Each week I send out a short, fresh reflection from the road – photographs, sketches, and observations from old places that still have something to teach us. What follows is a moment from that ongoing journey.

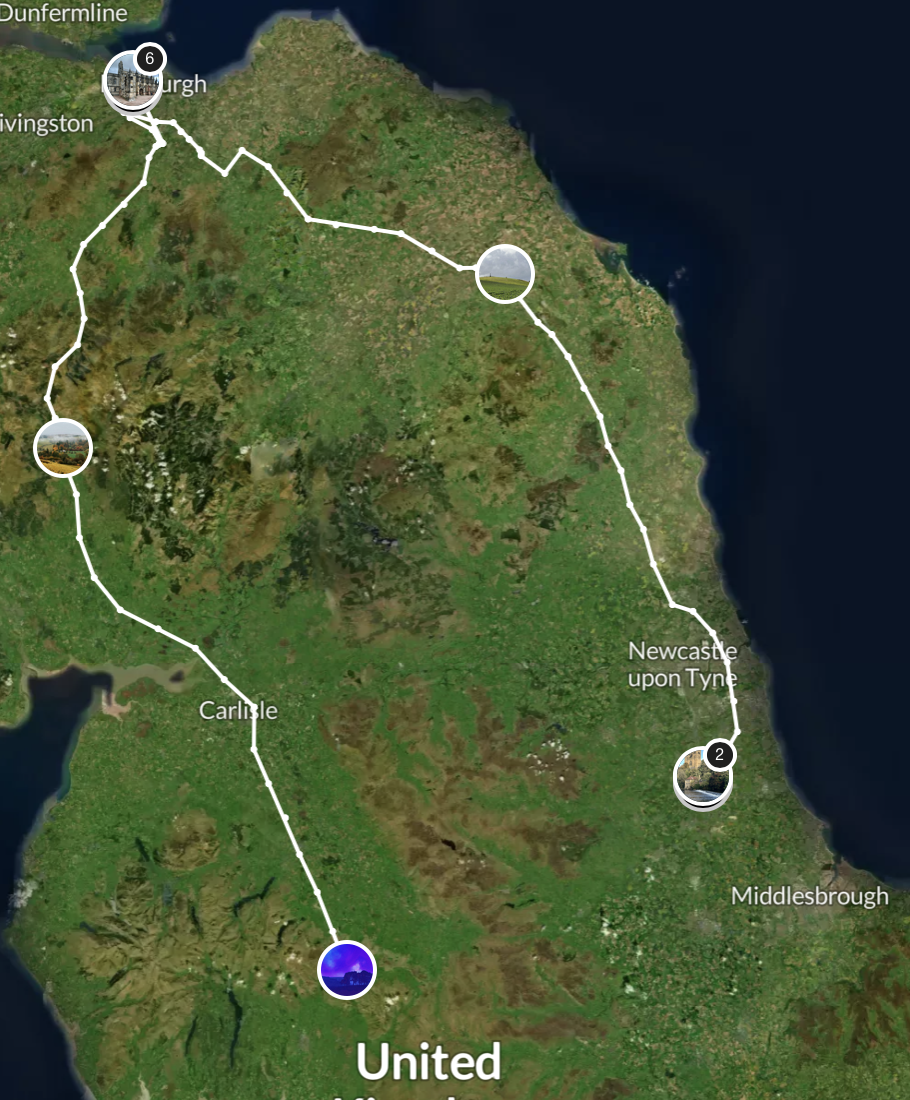

From Edinburgh, I take a circuitous route down the east of Scotland, through Flodden into England, skirting Alnwick, and finally reaching my destination: Durham.

I visit the cathedral late in the afternoon when things are a little quieter. It’s there that I become mesmerised by the arcading in the Galilee Chapel. At first, I can’t put my finger on why, but the pattern and syncopation of the arcading tug at a memory from my teenage years – a place with a similar style: the Alhambra. These kinds of connections ignite something within.

I think this visual and connective way of observing might be a by-product of my work, where thousands upon thousands of patterns and styles have been embossed onto my memory through my lens.

