structures within yards of each other!

The setting is divine - next to the Humber. St. Mary's tower a beacon since medieval times. The tower of St. Peter must have been seen from the Humber Estuary by Viking invaders.

St. Mary is of Norman origin but the structure is mainly Early English. It houses a delicious interior.

Below: C13th Early English stiff leaf capitals with transitional arcade behind.

Foliate Heads

⭕️ Patrons can see a comperandum of foliate heads here.

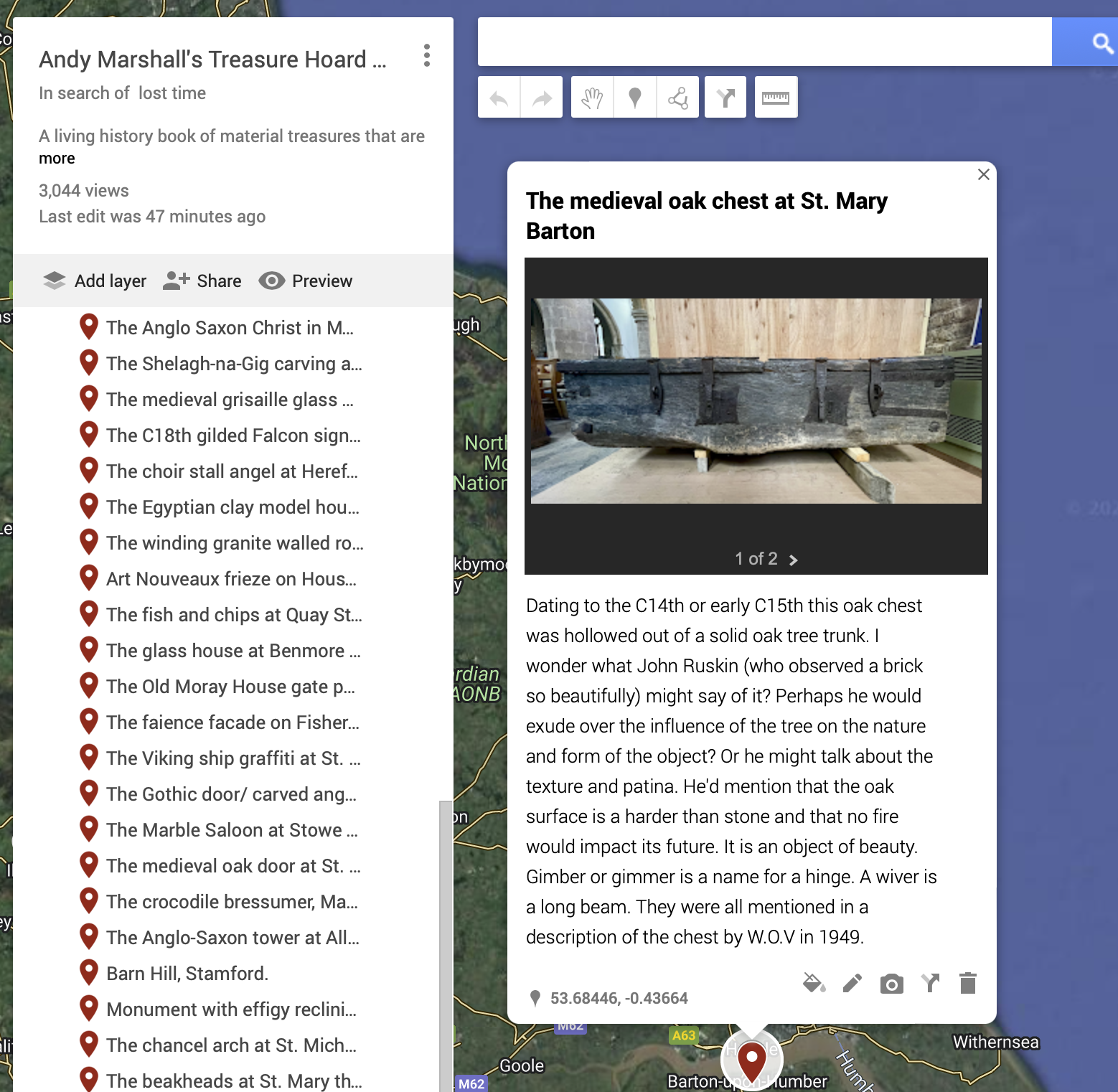

Dating to the C14th or early C15th this oak chest was hollowed out of a solid oak tree trunk. I wonder what John Ruskin (who observed a brick so beautifully) might say of it?

