Welcome, and thanks for coming along!

I'm an architectural photographer. I travel around Britain interacting with special places. I work from my camper van called Woody and I share my experiences via this digest.

⚡️ View the latest digest and the full archive here.

This Digest is free to subscribers and is powered by 104 Members

16 more members will enable another free photo shoot

Member Powered Photography

Scene from a Delft ceramic of 1730, Guildhall, Coventry

Give me the long, straight road before me,

__A clear, cold day with a nipping air,

Tall, bare trees to run on beside me,

__A heart that is light and free from care.

Then let me go! – I care not whither

__My feet may lead, for my spirit shall be

Free as the brook that flows to the river,

__Free as the river that flows to the sea.

Olive Runner (with thanks to John Phillips for sending it in).

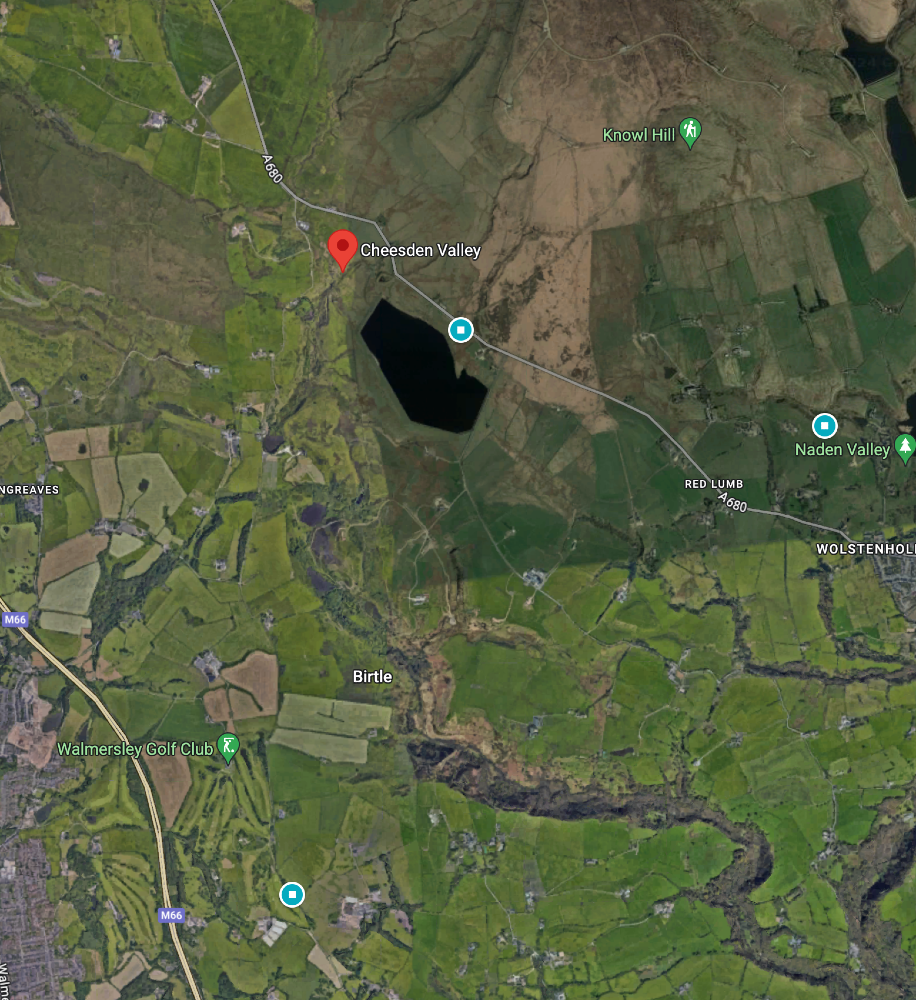

Just a couple of miles from Bury in Lancashire is a place that I’ve been exploring for over a decade: Cheesden which has often been called the hidden valley, or the forgotten valley.

It’s a deep cut thrutch, a gravelly, wooded vale of a few miles in length, embracing the industrial and agricultural remains of a generation at risk of being lost in memory.

