This article is a part of the Eustace collection - aimed at helping others create counter-narratives to threats to our historic environment.

Learn more about Eustace

Pie and Pudding People.

I’m back over in Ashwell, lodging in the van, and I’ve made a huge mistake. Last night was wet and warm and I fell asleep (with a book on my chest and my glasses on) under an opportune blanket that I took from the chair opposite.

At first light, I wake with a shudder - it’s freezing cold. I fumble for my glasses and find them on the floor beneath Laura Cumming’s Thunderclap.

I brave the cold and switch the heating on - but it barely registers. If heat were light on this new day, it would present itself as a tiny spotlight in the centre of the van.

I feel lonely this morning, I felt lonely last night. On the dark nights the walls of the van close in.

I decide to forego breakfast in the van and seek out warmth and humanity in Ashwell. There is a bakery that opens at 7am and I’m set on being there as it opens. I step out of the tungsten interior of the van into the blue of twilight and walk through the grounds of the campsite. I’m exhaling swags of guilloche.

I head up Lucas Lane and onto High Street. I walk with a cadence that pulls the street up by my side. I pass elbowed joints of timber and pargeted facades. The buildings rise up out of the darkness and then dissipate.

Then I spot the bakery: a warm glow spilling out onto the street. If hope were light on this new day, it would present itself as a tiny spotlight in the centre of my heart. It’s not only nourishment I need but human connection.

I look through the bakery window and can see movement. The occupants are chatting along whilst busying themselves at their work.

I walk into a warm welcome. We pass the time of day and then I make my order. I don’t really want to leave, so I orchestrate a measured syncopation between the sweet and the savoury and buy more things than I need.

The bakery is more than the sum of its parts: the people, the building, the warmth, the baked goods and the craft. This building is as much a respite as it is a bakery, as much a mental space than physical. Pies and puddings sum up the warm spirit of this place as well as its contents.

I take my breakfast through the lychgate and into the churchyard.

