Hiraeth

There are just a few places I have visited that seem to be accessed via a time slip. Normally, it isn’t a sudden thing, but a transitional feeling experienced while driving or walking towards a place. For example, in the Langstrothdale Valley, in the Yorkshire Dales, it occurs somewhere along the road to Hubberholme. There’s a sense of chronological delamination—a stripping back of time. On the road to Cooling, in the salt marshes of Kent, it feels more like an evaporation of the present day, as if the landscape itself exhales history, leaving the present thin and fleeting.

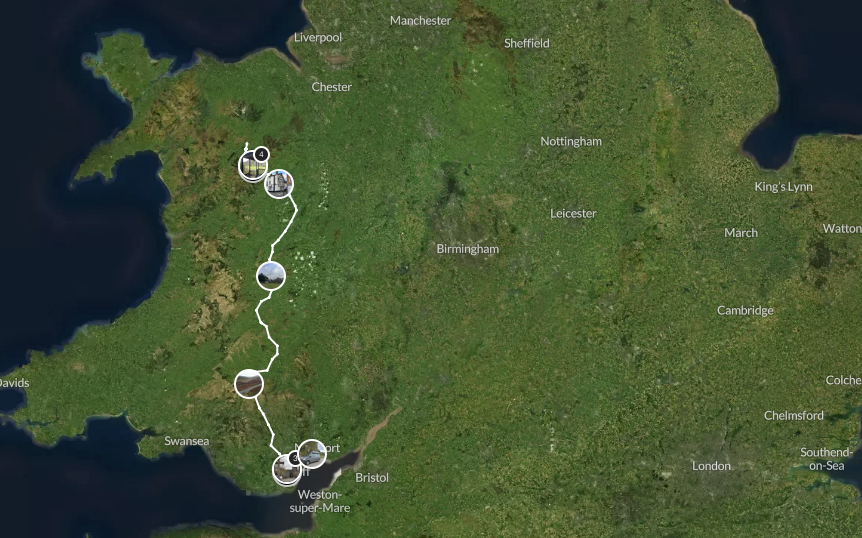

On my most recent journey to St Melangell’s in North Wales, the time slip was more defined. It occurred at Llangynog, on the turn into the single-track road that took me deep into the fold of the Tanat Valley. As soon as I turned onto the road and passed the church, there was a marked change in atmosphere.

Travelling along the lane to St Melangell’s is an act of filtration, a redaction of modernity. The pressing matters of the day are pared down with each passing turn. The landscape provides a correspondence with the transition of time—the valley bottoms out into flattened serenity, as the Berwyn hills rise like embattlements pitched against any sense of doubt as to the magic at play.

When I arrive at St Melangell’s, I’m welcomed by Christine and Karen. They tell me that it’s shooting season. The shots that ring out temporarily break through the sanctity of this place.

It was to be a hunting expedition in the 7th century that helped define Pennant Melangell. Legend has it that Brochwel the Prince and his party were hunting hares when they came across a young girl in a copse, praying with a hare hidden in the folds of her clothes. The dogs would not approach, and the horses were unsettled. It was the first human contact for Melangell, who had lived in the copse for 15 years. She was an Irish princess estranged from her country. Brochwel thought it a miracle and granted the girl sanctuary, giving her the land where she established a church and convent. Melangell became the patron saint of hares. Her shrine is one of the most evocative places that spring from the times of pilgrimage—it might have been ported from an apse in Rome.

It’s a story that stirs something deep in the human psyche: of compassion, of harmony with nature, and of sanctuary. I’m reminded of some words by Diane Kalen-Sukra:

“Offering sanctuary is a revolutionary act; it expresses love when others offer scorn or hate. It recognises humanity when others deny and seek to debase it. Sanctuary says ‘we’ rather than ‘I’. It is belonging—the building block of community.”