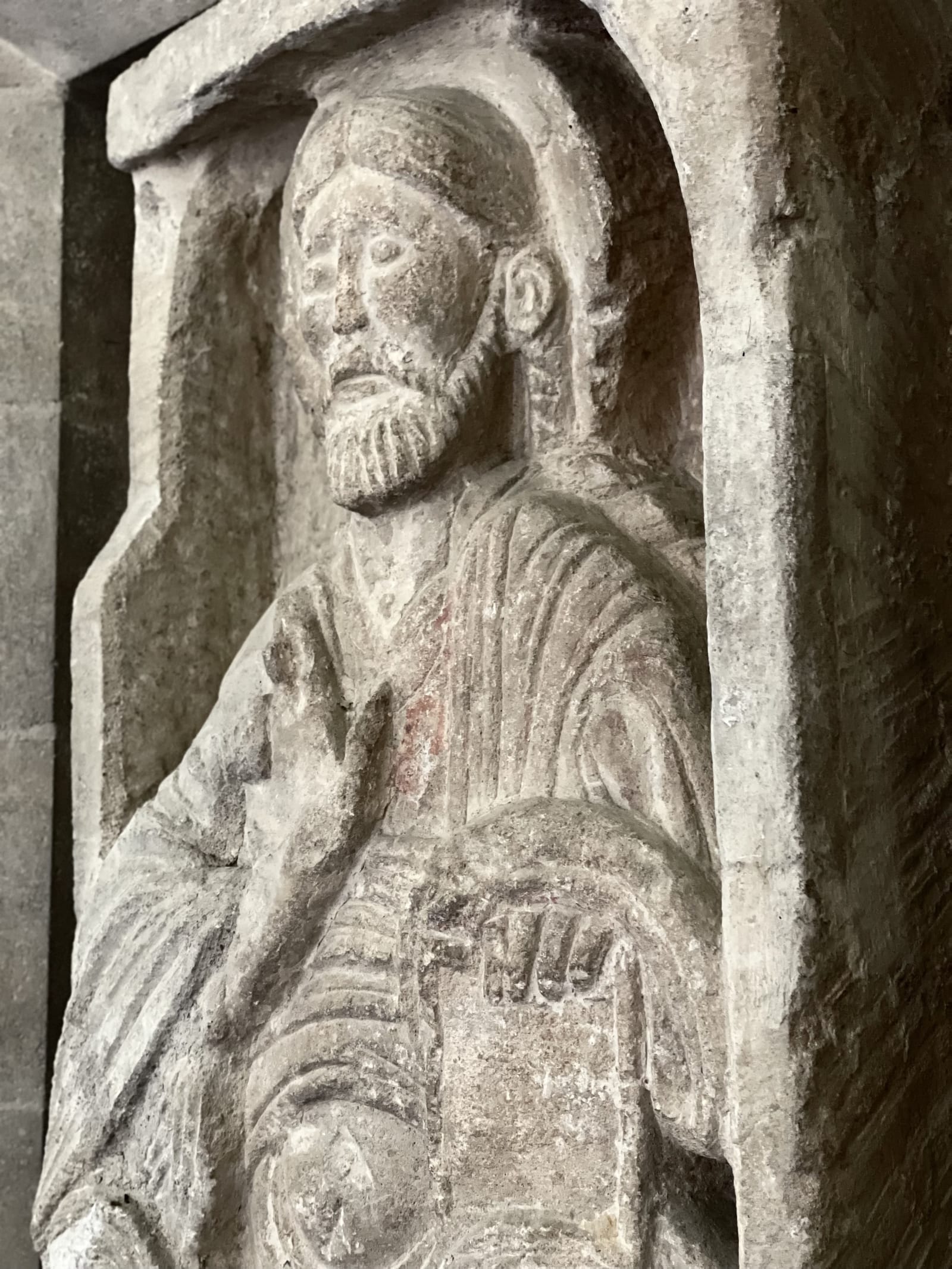

Recently, during a visit to Manchester Museum, I came across a sculpture of Bodhisattva that struck a chord with me in the same way as the arcading at Durham. Again, I had a memory of seeing something similar. Scrolling through my gallery of images, I found a photo of the Anglo-Saxon Christ in Majesty from Barnack. In terms of their origins, the two sculptures are poles apart, yet they share similar visual cues and patterns. In this context, at least, they are connected.

These visuals instigate an intriguing path of enlightenment. The Bodhisattva, dating from between 100–300 BC, originates from ancient Gandhara (in modern-day northwest Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan), a region along the Silk Road – a melting pot of cultures with direct links to Greece, Asia, and China. It represents a being on the threshold of enlightenment who chooses to delay becoming a Buddha in order to help others. Similarly, the Christ sculpture depicts a god made human to aid in the salvation of mankind. Their forms are also strikingly alike: rotund bellies, flowing robes, hands held up in gestures of blessing and fearlessness. The Christ in Majesty belongs to a genre that traces its roots back to the Byzantine style. Both the Bodhisattva and the Christ sculpture bear the influence of Greco-Roman antiquity. Perhaps even more powerful is their innate adherence to Fibonacci’s sequence and the golden ratio – patterns that tie the two epochs together.

These patterns tell their own story. They speak of a melting pot of cultures, of association, assimilation, and diversity. They connect the vast stream of human consciousness that flows through these objects.