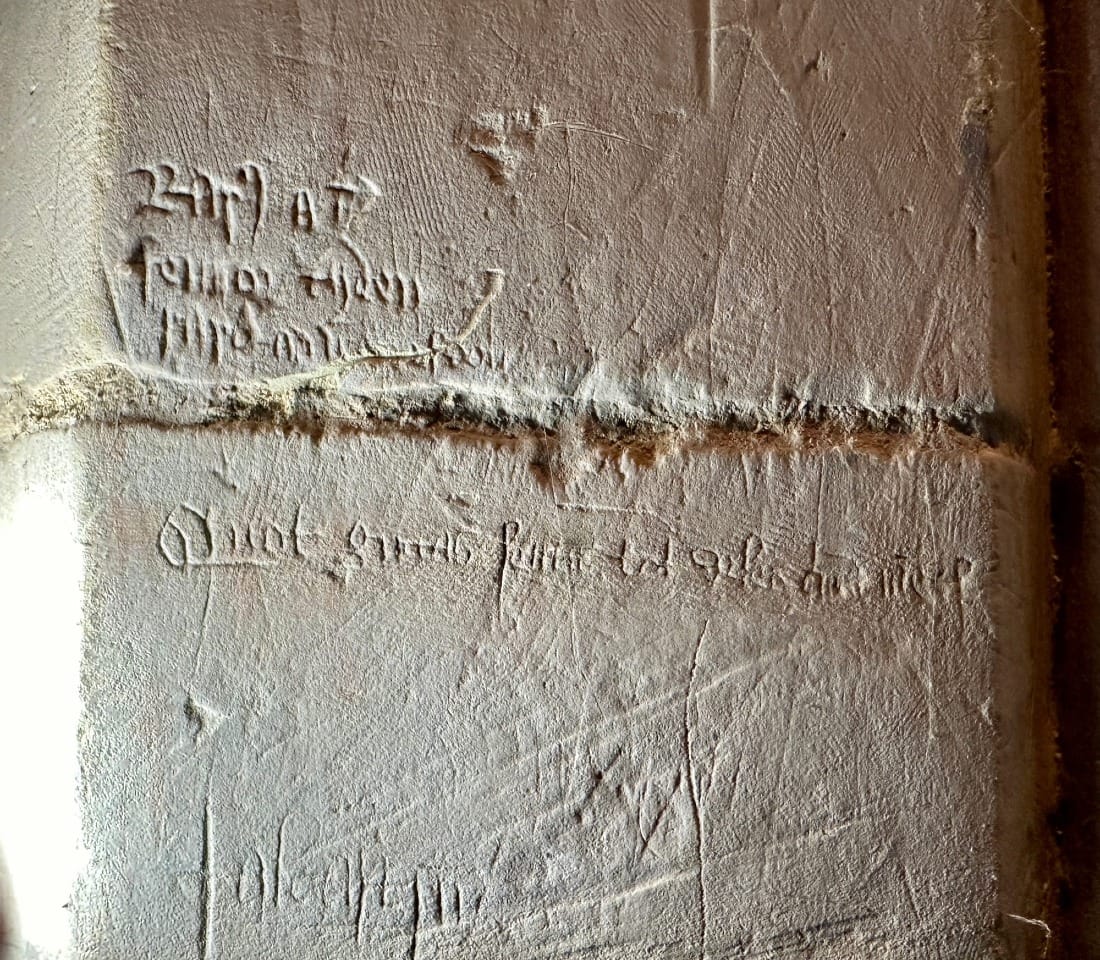

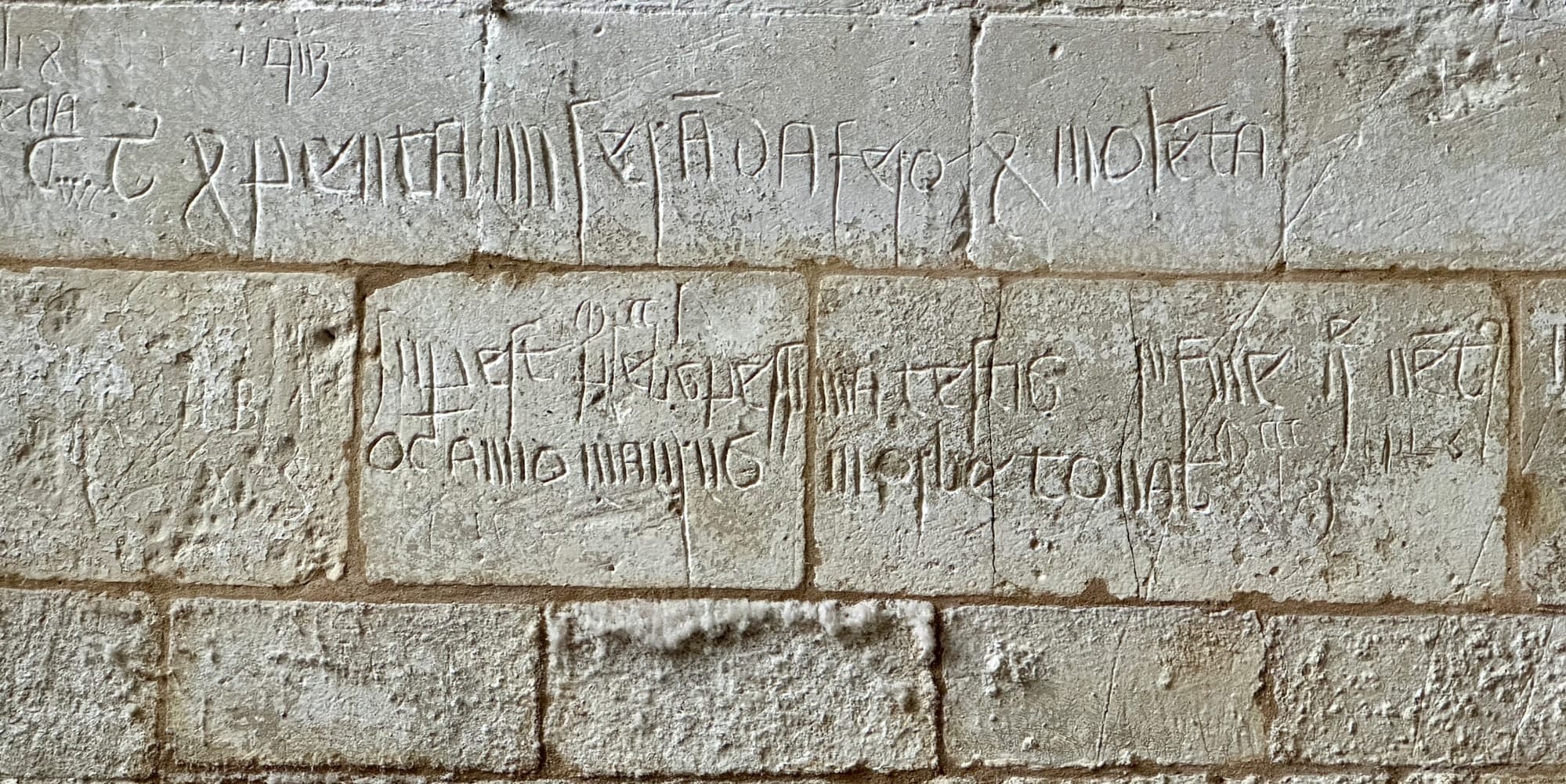

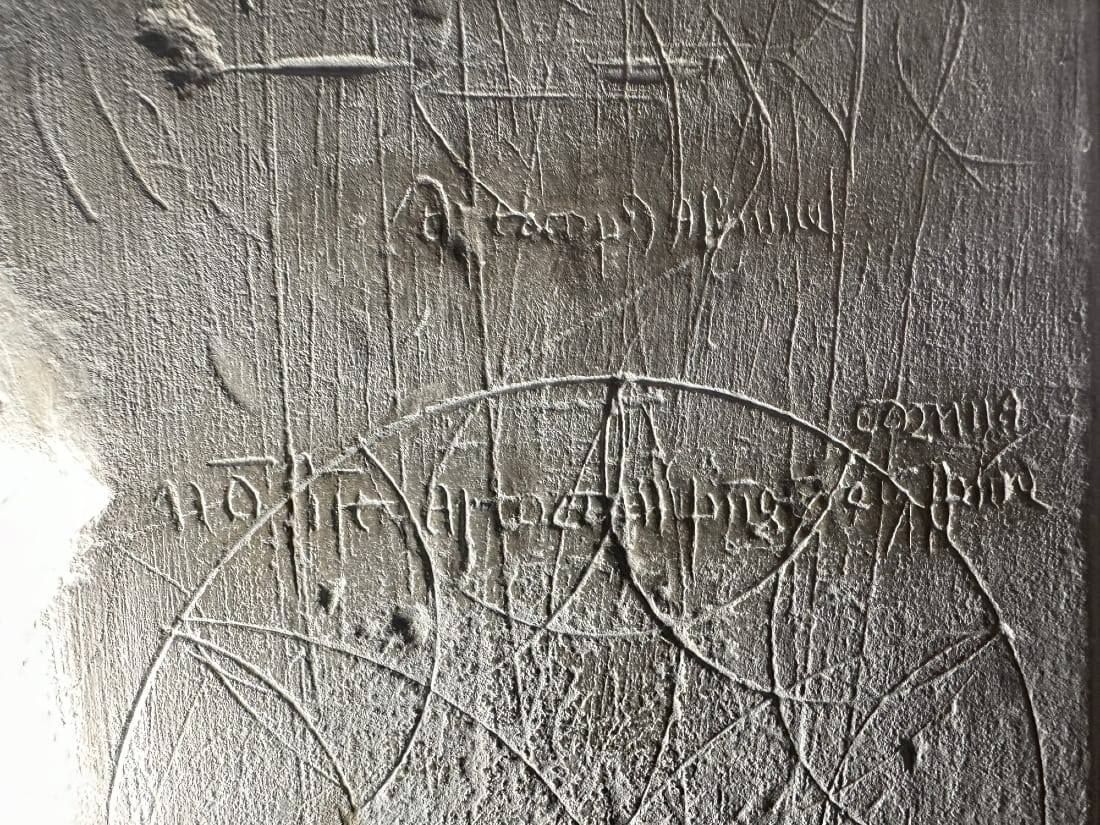

Later, I enter the church of St. Mary looking for more companionship, but it’s empty. The nave is voluminous, cathedral like and I feel small within its embrace, until something catches my eye: deep cut marks upon a column in the arcade. I can see hatchings and symbols and what looks like Gothic script.