My time there has been spent capturing and photographing the decaying constructs of working lives - the early lodges and wheel pits, the scouring becks and chimneys - suspended in a landscape more akin to agriculture than industry.

A hundred years ago, there might have been the sporadic sounds of industrial occupation devoted to the recycling of cotton. Today, the only sonic connection to textiles is the ribbon like shrill of the Curlew.

Or perhaps not.

If you listen carefully, there are nooks that still echo the sounds of people that toiled here once. They are sounds that reside within the nominology of place. It is a prose wrenched from the ice, grit and shale of the vale.

Whilst the trials and tribulations of this lost generation can be caught within the receding water-shot walls of the valley, their vibrancy and warmth is best found in the names that they have peppered the landscape with.

When I flip through the old OS maps of the valley chronologically, some of these names evaporate with the passing of time. It's a gradual dislocation of our deep-seated association with place.

The lost names tell not only of people and place, but also their interactions with it.

Birchen Bower, Birtle Dean and Blue Scar; Moulding Moss, Midge Hill and Fecit; Silen Hurst, Cinder Hill and Herculist; Cokshouse, Pigden and Bird Fields; Shepherds Hey, Deep Moss and Dunham.

The words hold within the brew: people, history, language, location and identity.

It’s a language that reflects the natural order of things.

Phonetic and poetic, the dialect rises from the nature of the land, from minds that formed a grammar of association. A lexicon which is deeply revealing of the ingress of place on person, the ingrained correspondence with landscape.

It’s a vocabulary that’s on the verge of being lost to my generation.

I come across a place called Cuckoo Narr. I ask on Twitter for the meaning of "Narr". I’m told it’s a meadow or a Germanic word for fool. But it’s only when I summon up the ghosts of my childhood, the words of my grandparents - their Lancashire twang - that I fully comprehend: Cuckoo Narr - the place ‘near’ where the cuckoo resides.

And how many generations will it take for somebody to question the meaning of the word cuckoo?

Digging deep into the words of place has given them purchase on my person. Words without meaning are brittle in my memory, but those that unravel the lives of the people that lived here before me, ignite a profoundly nourishing connection.

I'm reminded of Robert Macfarlane's words in his book The Old Ways:

'I have long been fascinated by how people understand themselves using landscape, by the topographies of self we carry within us and by the maps we make with which to navigate these interior terrains. We think in metaphors drawn from place and sometimes these metaphors do not only adorn our thought, but actively produce it. Landscape, to borrow from George Elliot's phrase, can 'enlarge the imagined range for self to move in.'

And if the kinship that rises from the phonetics of place isn’t enough, then imagine the joy brought about by the accidental discovery of the material expressions of their lives suspended in a midden - exposed by the meandering Cheesden brook.

Here I’d discovered a pattern language which embellished the places that they had named.

Can you help support my photography and writing and keep Woody on the road?

A host of juicy benefits from just £2 per month.

Become A MemberThe Midden

This is a tale conjured up by a magical quirk of nature, told by a babbling brook that skirts its way through a wooded valley, where out of the dishwater-grey water, came dishes.

The valley at Cheesden lies on the northerly edge of Greater Manchester. It’s a moorland vale flecked with industrial melancholia, host to a muddle of Georgian and Victorian mills dotted along its three mile descent into the Roch Valley.

It all began with a walk through a part of the valley called Deeply Vale. Here, a mill thrived to such an extent that, for a brief period, a terrace of houses sprang from the valley floor.

Whilst the ruins of the mill remain, the houses have gone, replaced by tussocked, tree lined lumps and bumps. Records are scant of the people that lived here, but there’s talk of a makeshift pub and a reading room lodged within a parlour.

This is a sparse place, and it takes some imagination to try and summon up the brick facades. It’s difficult to garner any vision of the warmth of the people that lived here.

Their masters are much better documented. Their stories are captured within the newspapers of the day. Their portraits hang in the galleries. They tell of fortitude and philanthropy, of civility and enlightenment.

The people from the valley were rarely recorded, their trials and tribulations only surfacing in the places they named, court records, marriage and death certificates.