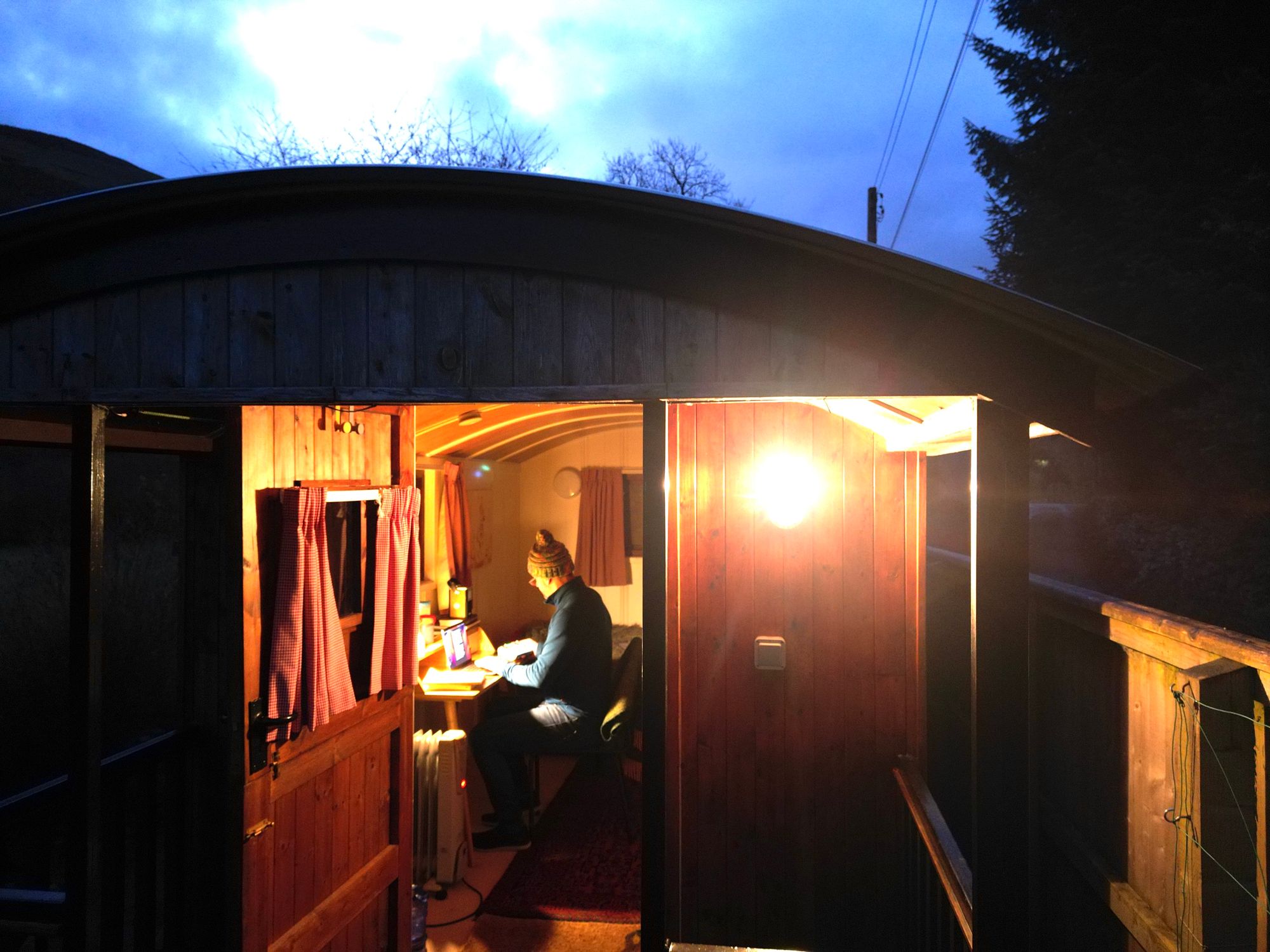

I enter the shepherd’s hut at St Melangell’s and make it my sanctuary. I hang my coat and empty my bag. I place my books on the bedside table, my shoes at the end of the bed. I perch my radio on a shelf and my MacBook on the desk. I look inside the drawers and fidget with the heater. Settled, I lie on the bed and listen to the cackle of pheasants out along the valley. Then, with time on my hands, I sit at the desk and begin to write.

I’m writing again.

After a while working at the desk, I notice a book placed on the table to my left called A Welsh Childhood by Alice Thomas Ellis. A previous occupant of the hut has left a note inside. It reads:

“There is a word in Welsh, hiraeth, which is a lifelong yearning for what is gone or out of reach. And in a place like this, we have moments of consciousness when we realise that time passes and will never come again.”

There is hiraeth here, but there’s also a comforting bend in the river of time that seems to slow things down. The church is rooted in generations of occupants who have each left their mark upon the furniture and walls. Outside the church, we are reminded of a deeper time: three yew trees that are 2,000 years old, surrounded by an oval Bronze Age boundary and a slip of land called the sanctuary.

I’m grateful for places like this, and grateful to Melangell and her story, to Christine and Karen and Mick (who showed me the way), and to the unknown occupant who took the time to share the spirit of this place. They unwittingly gave me sanctuary—a place to write.

I’d like to leave another word for this place: a Gaelic word, caol áit—a thin place—where the membrane between heaven and earth is so thin that you could almost touch it.

📍More Loci:

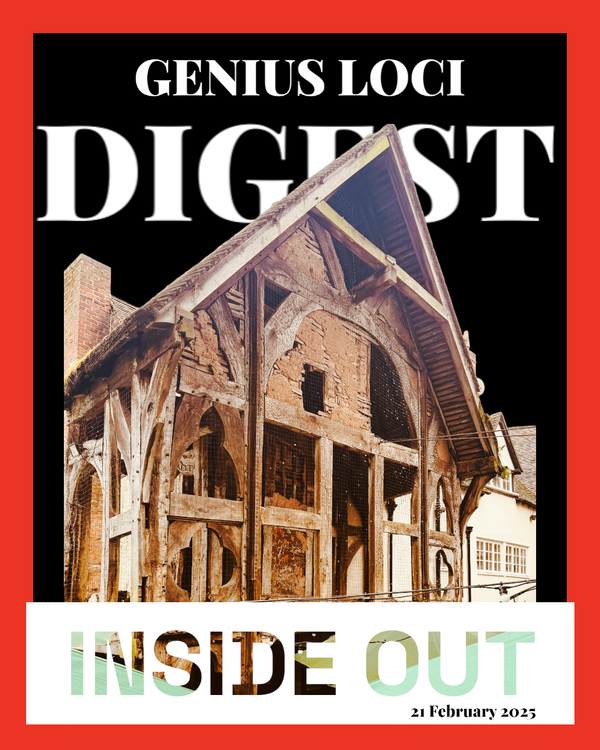

Subscribe to my Genius Loci Digest for free

'This Digest helps keep the past alive as a memory bank. Many of the answers can be found in the wisdom that sits in places, because buildings that survive from the past are the mouthpiece of history. In this Digest I tell stories about them and my encounters with them.'

SubscribeSpirit of Place * History * Material Culture * Heritage * Continuity * Photography * Travel * Architecture * Vanlife * Ways of Seeing * Wellbeing * The Historic Environment * Churches * Art * Building Conservation * Community * Place Making * Alternative Destinations * Hidden Gems * Road Trips * Place Writing *

Member discussion