Welcome!

Thanks for coming along

⚡️ View the latest digest and the full archive here.

📐 My Goals ℹ️ Donations Page & Status 📸 MPP Status 🛍️Shop

Celebrating 2000 Subscribers!

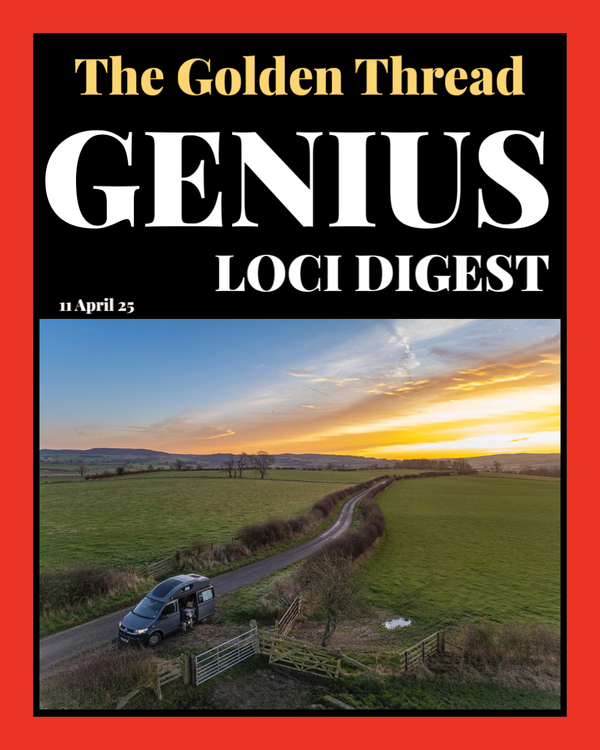

It’s been an incredible journey, a lot of hard work, and 80,000 miles in Woody to bring Genius Loci Digest to where it is today.

I’m deeply grateful for everyone’s engagement and support, especially in a thriving blogosphere where so many stories are being shared and celebrated.

Northwest Bylines recently highlighted my journey to 2,000 subscribers, a milestone made possible by this community’s connection to history, architecture, and the spirit of place. If you’d like to read more, here’s the article:

I’m delighted (and a little amazed) to share that the Genius Loci Digest has reached 2,000 subscribers.

It’s been hard but rewarding work to get here, and while I’m passionate about sharing stories of photography, architecture, heritage, and wellbeing, promoting it and connecting with the press doesn’t come naturally to me.

If any of you know editors who might resonate with this journey, I’d be so grateful for an introduction. You can find more about it in the press release below.

Thank you all for your support – it means the world to me!

John Ruskin said of Lincoln Cathedral that it is “out and out the most precious piece of architecture in the British Isles.' But it isn't just the grandiose views - the Romanesque details, like the door to the west front, are out of this world.

“The two most important days in your life are the day you are born and the day you find out why.”