Perhaps he would exude over the influence of the tree on the nature and form of the object? Or he might talk about the texture and patina. He might mention that the oak surface is harder than stone and that no fire would impact its form.

Next to the chest is a typed document in a frame signed by W.O.V 1949. W.O.V lived in difficult times, probably saw bombers flying over the Humber, circling the towers of Beverley Minster (used by the Luftwaffe as a marker) and heading over to Hull to drop their bombs. Even so, W.O.V still managed to find the time to record the following:

"The Churchwardens Accounts of this Church include the following item for the year 1671-2:-

"John Winter for cutting the great chist 2 locks mending 2 new keys gimbers a stirrup for a wiver and other work 4s."

No doubt John Winter cut the lid of the chest in two, for it was too heavy for one man to lift when it was in one piece. It appears from the wording of the account that the locks, keys, gimbers, and stirrup all belonged to the chest, though they may have been connected with other work in the church. "Gimber" is a variation of the word "gimmer", meaning a hinge. A "wiver" is a long beam, usually part of a roof or other framework. If the bean in this case were connected with the chest, it was probably the bar which was once used to secure it, and the stirrup would be a staple."

This document with its inked type has become folded into the history of the church.

💫 The oak chest at St. Mary has made it to my Treasure Hoard Gazetteer. I will add the words Gimber, Gimmer, and Wiver (and W.O.V from 1949) to the Treasure Hoard Gazetteer listing - so that they will not be lost.

As if the chest is not enough, I came across another pocket font - similar to the one I came across at Waltham Abbey.

Below: the pocket font at Waltham Abbey.

As if the chest and the pocket font is not enough, I came across this delightful apotropaic mark (probably medieval).

Vanlife

After my trip to Barton I head down the A1 to decamp at a site in Cromwell in Nottinghamshire and try out my new rear awning. It's a game changer. Up and down in a matter of minutes and I can drive away from it and leave it in situ.

Next to the site is the Milestone Brewery. I head over for a glass of cider and a wood fired pizza - and to finish off a digest.

V'Envy

On My Coffee Table

Bookmarked

Victorian pumping station among 175 heritage sites deemed at risk in England | Heritage | The Guardian

Many sites have been saved but King Arthur’s Great Halls and 12th-century Malmesbury Abbey remain vulnerable

Lea Bridge library pavilion – lending new life organically to a public space | Architecture | The Guardian

The tree-friendly, timber-lined extension to the east London building is a soothing haven that works in harmony with its surroundings

Mediaeval Buildings: Hidden Historic Houses - Triskele Heritage

The second in the Triskele Heritage 2022-23 Winter Series of Lectures: Understanding Mediaeval Buildings. The vast majority of historic buildings have never been researched. Many well-known or high-status structures have not been studied in depth. There are literally thousands of mediaeval and early modern timber-framed buildings which are hidden in plain sight. This talk will

❓Do you have an event you'd like me to include here? Drop me a line.

Film and Sound

BBC Sounds

The peace and tranquillity of an ancient settlement at Harford Moor on Dartmoor.

Earworm Alert.

After seeing the sign on the Co op in Barton - I just couldn't get this song out of my head for the east of the day.

Ooh Ahh... Just A Little Bit - song and lyrics by Gina G. | Spotify

Listen to Ooh Ahh... Just A Little Bit on Spotify. Gina G. · Song · 2003.

From the Twittersphere

Go Visit Howden

Treasure Hoard Gazetteer

Andy Marshall’s Treasure Hoard Gazetteer Map

My Treasure Hoard Map is open to all. It is an evolving enterprise and I’ll be adding more entries as time passes.

View the full map on Google maps

View the full map on Google Earth (recommended)

More on the Treasure Hoard Gazetteer

Thank You

Thanks to all subscribers for your continued support

Thanks to Patrons and Members for helping keep the Genius Loci Digest free and public facing.

And Finally

It's the day after my visit to Barton-upon-Humber. I wake up in the van and can feel the warmth of the sun just risen beyond the Great North Road. I get up and stretch then light the hob and put a pot of coffee on. There's a rising sense of expectation as to the day ahead.

I'm travelling to a place that is fabled in history, a place where doors lead into the unexpected. I lie on the bed with my coffee and look up at the map on the ceiling to find my destination - but its name is lost within the folds of the map. I take it down and stroke out the creases, and as I do so, the name starts to appear from behind the wrinkle - there it is - bold and clear as the day ahead.

Lincoln.

My Linktree

Member discussion