⚡️ View the latest digest and the full archive here.

📐 My Goals ℹ️ Donations Page & Status 📸 MPP Status 🛍️Shop

✨Holiday Edition✨

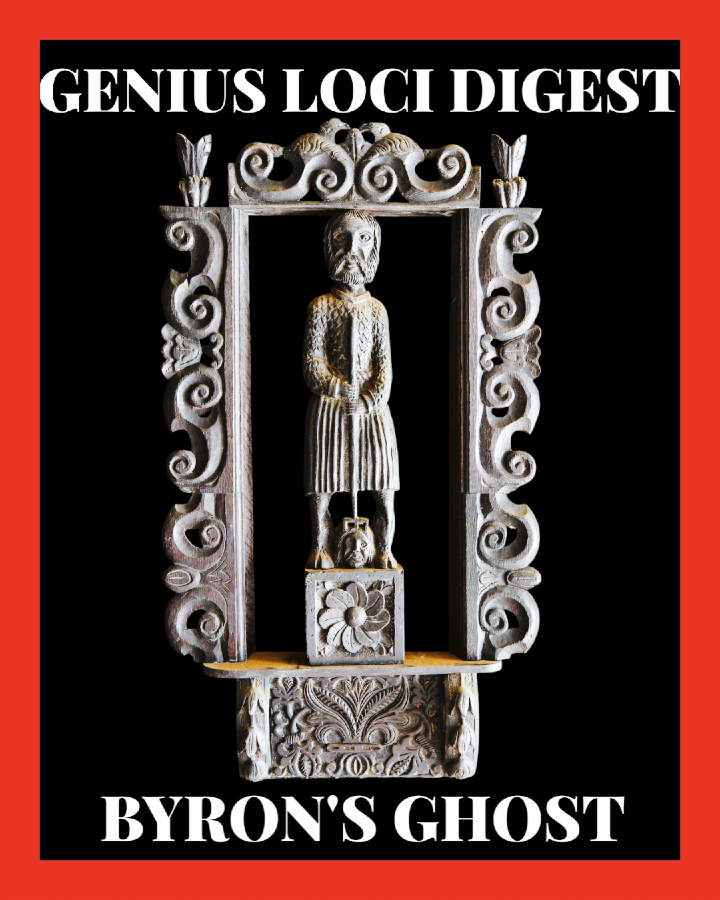

Medieval spere truss from the open hall of Hopwood Hall in Middleton, Greater Manchester.

When we lose a building, we lose a part of our everyday story; the familiar. We lose something that roots us: a connection is broken. And as that snaps, so too goes embodied energy. We mustn't save everything, but maybe we need better ways of stopping needless destruction.

@MrTimDunn on Twitter.

Preamble

I'm on a retreat this week, so I thought I would share a small part from a draft of my book called 'A Singular Point of Light'. The draft of my book is being serialised monthly with Parlour, Piano Nobile and Palazzo members.

I spent many years seeking out the constituent parts of Genius Loci. I even wrote a thesis on it. However, over the years, I've come to realise that Genius Loci only emerges through people's relationships with a place.

Keith Basso says that dwelling is said to consist in the multiple 'lived relationships' that people maintain with places, for it is solely by virtue of these relationships that space acquires meaning.

Hopwood Hall was one of the first places that revealed such correspondence through the anticipation of its loss. Here is a passage from my book about my visit to the Hall which is situated in Middleton, Greater Manchester.

A Singular Point of Light

One of the first celebrities of modern times, the poet Lord Byron had been there.

He visited the hall on the cusp of fame. According to Fiona MacCarthey Byron’s influence _‘went far beyond the literary to encompass musicians and artists. It influenced nineteenth-century portraiture and dress, attitudes to nature, scenery and travel, views of morality and human relations, becoming in itself a way of life’’.

At Hopwood, where Byron’s feet had trod, lumpy clods of plaster had fallen, making their presence known beneath my soles - prickly protestations at the status quo. During my visit, groping in the half-light, I stretched out my hands for anchorage to find them pawing at gawping faces and beheaded statues.

In the gloomiest corner my fingers padded against the bowls of carved lettering on the panelling, and as I thumbed and sounded each letter, I sensed Byron again: who, when journeying in Europe at Isola Bella, came across incised wording on a laurel tree. The word ‘Battaglia’ had been carved by Napoleon Bonaparte on the eve of the battle of Marengo.

I’d come to Hopwood in haste. It lay in an isolated hollow shrouded by a copse. I had a key from the local authority who had mothballed it because of lack of funds. It was because of looming bankruptcy that Byron had travelled north to assert his familial rights to coal mines in Lancashire and his manorial rights at Rochdale.

The occupants of Hopwood Hall, Robert and Cecelia Hopwood, took him in and entertained him for several days. His presence was vacuous. He was in a sombre mood, following the recent death of his mother.

A cousin of Cecelia Hopwood, Mary Loveday met him at Hopwood, and in her journal describes Byron as “a pale, languid looking young man who seems as if he could not walk upright from sheer weakness”. She talks of him prowling around the sitting room reading snippets of text from books. There are early indications of the ‘Byronic’ isolated tragic figure here, at odds with society and full of anxious energy. Local rumour has it that Byron made alterations to his meme of a poem, Child Harold’s Pilgrimage, at Hopwood. He’d received a proof early in September from his publisher and was to make changes to it before its publication in 1812. Might Hopwood Hall have been an inspiration or an incubator for some of his poetry? Did he revise a line or two beneath the creaking trusses of Hopwood? Whether or not, I’m tempted to think that Byron, after seeing the ancient interior might have been inspired by the weight of history within its walls.

Back in the present, the Hall was buckling under the weight of redundancy. The scene that emerged before me in the Oak Room was of dereliction and decay.

I could hear a dripping sound somewhere in the distance. Somebody had stolen the lead from the central gulley which ran like a spine across the whole building. Because of the halls isolation, water had been pouring in for some time. To make things worse, thieves had forced entry and taken carvings and statues in the panelled rooms. And what carvings they were: oak panels deep cut and floriated in a Northern Renaissance style: faces gurning, gadrooned exotic birds, and effigies arcing out as if from the prow of a ship.

In spite of that, it was to be part of the original open hall, a darkened room, that drew me away from the Oak Parlour. It was a mere rump, a truncated chamber with mullions shuttered by ply and a shattered gas fire protruding along a panelled wall.

I was summoned to this space because it reflected how I felt. I didn’t know it was there. It found me instead of me finding it. The scene before me had emerged from a deep well of sadness inside. In the shadows lay my anger and frustration at how we could cut a fragile cord that gave me access to the levelling experiences of the past. In the light was Byron, his troubled life resurrected in the brief second of a gap between passing clouds. Byron like a caged leopard - isolated and evanescent - captured fleetingly within my image.

Membership helps keep me on the road, keeps the digest alive and contributes towards Member Powered Photography - free photography for historic sites.

Here are some photographs from a visit I made to Newstead Abbey for World Monuments Fund in Nottinghamshire. Newstead Abbey was the home of Lord Byron.

I put my heart and soul into the Genius Loci Digest and it takes a day a week to produce. With your support, I’m able to keep this digest free and public facing. 📸🏛🚐

Do you know of a company or firm that might be able to sponsor the digest? Sponsorships are now going towards Member Powered Photography and recorded on the Donations Page.

Sponsor a Membership and get your own landing page on the Digest

More information here

Thank You!

Photographs and words by Andy Marshall (unless otherwise stated). Most photographs are taken with Iphone 14 Pro and DJI Mini 3 Pro.

Member discussion