Mark Twain

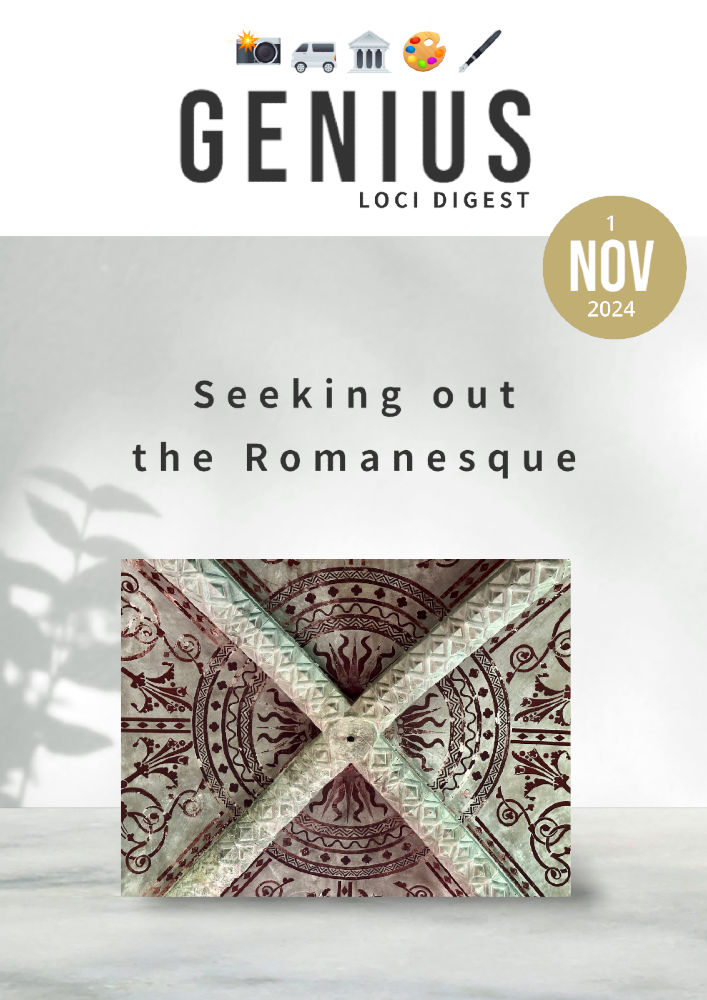

ROMANESQUE

I'm visiting an exceptionally beautiful Romanesque church in Buckinghamshire, and while I'm there, the chevrons remind me of my journey so far...

My breakdown led me back to activities from my past that I’d completely forgotten. It revived my childhood fascination with the marks, textures, and materials found in the buildings I inhabited.

As a teenager, I connected the accidental marks on the walls of my home with the activities that caused them, creating stories behind the mark-making. In a poem, I linked the death of a pet to the clawed marks on my bedroom wall:

“The whishbangwallop of the empty cocooned cat’s claw, the vibrant energy it throws, but it moves no more in its nylon carpet folds. And, if its stillness shows me the movement and how its denouement gave way to the presence of a tinkering inhabitant; then, oh the awe I feel when I glance at the wall, at the scratch marks, the blotches, the wattle daub pawing in certain patches...”

I was fascinated by the clues that could be found on surfaces and began to read incidental objects, marks, and textures like a form of braille. After my cat died, I made a mournful retreat to my bedroom and pressed my hand against the marks on the wall, as if trying to dab out the residual warmth of her presence. I had always been taught to seek things out in libraries and museums, but I soon established another way of understanding — interpreting the grammar of our accumulated graffiti.

Reading books, sketching, or writing prose didn’t satisfy my craving for knowledge. I wanted to immerse myself in the meaning of it all — not the hidden or abstract things, but the physical remnants that might still survive above ground; the human traces that offered glimmers of the past, like the indentations on my bedroom wall. It was something I discovered in my local church that helped me break through my first glass ceiling.

St. Leonard’s in Middleton, Greater Manchester, has stood at the top of a bluff since Anglo-Saxon times.

The current church is largely fifteenth and sixteenth century, but its dedication to St. Leonard hints at a deeper history, with a French origin. The cult of St. Leonard originated in southwest France during the Middle Ages and spread throughout Europe. Inside the church is a twelfth-century chevroned arch, re-set into the west end, which existed when the church was first dedicated to St. Leonard. The most prominent part of the arch is its zig-zag pattern, springing across the door opening in several courses. It was carved over eight hundred years ago with tools similar to those we use today.

As a regular visitor during school services, I found myself drawn to the arch’s pattern. It seemed out of sync with the rest of the church — deeply notched, tooth-shaped, like a dinosaur’s jaws. Even a fleeting glimpse of the chevrons triggered a surge of anxiety.

