This article is a part of the Eustace collection - aimed at helping others create counter-narratives to threats to our historic environment.

Learn more about EustaceAccess all the Eustace articles here:

Doing the Lingua Loca

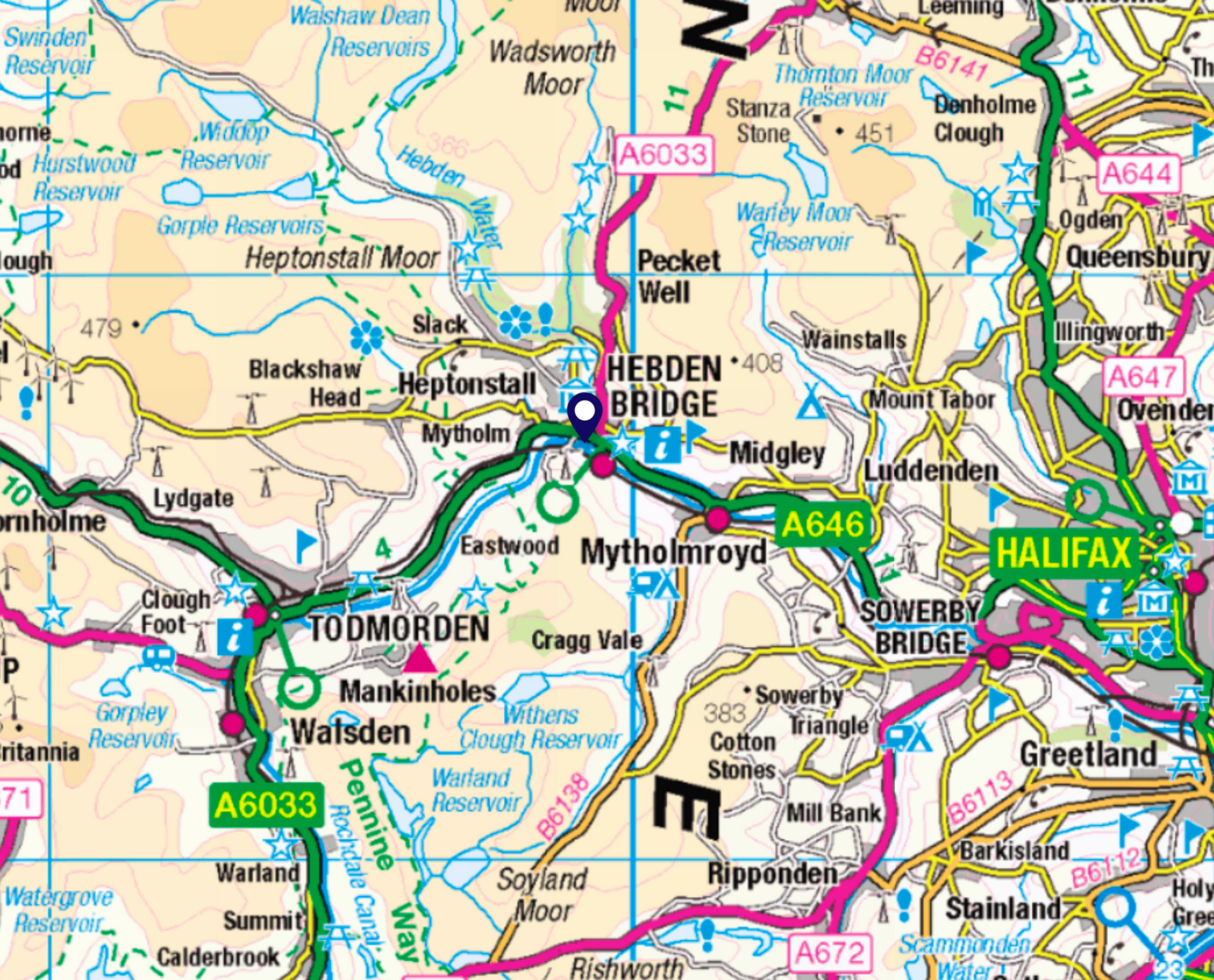

Hebden Bridge sits in the Upper Calder Valley, West Yorkshire, around the unorthodox twists and turns of the Rochdale Canal. Together, the moorlands of Heptonstall, Wadsworth and Warley form a trefoil of solitude that lies to the north. Hebden wears it like a bonnet.