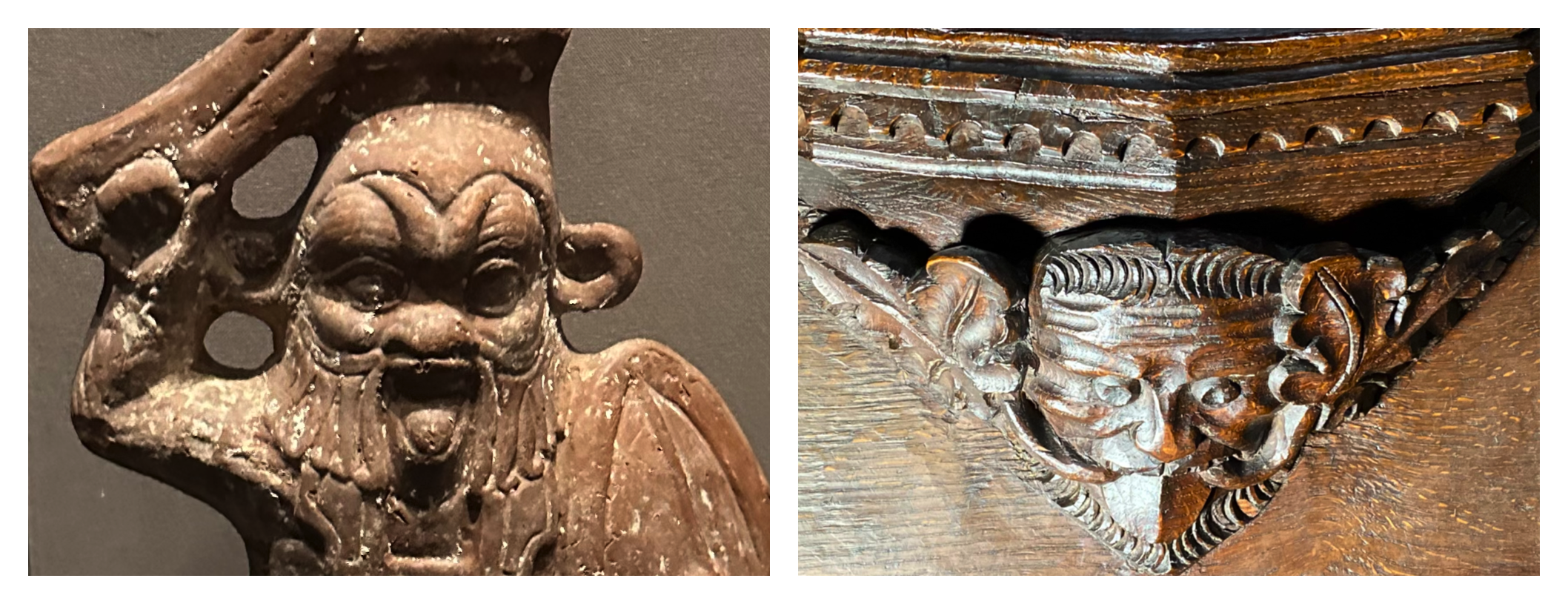

I think of the things I have come across that are visually connected: the hybrid gods found in the ancient burial chambers of Egypt and the foliate heads that adorn our cathedrals.

I think of the hieroglyphics of the pyramids and the apotropaic symbols in churches.

Moving forward in time like a vast glacier, our material culture continuously pushes forth to the present – bringing with it materials, textures, details, and texts that still have the power to move and inform us. What remains beyond the surviving stone and mortar is a kind of cultural moraine, one with the latent power to bypass our biases and connect with us emotionally.

I’m reminded of Lily Bernheimer’s words in The Shaping of Us:

“The usability of the casement window, the beauty of Venice, and the durability of ancient stone walls are achieved thanks to the small and repeated contributions of many people over many years. We love old buildings because they envelop us in patterns we understand intuitively.”

Like the imprint of sand left behind by the receding tide, our absence etches patterns of meaning that linger long after we’re gone.

What is surprisingly powerful in all of this is that, if we listen to our intuition and cultivate ways of seeing that are both observational and connective, we possess an antidote to the algorithm, to fake news, to polarisation, and to the distrust of modern times. There is a tried, tested, and locked-in wisdom in the small and repeated contributions of many people over many years – one that can provide a countermeasure to our present woes.

I’m not naïve – I understand that human interaction has been shaped as much by conflict as by cohesion, as I’m reminded by the Flavinus tombstone at Hexham Abbey: a Roman standard-bearer trampling a Briton. But even in that brutal message, I find in the golden ratio and the patterns beneath it a salient reminder that our vast repository of material culture reflects an innate and incorruptible aspect of humanity – one that thrives on cohesion and common ground.

Travel with me weekly - subscribe to my Genius Loci Digest for free

Each week, this Digest offers a small pause – photographs, sketches, and reflections from historic places that still carry meaning. It’s a weekly practice of noticing, continuity, and learning to see more deeply.

Subscribe📍More Loci:

Spirit of Place * History * Material Culture * Heritage * Continuity * Photography * Travel * Architecture * Vanlife * Ways of Seeing * Wellbeing * The Historic Environment * Churches * Art * Building Conservation * Community * Place Making * Alternative Destinations * Hidden Gems * Road Trips * Place Writing *

Member discussion