I pick up a pamphlet which takes me into the church tower. I look up at the north wall and suddenly I don’t feel so lonely. It’s full of writing from the people of the past.

It tells us that people found respite here during the plague:

‘In 1349 there was a plague and (in 13)50’

It speaks of loss:

‘On the first day of June now with these worms he rests.’

And like us, in spite of hardship, it mentions the weather:

‘…a pitiable, fierce violent (plague departed); a wretched populace survives to witness (to the plague) and in the end a mighty wind, Maurus, thunders in this year in the world, 1361’

And then, in a way that is typically human, it takes us from the depths of despair to the sublime: a remarkable depiction of old St. Paul’s Cathedral - the cathedral that existed before the great fire.

The sketch shows the building in a flattened perspective, including the rose window, tracery, buttresses and roof (and another church with a spire to the left). Dated to the late C14th or early C15th, the artist who made this grew out of the despair that plagued this place and thought to rise above it.

And then, from the sublime to the ridiculous, I come across a faint script beneath some hash marks:

‘..cornua non sunt arto compungente Sputuo..’

When I read the translation in the pamphlet I’m filled with a telling recognition - a spark and a jolt between people separated by millennia. It’s a commentary on the building:

‘These corners are not straight, I spit.'

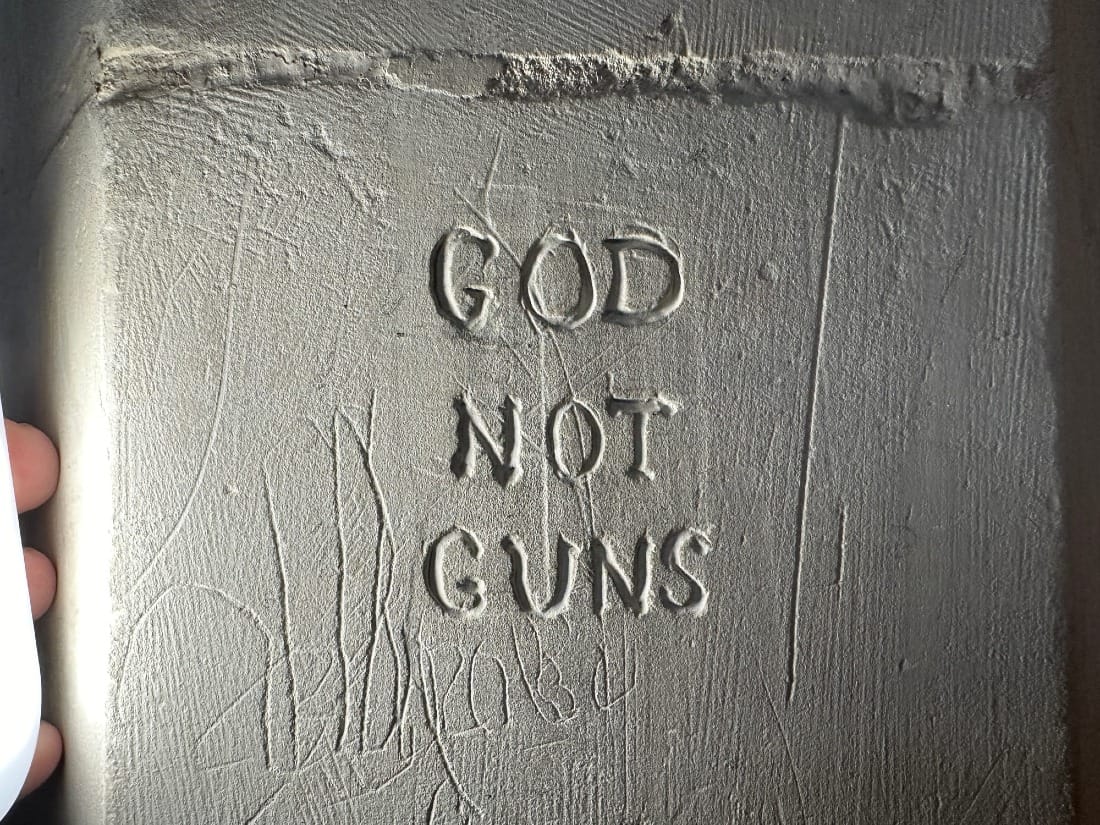

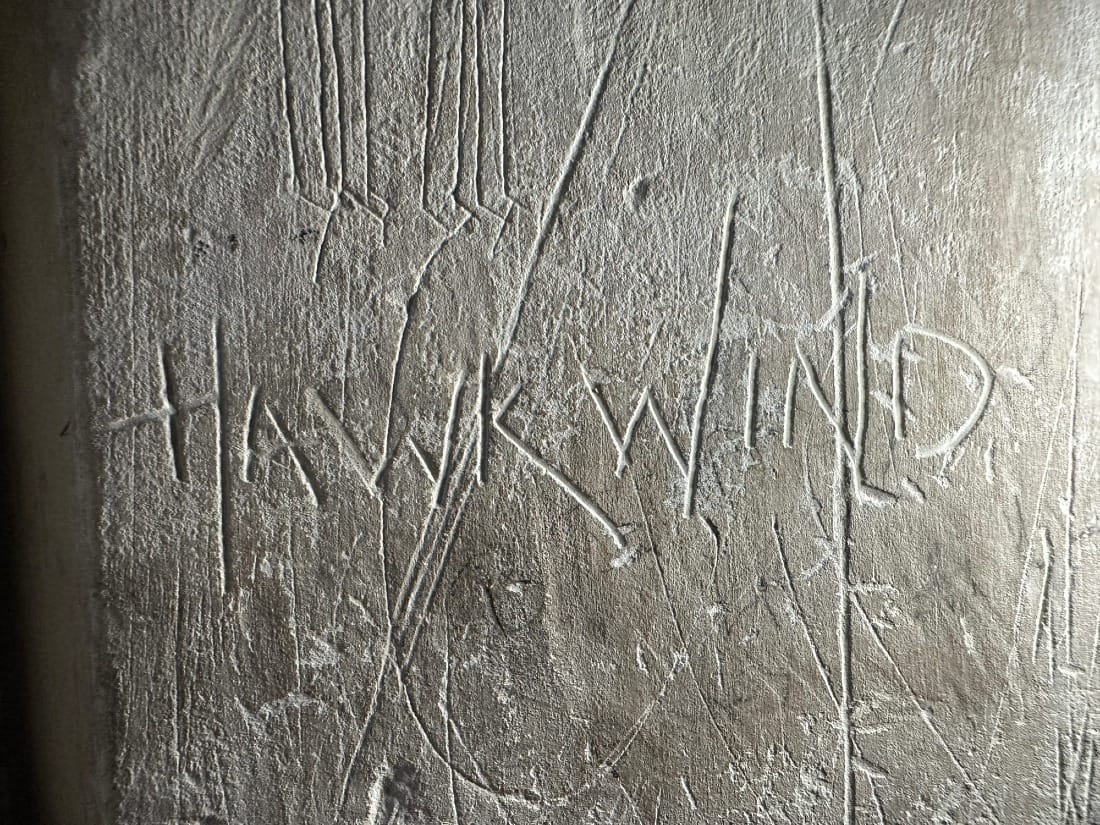

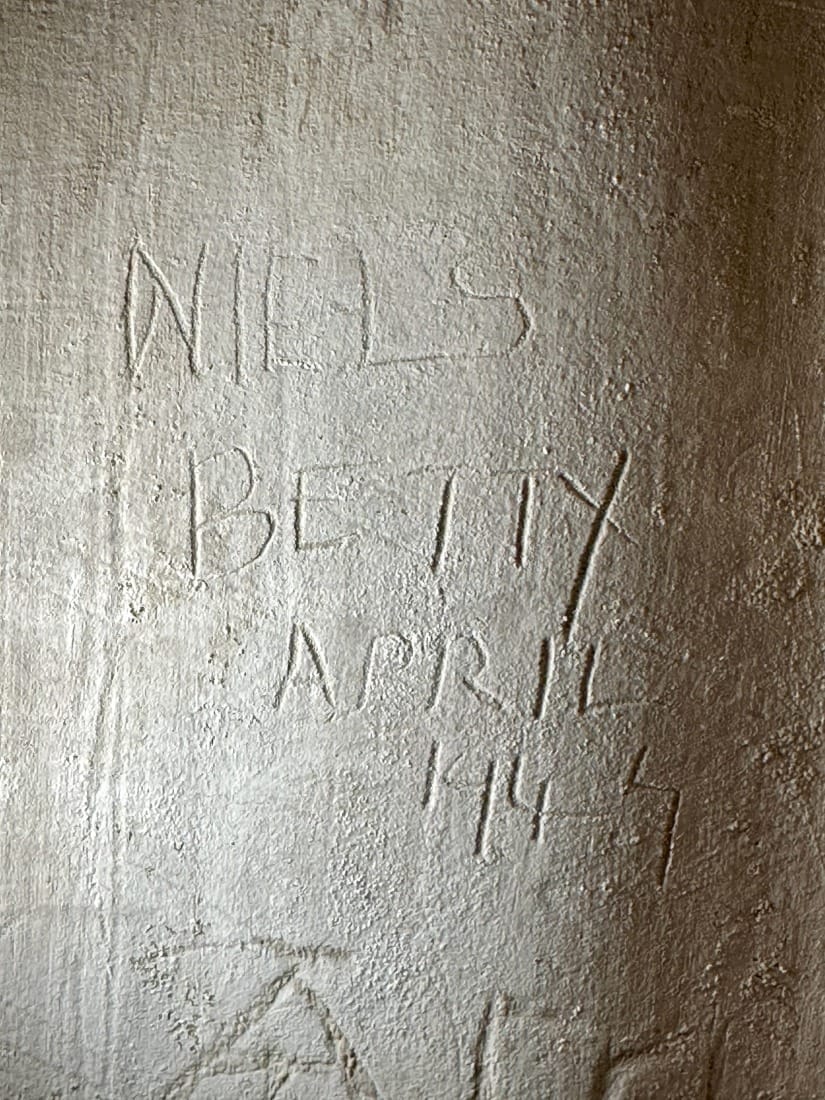

Later in the morning, I re-visit some C20th graffiti that I photographed several months ago. Although they’re 600 years apart from their predecessors, there’s not a single micron between the hopes and fears of the generations that carved them.

What is utterly fascinating to me is how, with graffiti viewed as a key part of the fabric, these buildings unravel in space and time. Buildings like St. Mary are a vast cognitive reserve, a wondrous and sophisticated cosmos of quivering emotional intelligence. This building is full of tiny signatures, a lexicon that betrays the aggregate human attempt at survival in desperate times. They reveal a voicefulness and a need for connection and recognition.

There are whispers in these walls that are telling. The graffiti at St. Mary’s reminds me of how insignificant the present is when compared to the immense framework of time. The present (with all the saints, the sinners, the lovers, the haters, and the tyrants that are jokers and the jokers that are tyrants) is like a tiny island in a vast archipelago full of untapped wisdom.

I’m reminded of some words by Apache, Cibecue Horseman: Dudley Patterson:

“Wisdom sits in places. It’s like water that never dries up. You need to drink water to stay alive, don’t you? Well, you also need to drink from places. You must remember everything about them. You must learn their names. You must remember what happened at them long ago.” *

The answer to our present woes is out there, writ large upon the places that our forebears left behind. It tells of the things I found in Ashwell bakery: community, coherence and connection.

We must cherish and protect these places as if our lives were etched upon it.

*Quotation is taken from Wisdom Sits In Places: Landscape and Language among the Western Apache by Keith H. Basso, 1996, University of New Mexico Press.

Access all Eustace Articles Here:

Photographs and words by Andy Marshall (unless otherwise stated). Most photographs are taken with Iphone 14 Pro and DJI Mini 3 Pro.

Member discussion