My discovery was along a part of the brook that had been straight-jacketed in former times to regulate the flow of the watercourse.

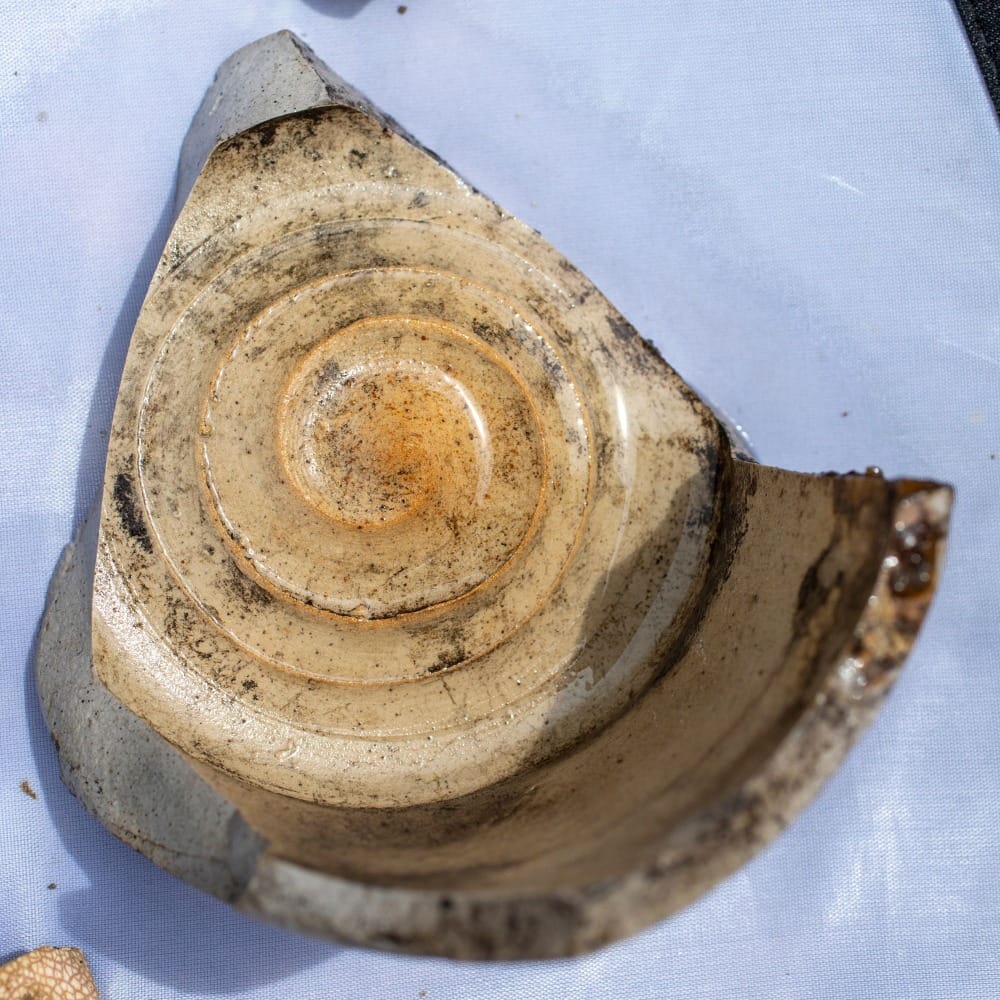

Whilst walking along the bank, I had seen chalky flecks of white. The brook had broken its course and cut into a midden, which had spouted onto a kidney shaped sandbank a scattering of fragmented pots and glass.

At a later date I returned with a camera to photograph my finds, but things had changed - the selection of ceramics on display had been refreshed. The brook, after a heavy bout of rain, had washed away the original booty and brought me new offerings.