I was brought up not far from this humble little town and every time I visited, I felt as though I was entering a different world. Its distinctiveness lies in the thick set and low slung vernacular, its deep cut valleys and slender peaks. It was in the corrugated folds of these parts that the Brigantes hid from their Roman pursuers.

What strikes me most about Hebden and the surrounding landscape (and it’s taken me a long time to realise this) is a remarkable survival: it is still tightly chamfered into the language of place. It’s a survival that is just as important as any archaeological find, a kind of lingua loca.

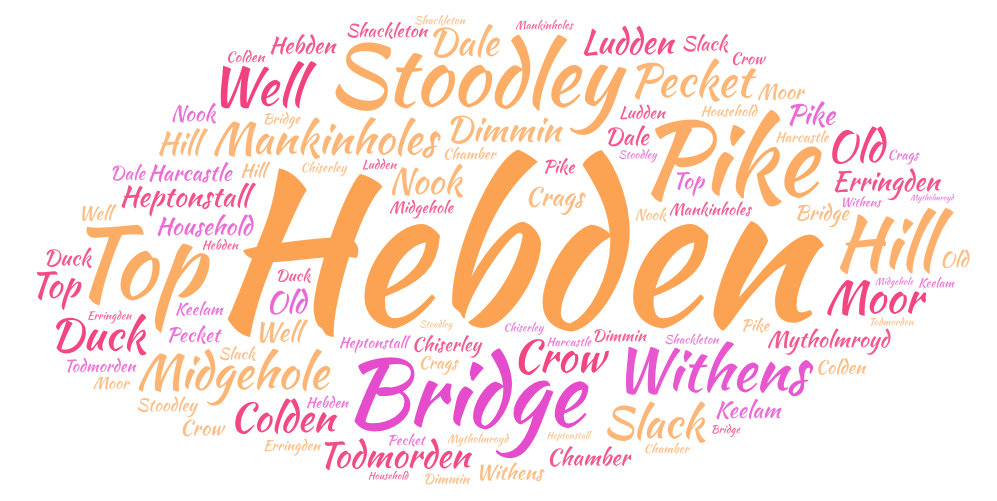

Look at any map of the Upper Calder Valley and you will see what I mean, with names abundant in the semantics of the landscape: Mankinholes, Midgehole, Top Withens, Crow Hill Nook, Slack, Ludden, Stoodley Pike, Mytholmroyd, Dimmin Dale and Pecket Well.

My grandad used to pass on tales about these places and especially about his home at Stakehill where he lived. He couldn’t read, so he was literate in the role place had in his life, and lyrical in the conveyancing of it. I didn’t realise it at the time, but his incessant regaling of the stories over and over again wasn’t an act of forgetfulness - it was an act that reaches back to our indigenous roots.

For him, place names were mnemonic - ‘place holders’ in a network of stories that held meaning for him and passed on wisdom to his grandson. In effect, they were powerful data holders, memory banks and morality codes. Place was understood through language and language was deeply rooted in human emotion.

Indigenous Australians stitched together their songlines with place names that were tied into the landscape. They still believe that an unsung land will die.

Flatten and numb a landscape by removing its associations and they will prospect it for oil. Language is a potent badge of identity and a votive agent in protecting place.

"They still believe that an unsung land will die."

I’ve been involved in many projects by providing a photographic record of buildings listed for demolition - the loss of which - has been regretted with hindsight. Their demise started with a change of use and then a dislocation from their names. On other occasions their isolation was increased by introducing new place names that had no connection to the place or relevance to the community, thus removing the nominal ring of protection.

And there is a remarkable reciprocal effect. Places that are rich in semantics are fertile ground for reinforcing community and helping it navigate the present.