Much later, I returned to the church with my camera, as part of my journeyman therapy, to re-investigate my youthful discovery. I arrived early, set up my camera on a tripod, and framed the arch in my viewfinder, waiting for the sun to cast its light across the stone and onto the chevrons. Even though it had been years since I last visited, there was still a tension radiating from the sharp dynamics of the pattern. The time it took to capture the sweep of light across the arch heightened my awareness and the gradual interplay of light on the jagged carving eventually settled me into a receptive state. Over time, there was a coupling, an inherent sense of connection, evoked by a pattern shackled by ancient walls.

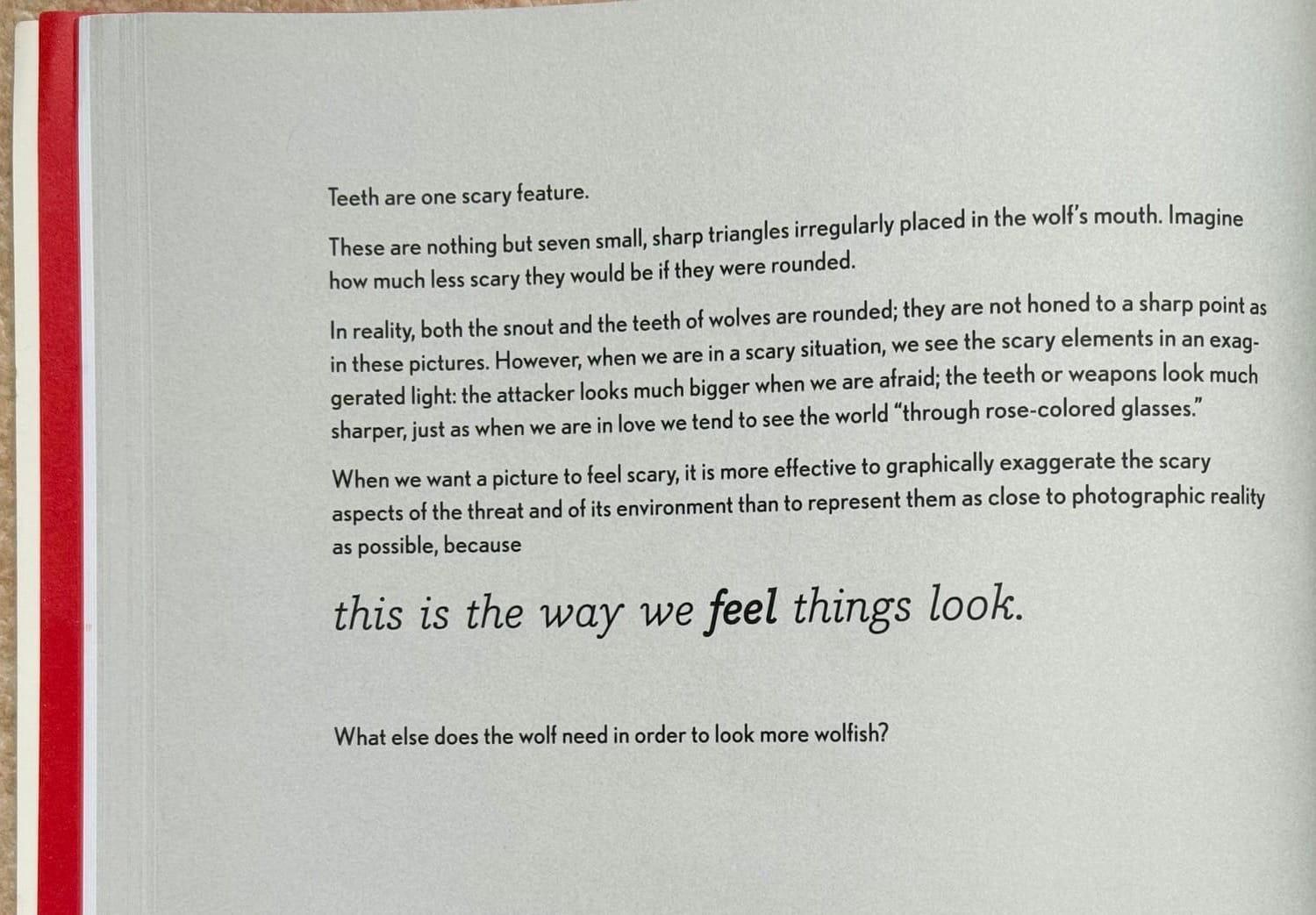

What I hadn’t known as a child was that the Normans created this style, using the chevron as a visual stamp — a cultural embossing upon churches, which were the communicative beacons of their day. I had responded to the Romanesque pattern in much the same way I might respond to a triangulated road sign, or the warning chevrons outside a school. I had uncovered a sculptural synaesthesia; a living history book recording the calcified thoughts of our Norman overlords, caught in Medusa’s gaze and frozen in stone. Its distinctive style broadcasted its autocratic intentions like a semaphore through the ether, lodging itself within my consciousness.

I saw a truth and honesty in what lay before me — more intentional than accidental, unlike the claw marks on my bedroom wall, and more vibrant than a library book coloured by subjectivity. Between observer and observed, a primary communication had taken place, a visual primer in its purest form. There was intent within these walls, and this intent not only survived beyond the lives of its makers but also brought their faded presence back to life. The carving harboured the spirit of the past; the stroke on the hammer and bolster still seemed lukewarm.

