This article is a part of the Eustace collection - aimed at helping others create counter-narratives to threats to our historic environment.

Learn more about EustaceAccess all the Eustace articles here:

Wells Cathedral Light Refinery.

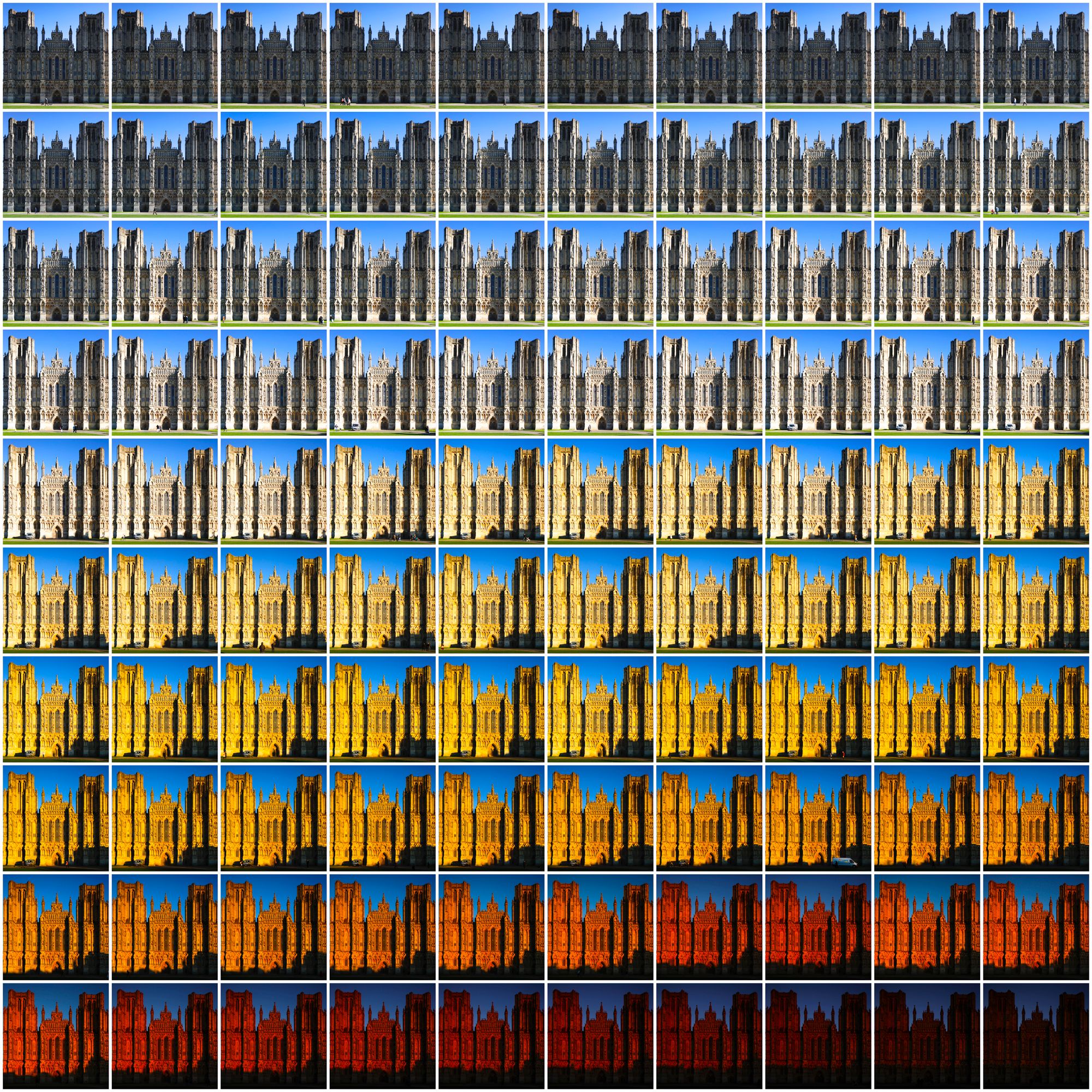

It's a cool but bright day at Wells and my task is to spend the whole day time-lapsing the interaction of light with the glorious west front of Wells cathedral.

I set myself up with tripod camera and butty box on the green, but before I do so, I grab a coffee from a shop along the street (it's no longer there) and tell the warm and welcoming barista about my task.

"I'll come and bring you a coffee at lunch time!" she says. How kind.

Wells is one of the best facades to learn and witness architectural light craft.

The cathedral nave and twin towers form a powerful structural backdrop, as imposing as a mountain bluff, with deep cut recesses set between buttresses decorated with slender Purbeck columns. It is garnished with a host of Gothic artefacts perched like guillemots on a cliff face. During the Middle Ages, the whole facade would have resonated with sound and colour.