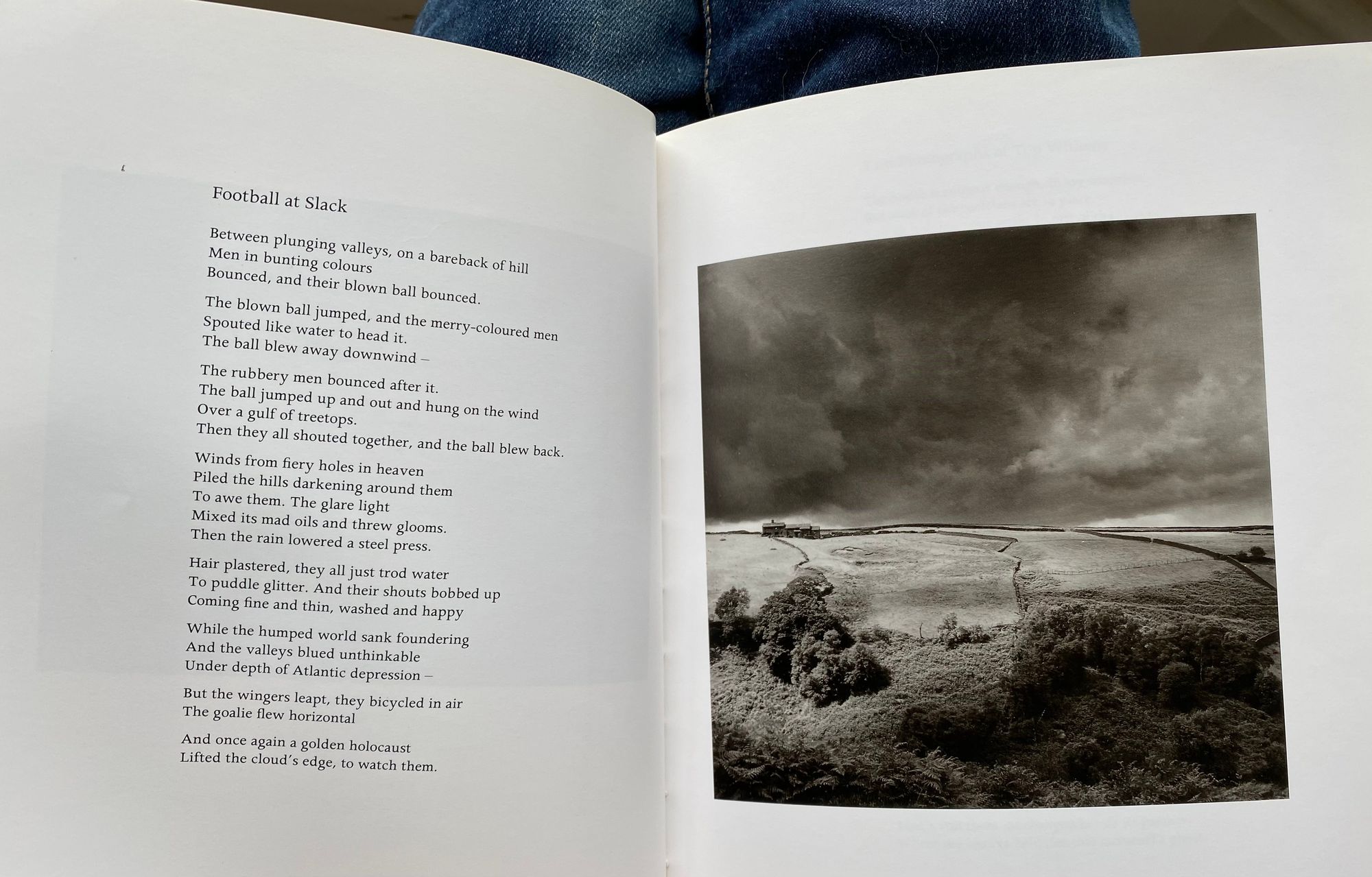

Every now and then, there emerges out of a lush lexicon, a person whose words are tugged up from the landscape around them. Ted Hughes was born in Mytholmroyd and his poems about his locale immerse the reader in a syntax that is so sensory that they are transcendental.

Ted Hughes' Football at Slack is a potent example of how the semantics of place can imbibe us:

Winds from fiery holes in heaven

Piled the hills darkening around them

To awe them. The glare light

Mixed its mad oils and threw glooms.

Then the rain lowered a steel press.

Hebden resident, Horatio Clare’s Winter Journal draws its eloquence from Stoodley Pike and gives us a much calmer perspective:

“We glimpsed a burning silver disc of sun, and then quickly, so quickly, the sky paled and blued, and air absent of mist grew like lakes in the distance. Now another bluff appeared three miles away, and now another a mile beyond that, and sun and mist and the noses of the moors swam together, shoaling and clearing as if a pod of orcas were surfacing in an Arctic bay.”

Photographs and words by Andy Marshall (unless otherwise stated). Most photographs are taken with Iphone 14 Pro and DJI Mini 3 Pro.

Member discussion