In that moment, I had the freedom to observe, to feel, to touch. Turning my back to the arch, my eyes adjusting to the gloom, I drank in the strange patterns cascading along the nave. From the spandrels in the arcade to the carved finials in the choir, the church revealed itself as a three-dimensional encyclopaedia, waiting to be deciphered.

After completing the time-lapse, I packed away my kit and stepped out into a new day, feeling a sense of renewal. My journey—from childhood fascination, through breakdown, and back to these storied walls—had brought me full circle. I had reconnected with the marks and textures that had once captivated me, but now with a deeper understanding: an appreciation of the layers of human history embedded in every scratch, every stroke, every carved chevron. The chevrons on St. Leonard's arch were no longer just symbols of anxiety or distant authority; they had become emblems of resilience, of stories carved in stone that spanned generations. By touching them, I had reached across time to the craftsmen whose intent remained alive in these enduring forms. As I walked into the sunlight, I felt a renewed curiosity—not just to read the grammar of the past, but to live fully among its presence, embracing each mark and trace as part of an ongoing narrative. My story, now unfolding, was filled with renewed perspective and purpose.

My time-lapse of St. Leonard's, Middleton including the Romanesque arch.

St. Michael and All Angels, Stewkley, Buckinghamshire.

"Rather like making patchwork, I 'sew' my daily observations into my sketchbook, stroke by stroke. I like handwork. Life becomes warm and loving because of handwork." Artist, Cai Gao

And so, many years later, I find myself in Stewkley walking through the village vernacular towards one of the most exemplar buildings of the Romanesque.

Walking into the nave feels like time travel, the view towards the altar is incised by the tower arches which are adorned with beakheads - medieval emojis - a parade of expressions that gloss the starkness of the chevrons.