With the added ingredient of time, the complexity of carvings, niches, and patterned surfaces creates a layered soufflé of light. A full clear day is the perfect time for the full spectrum of light to be revealed.

At first, with the sun rising behind it to the east, the facade is muddied - set in shadow - more a blurred massing than a collection of details.

Then, as the sun moves around and rakes against the facade, the massing starts to extrude extremities in the form of buttresses.

The buttresses are part of a great tectonic storyboard populated with statues of knights and saints set in gabled niches

The light finds the outline of the niches first and the effect is striking, like burlesque strip lighting embracing the principal protagonists.

Beyond the darkened recesses of the facade, after debuting the great and the good, the glimmer works its way into the textured folds of its occupants.

A matter of half an hour turns a solid buttress into a doyley of perforated light. It untangles slender shafts of Purbeck from rivulets of cusping and expresses them in a dotted morse code along the full height of each buttress.

The sense of grounded massing gives way to a feeling of elevation and linearity - slender forms, isolated by the light, reaching upwards towards the recessed towers.

Next, the central gable, which holds the biographical nucleus of the facade, is gently revealed as if a darkened veil is being removed.

At first the Apostles feel the warmth of the sun and then, in turn, Christ in Majesty surrounded by seraphim.

The presence of the building changes in a way that suspends belief in the previous incarnations: ‘Was the cathedral really dark and sombre just minutes ago - or was that my imagination playing tricks with me?’

‘Was the cathedral really dark and sombre just minutes ago - or was that my imagination playing tricks with me?’

Under the hardened light of mid-afternoon, when the shadows are the shortest, the next chapter of the story is revealed along the full width of the cathedral: that of the Resurrection, with figures clambering from their earthly graves both literally and metaphorically into the light.

Full and hard revelation gives way to a series of chromatic renderings with the facade moving from soft white to yellow ochre, cadmium orange and then a bloodshot vermillion.

Before receding back under the weight of darkness, the light is in such a quandary of rapid change that the stone facade appears in a state of flux - an architectural equivalent to the northern lights.

Such a fission of transitional light is guilt-edged by the monumental backdrop.

It is one of the seven wonders of the photographic ether.

"Before receding back under the weight of darkness, the light is in such a quandary of rapid change that the stone facade appears in a state of flux - an architectural equivalent to the northern lights."

On the day, this ecclesiastical light spectacular stopped people in their tracks, fixated by the fluidity, trying to fathom the mechanics of this wondrous event.

At Wells, the viewer is being set up in a medieval virtual reality: an actor within the vast stage set out before them - a stage storied through the remarkable stone carvings that depict the whole expanse of time - from the creation of the Garden of Eden to the Resurrection.

Across a building extruded from the Triassic and Jurassic this isn't just a parable of faith, but also the story of the cosmos itself and our part in it.

"Across a building extruded from the Triassic and Jurassic this isn't just a parable of faith, but also the story of the cosmos itself and our part in it."

And then, there is the story of light and its optical complexity. A light parasitic - the building being the primary host to its antics.

Silhouetted by back light, thinly veiled by a misty light, silvered by reflected light, perforated by a raking light, elongated by a discerning light, exposed and flattened by a hard light, softened by a suffused light, given majesty by golden light, and, finally, infected by blue light in a brooding melodramatic dénouement.

After all these years the building still speaks - it speaks of its creators, of the creation and of creativity.

At the end of the day, after absorbing the plots and subplots that had been cast before me, I was left with an even greater puzzle: how best to share the beauty of what I had witnessed over time?

Unlike the complexity of what I’d just seen, the answer was glaringly simple...

...leave it to the photography.

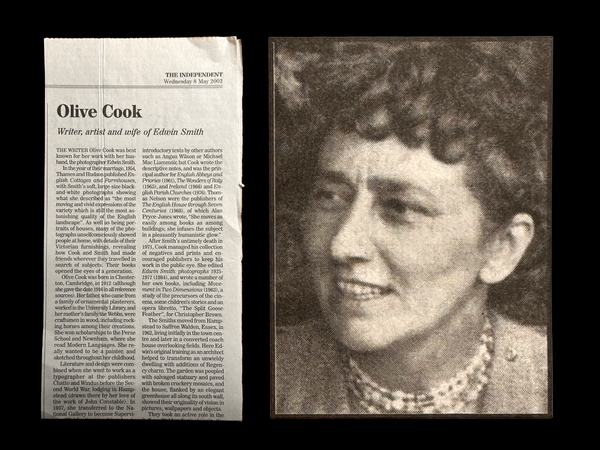

Photographs and words by Andy Marshall (unless otherwise stated). Most photographs are taken with Iphone 14 Pro and DJI Mini 3 Pro.

Member discussion