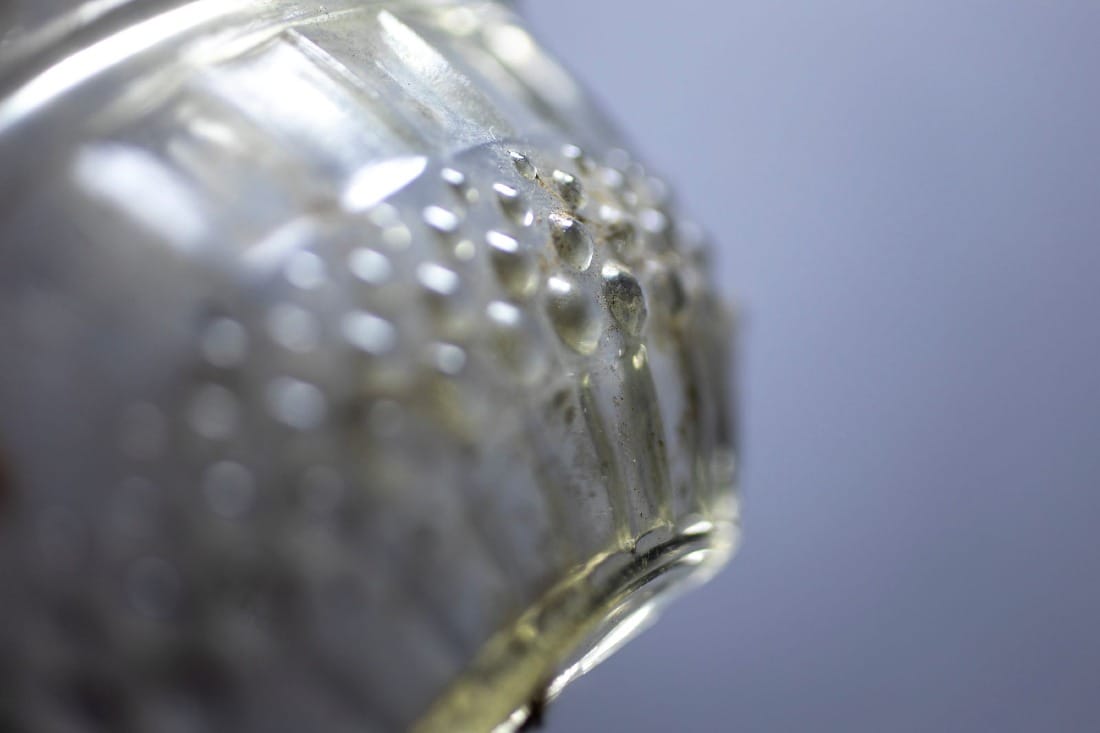

I photographed shards of floriated china, earthenware jars with truncated words and stoppered bottles with fluted sides.

The urge to pocket the artefacts was overcome by a greater want. The need to supplicate this revolving rill of water by returning the offerings, so that it might conjure up new delights.

A few weeks later I visited the brook again. The brook had been in flood and brought about a collapse of the river bank, and once again, my sacrificial offering had been supplanted by another curation of patterned bliss.

This distillery of design had infused the bank with a moonshine mix of ornament, symbol and metaphor. Tastes of former times were burnished in faience, trammeled in metal, embossed on glass.

Although the great washing of the bank made the past seem more soluble and transient, its grip on the present remained in the magical re-incarnation of tokens from lives gone by.

In certain moments, when I stepped upon the slip between earth and water, I felt washed up myself, disconnected and unplugged from the present.

And so my visits increased, and the babbling brook kept telling its story, each chapter replenished by its ebb and flow.

It told me that in this solitary place, they had hearths to go to, drank pop and beer and tea...

and washed their hair.

More visits revealed a pattern of taste spanning several decades from the Adamesque to Art Nouveau to Art Deco.

It’s times like this that offer the chance to step through the thin veil, a momentary glimpse into a hidden past.

During my last visit I took a portable box and light and photographed some of my finds with the deepest reverence for the long forgotten people of this place.

The simple act of curating the photography, placing the find, gently cleaning its surface and setting up the light let the genie out of the bottle: 'They were just like us..' , I thought.

I could see the heat of their lives beyond the robbed out walls at Deeply, burning like an embrasure in the night.

Winter in the van has been embellished by a Christmas present from my daughter, Emily - an outdoor duvet.

