Compact Edition

Thanks for coming along

⚡️ View the latest digest and the full archive here.

📐 My Goals ℹ️ Donations Page & Status 📸 MPP Status 🛍️Shop

Continuing from last week's Digest, where I had a bit of a wobble on the steps of the Saxon crypt at St Wystan's, Repton, before being invited to the Communion service in the nave.

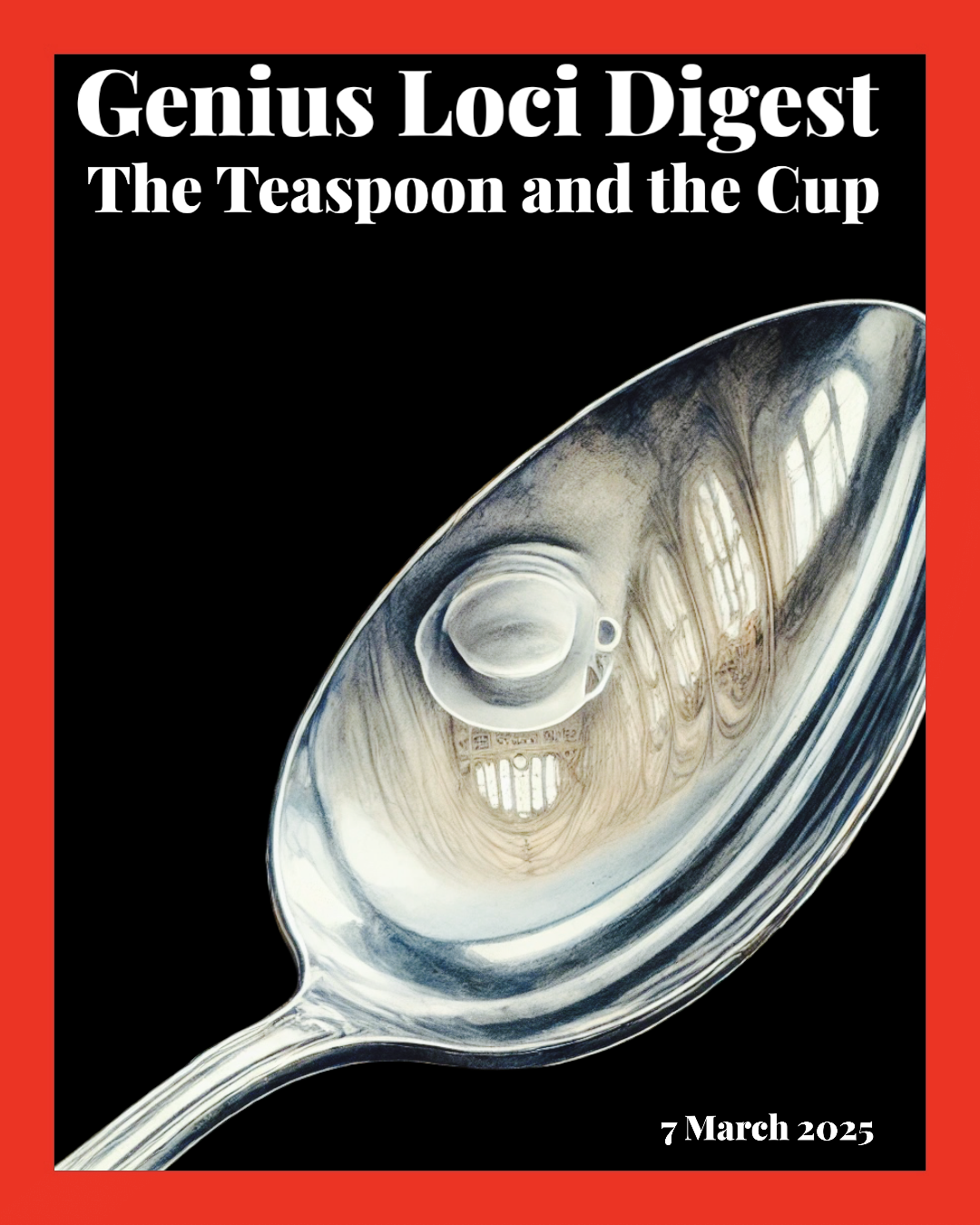

The Teaspoon and the Cup.