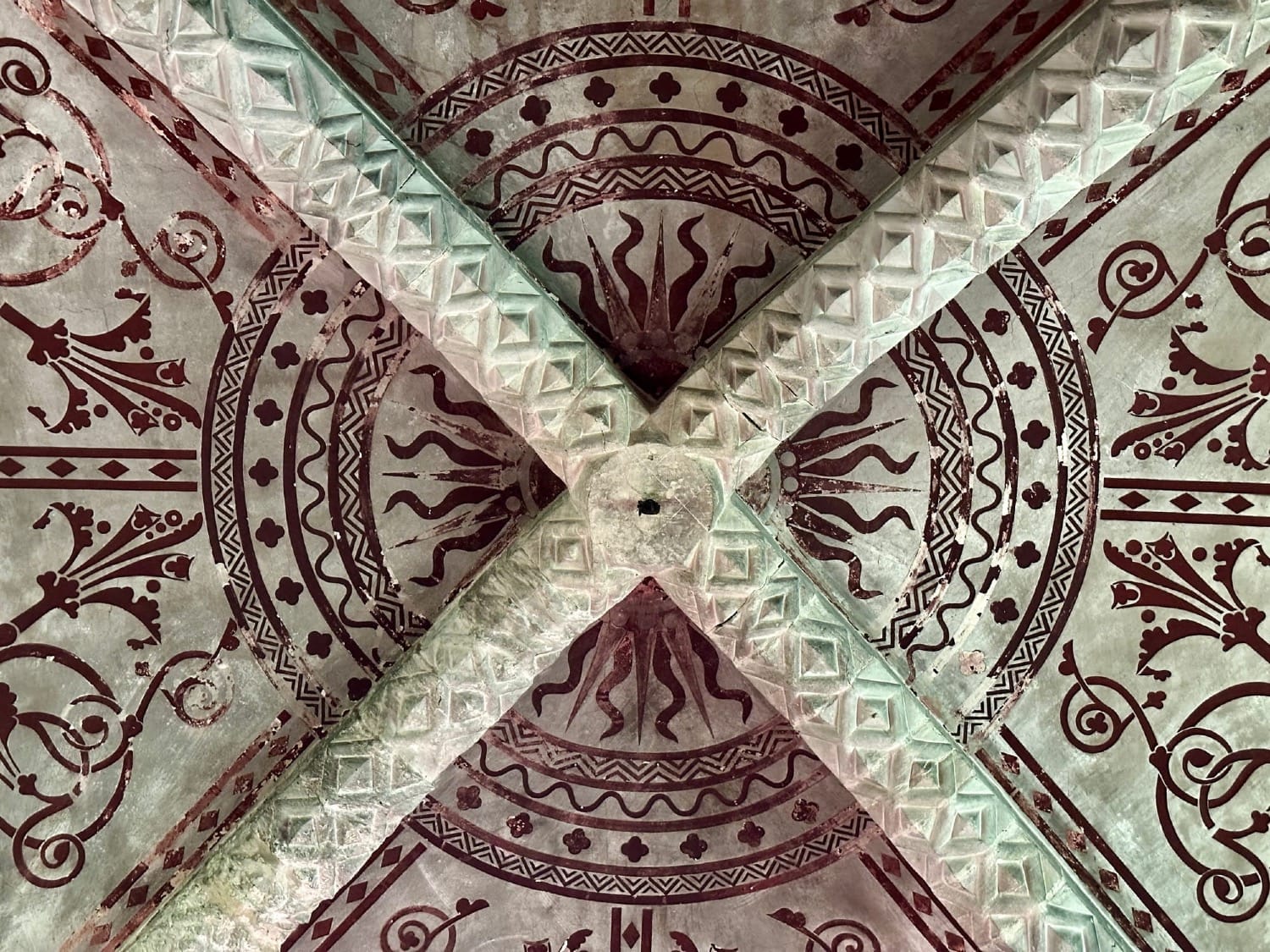

Looking up to the vaulting in the chancel reveals a Victorian interpretation of a paint scheme that might have been there originally - it gives a real jolt as to how our forebears might have experienced it.