Em, (when she was a toddler) used to carry around her 'lellow cuddy' (yellow cover) and I spent an inordinate amount of time trying to ween her off it.

But, alas, I have been struck by 'lellow cuddy' syndrome.

I've been using the Night Lark Sherpa Fleece Outdoor Duvet (not sponsored) as a shoulder cover during the day, and as an extra blanket (tucked into my sleeping bag at night). What's great about it is that it has a fleece on one side and a water resistant material on the other. It's ingenious..

The Cheesden Valley in Winter.

We all have places that we go to when we need solace, and when I went to the Cheesden Valley a few weeks back, I filmed my journey through the snow for Digest subscribers and members.

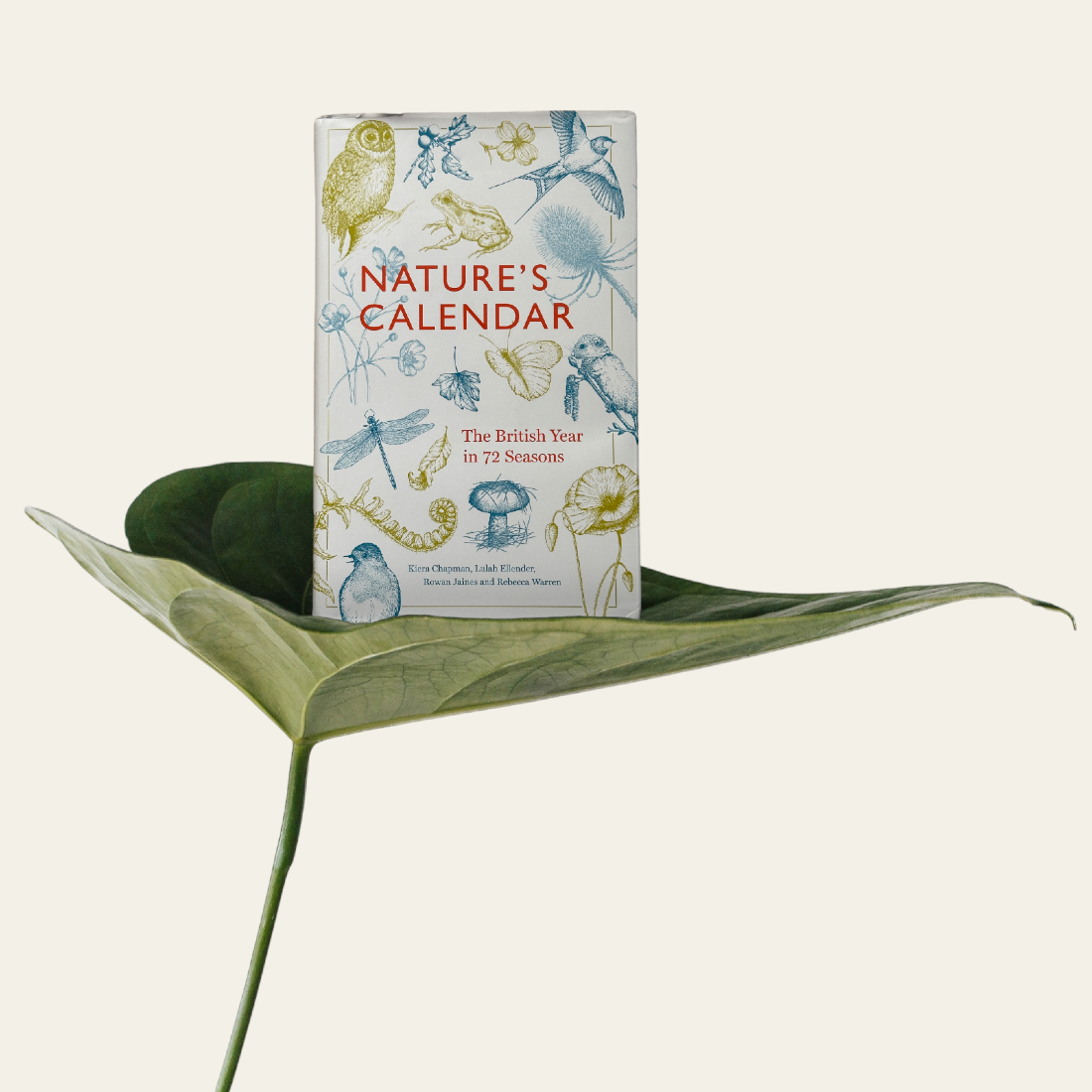

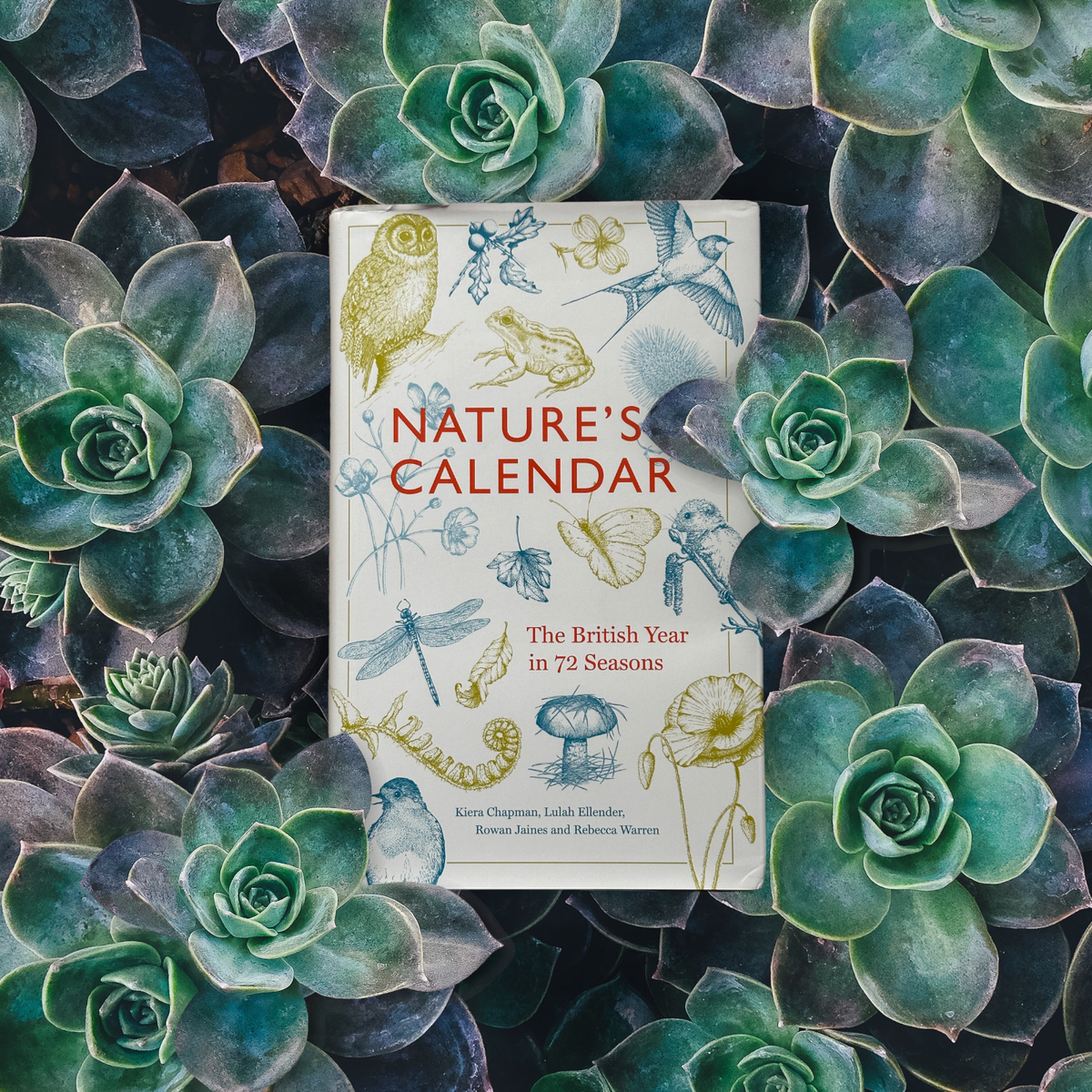

Nature's Calendar: The British Year in 72 Seasons.