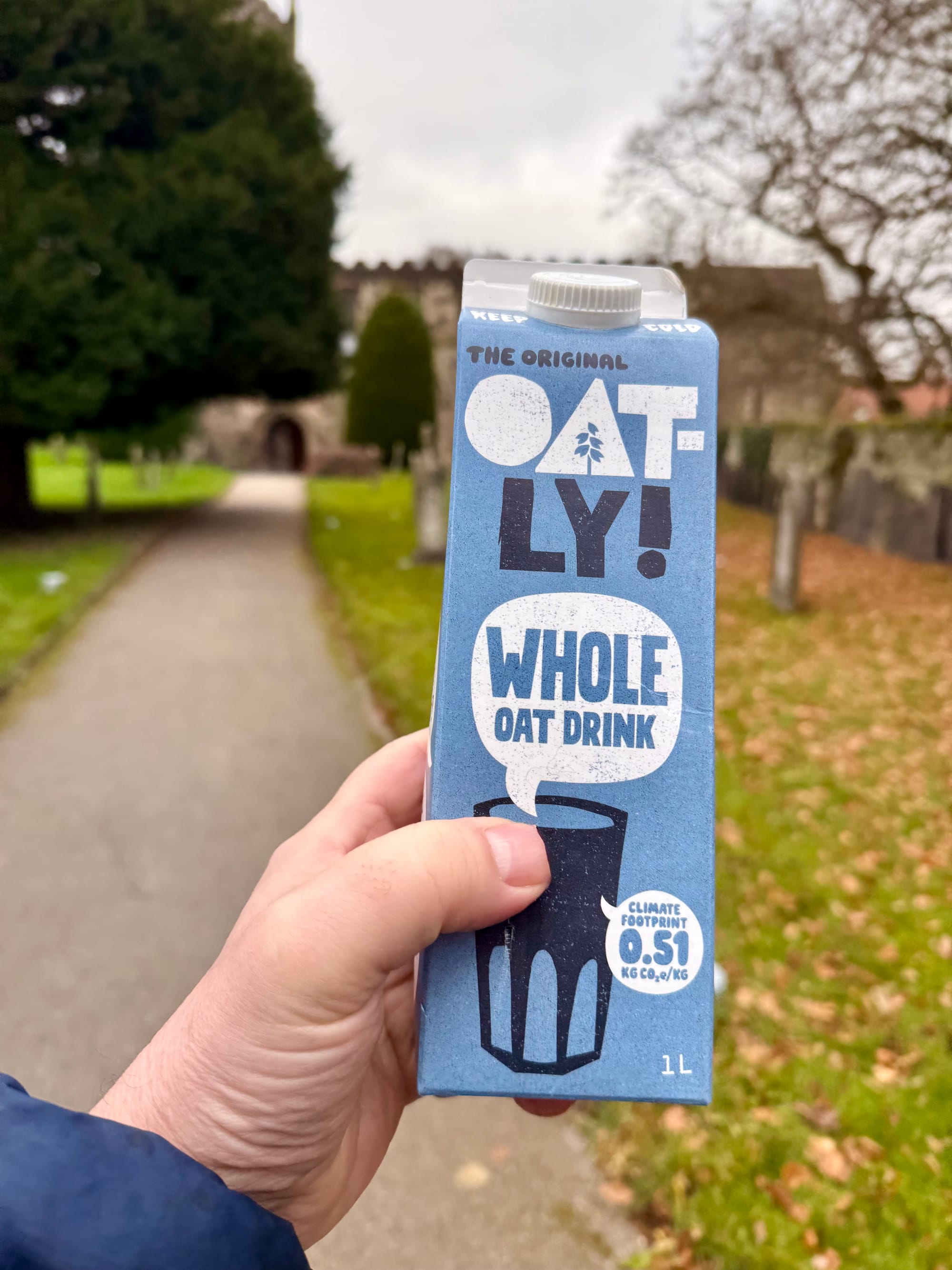

After communion is over, I’m invited to stay behind for a biscuit and a cup of tea. But there is a mild panic - they have run out of milk. I have some oat milk in my fridge, I say. I explain that I have a fridge in my camper. Milk emergency over, a small retinue from communion sits around a table with tea and biscuits at the west end of the nave.

It might seem a little odd to focus on such a simple activity, but over the years of my camper-van-camino, simple gatherings like this have been some of the best moments - times of correspondence between others in a safe and welcoming space. This is my kind of communion; the tea is incense, the biscuits a reliquary. There is something about the cadence of voices, the way one person picks up a thread where another leaves off, the chink of a spoon in a cup, the guilty rustle of a biscuit wrapper. It’s something and nothing. A small world within a larger one.

I know it’s quite rare these days for many of us. But in an era of virtual meetings, to sit with others - especially strangers - after coming together without a purpose, is remarkably uplifting. I’m convinced that, as human beings, we have a third sense - because I can feel something here that equates to a communal glue. A hint of collective emotion that orchestrates a feeling of warmth, comfort, safety - a bonhomie.