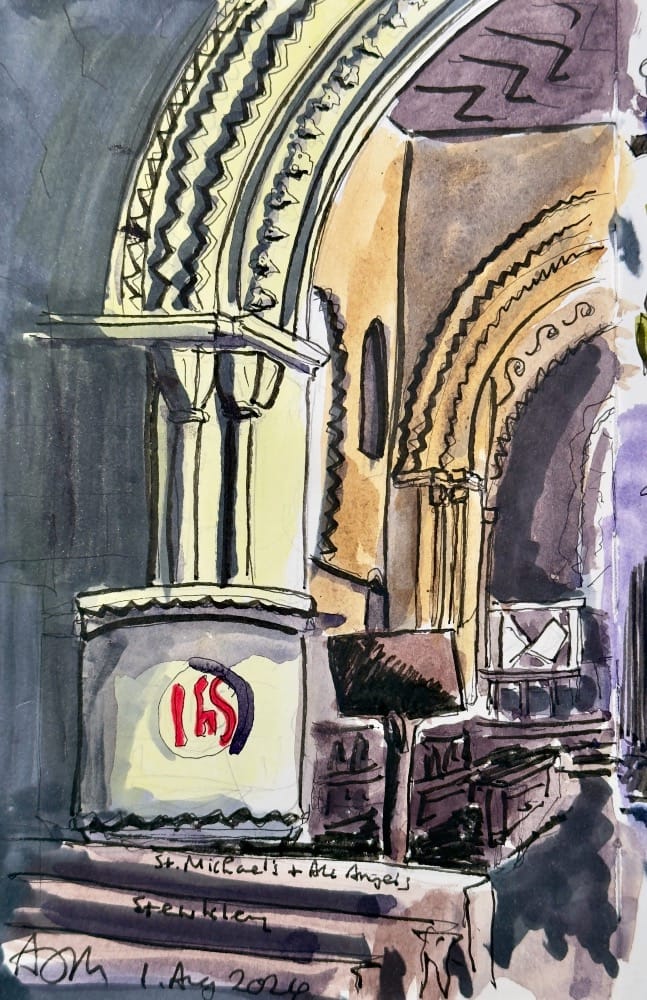

I decide to sketch the arch and set my kit up in the nave. I'm out of water but find some from the watering can for the church flowers. I think it fitting that the watercolours will be charged with water from this place.

I tear up the first sketch—another false start, tangled in overthinking the geometry. I steady my mind, recalling the day I connected with the Romanesque spirit at St. Leonard's in Middleton.

Within 20 minutes I've captured a vignette - I hardly remember doing it - mind, body and building caught in a kind of rapture. The image a thumbprint of my day.

Here, in Stewkley, it feels like the continuation of something that has been with me all along—the same curiosity that led me back to St. Leonard's with a camera, and now here, with a sketchbook.

I feel so grateful to be here, for the quiet lessons that places like this teach us. To sit in front of this arch and sketch, to capture even a hint of its spirit, is to feel like part of something bigger. .

And in that thought, I find myself feeling more settled, more rooted, as if the zig-zagging lines I’m sketching have mapped a journey of enlightenment that, for now, has brought me exactly where I need to be.

Members can see a fab aerial video of the church at Stewkley and also the interior in glorious VR (viewable on any device):

📸🏛🚐🎨🖋️

Can you help support my discoveries and keep Woody on the road in return for exclusive content and an enhanced Digest?

I lodged over in Moreton-in-Marsh

Where I made one of my regular visits to the delightful Otis & Belle

Evocation of Place - on photographing Edgar Wood: 'His Exedra is the perfect example – instead of being a destination in itself – it leads the eye to the medieval St. Leonards. It contributes to a visual hierarchy.'

At Kilpeck: "That such an exotic thing with Angkor Watt curves can be hidden within the ballast of a grim winter's day is quite remarkable."

Recent Digest Sponsors:

DONATIONS - ONE NEW MEMBER POWERED PHOTO SHOOT AVAILABLE.

As another way of enabling support for Member Powered Photography. I am putting any donations and any funds from sales of my art work, towards free photography for historic sites that might not be able to afford a professional photographer.

Thanks to you all (and some sales of my art work) I have reached the first goal and there is an MPP shoot available.

You can see the status of Donations towards MPP here:

Atelier - My Art Shop

Visit My Art Shop

Do you know of a company or firm that might be able to sponsor the digest? Sponsorships are now going towards Member Powered Photography and recorded on the Donations Page.

Sponsor a Membership and get your own landing page on the Digest

More information here

Thank You!

Photographs and words by Andy Marshall (unless otherwise stated). Most photographs are taken with Iphone 14 Pro and DJI Mini 3 Pro.

Member discussion