Kiera Chapman, Lulah Ellender, Rowan Jaines and Rebecca Warren.

I'm sat in the van on the darkest of darkest days. On days like this the walls seem to close in and the glow of the interior light is cast in small defined circles. The heater is on, but there's a nip in the air: the side windows are frosted.

I reach for Nature's Calendar from the shelf at the back of the van and read the first passages.

Instantly, I'm transformed by a few lines that offer hope in the darkest days:

'Research undertaken at Coventry University suggests that spring moves at an average of 1.9 miles per hour across the UK...Hawthorn leaves..open first in the south-west, and the timing of their unfurling travels in a north-easterly direction at a rate of 6.3 miles per hour. Sightings of the first flutterings of orange tip butterflies travel at an average of 1.4 miles per hour...Spring is not so much an event as a movement...'

Nature's Calendar is a glorious collaboration between Kiera Chapman, Lulah Ellender, Rowan Jaines and Rebecca Warren.

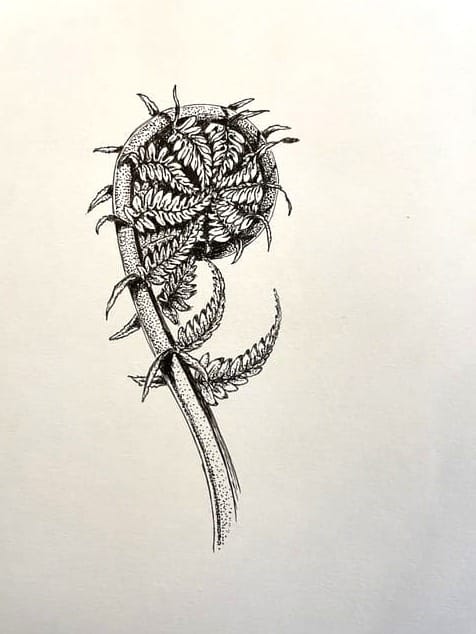

The book has been beautifully illustrated (also with some chapters written by her) by Digest subscriber and member Rebecca Warren.

Rebecca regularly keeps in touch and passes on such wisdom and support in her correspondence. She has also sketched some of the buildings from photographs in this Digest.

The book came about by chance. In Rebecca's words:

'Living in the countryside and already passionate about the nature, I met up by chance on-line with three other women who shared this passion. Confined to our homes and local areas, we shared our experiences of seeing small changes in the natural world outside our windows. When one of us mentioned the ancient Japanese tradition of dividing the year into numerous ‘micro-seasons’, rather than week or months, we began to wonder how a British Micro-Season calendar might look.'

Rebecca has kindly shared some of her original sketches from the book for digest subscribers:

If you would like to read more of Rebecca's words and see lots more of her original drawings - see here:

Updated:

More posts added to the Eustace Collection:

Foliate Comperandum has been updated with new images:

Recent Digest Sponsors:

The National Churches Trust has just launched Every Church Counts: a six point plan to save the UK’s church buildings.

We lose these places at our peril, for the answers to our plight might lie within this priceless material record. Not necessarily in providing the solutions to our problems, but in reminding us of how normal people like us relentlessly hacked, carved, forged, daubed, etched and wove our way out of the unremitting labyrinth of threats to the human condition.

We need these places now more than ever..

To find out more about the National Churches Trust Plan see here:

17.jpg?itok=iuBZL-az)

Here's why I think that our churches are so important:

People Like Us

I put my heart and soul into the Genius Loci Digest and it takes a day a week to produce. With your support, I’m able to keep this digest free and public facing. 📸🏛🚐

Sponsor a Membership and get your own landing page on the Digest

More information hereThank You!

Photographs and words by Andy Marshall (unless otherwise stated). Most photographs are taken with Iphone 14 Pro and DJI Mini 3 Pro.

Member discussion