Tea, biscuits and good company are the tonic I need after the rawness of my thoughts on the crypt steps. As the conversation takes hold I start to relax, and take in my surroundings. I catch the reflection in the back of the teaspoon next to my cup - it’s acting like a fisheye lens, the whole world contained within it. I think of John Donne’s poem ‘The Flea,’ where he tries to woo his lover by stating that the flea, having bitten them both, is a marker of their world because it contains their mingled blood.

I change the wording a touch:

‘Mark but this spoon, for in this spoon our worlds mingled be.’

It feels like a comfort to see the world like that - with defined boundaries - all contained within. The same feeling, perhaps, as a cosmonaut when they look at the speck of earth through their oculus.

Then I notice the arc of the nave in the reflection.

I move my eyes from the polished echo of the world in miniature over to where the crypt lies at the end of the nave, and then up to the sconces beneath the capitals.

Then I follow the Gothic lines towards the oaken roof with its dentilled beams and floriated bosses. Upwards, through the Scottish boarding and then beyond. I think of the depth of this place, anchored by the Saxon crypt and exonerated by the pinnacle of a spire. From up there, cut away the roof, and I must look like Donne’s flea.

Outside the church, from the cosmonaut's view, the world tilts. The sky opens, and there’s another shift in perspective. The body of the church dissolves into its setting, revealing a patchwork flood plain with fluted fields stretching out. From here, the hedgerows look like the seams of an old garment.

Amidst the medieval ridge and furrow are lumps and bumps that mark events from the past, reverberating through this place. It was at Repton that a great Viking army wintered in 873 AD under the leadership of Ivar the Boneless. The lumps and bumps are the boundaries of their camp.

Follow the axis of the river back to the church, and beneath the neatly clipped grass of the vicarage garden is a mass grave, an ossuary of bones, the remains of over 250 people from the Viking army.

The skeletons of four children found nearby may have been a sacrifice to the memory of those lost in battle. Outside, to the east of the crypt they found two bodies intertwined - the thinking is father and son. The elder had a cut to his femur that indicates he lost his manhood in battle. The theory is strengthened by the discovery of a boar’s tusk placed between his legs - his virility restored before passing into the hall of Valhalla.

Just metres from their remains - earlier in the day - I had been sitting on the steps of the crypt, caught off guard by a fleeting wave of fear. But back in the church, chatting over tea and biscuits, the feeling dissipates.

Before I left the crypt, as I gathered my things, my sketchbook slipped from my hands. Its four metres of concertina pages fell upon the worn flagstones and, like me, unravelled. As the pages stretched out, I caught glimpses of the places I had visited over the last few months—pigmented hints of the continuum. A time-scape of ink and watercolour, bound together yet momentarily uncoiled. When I folded the paper back into the book, the whole four metres—all that time, all those buildings and all those memories—fitted into a sketchbook just an inch wide.

In that moment, I was reminded of some words by the actor Meryl Streep:

"I have a belief, I guess, in the power of the aggregate human attempt – the best of ourselves. In love and hope and optimism – you know, the magic things that seem inexplicable. Why we are the way we are. I do have a sense of trying to make things better. Where does that come from?"

For me it comes from the material culture of the past. The buildings and places that I visit are like my sketchbook. They hold the memory of centuries, compressed into the stillness of the present. The nutrients of the past are gathered in here, waiting to be unfurled into lessons learnt.

In a world of smoke and mirrors, there is a deeply satiating truth in what we can touch and feel before us - in a material culture that is not vocal, that passes no judgement. Yet, through what it represents, it speaks volumes about the overwhelming, aggregate human attempt of generations who, in spite of themselves, have succeeded in finding ways to live with one another. And in a world that is pivoting away from that idea, to see, in a small gathering of people, the sum of the parts of our existence laid out across millennia - like the pages of my sketchbook on the Saxon floor—is a deeply comforting thing.

Members can see a VR aerial view of Repton and the church, including the remarkable landscape around it here:

Can you help support my journey into place and keep me on the road?

If you’ve enjoyed this journey through time, tracing echoes of the past in timber and stone, I’d love for you to join me on more. My Genius Loci Digest is a labour of love—free to all, but powered by its Members.

Can you help support me and keep Woody on the road?

Lots of Member Benefits from £2 pm

Become a Member

Atelier - My Art Shop

Visit My Art Shop

Do you know of a company or firm that might be able to sponsor the digest? Sponsorships are now going towards Member Powered Photography and recorded on the Donations Page.

Sponsor a Membership and get your own landing page on the Digest

More information here

Thank You!

Photographs and words by Andy Marshall (unless otherwise stated). Most photographs are taken with Iphone 14 Pro and DJI Mini 3 Pro.

Member discussion