This is an excerpt from a book I’m writing called A Singular Point of Light. It charts my journey from breakdown to wellbeing through the mediums of photography and place. For World Mental Health Day.

“The body is amazingly stubborn when it comes to sacrificing itself to the annihilating directions of the mind.” Sylvia Plath

On a damp autumnal afternoon in the late 1990’s I had what I now realise was a mental breakdown. I had been working for a family roofing firm and, during a long and stressful summer, I’d convinced myself that the vitality of youth would get me through the inherent risks of being in charge of a sub-contractor in a sticky industry. I was wrong.

After feeling unwell at work I drive home in a state of hyper-tension, gripping the steering wheel, sat bolt upright in the car. The last thing I remember is having a series of chest clenching palpitations in the hallway of my home.

I wake in a curled up foetal position in the corner of my bedroom. I’m not sure what’s happening. My instinct is to try and break out of the paralysis that’s pinning me to the floor — but I can’t. I’m frozen in a bile-throated, living rigor-mortis. I feel like a bird tumbling through a hedge after being shot in mid-flight. It takes every cell in my body to bring about a state of calm. Besieged by an indeterminable terror, a dread of upsetting the status-quo leads to cramps in my calf and thighs.

The first thing that resolves is the sky outside, although my view through the window is incoherent and prismatic. Time seems to warp in those first few moments. I take deep breaths into my stomach to help settle my thoughts. Every breath, every movement, every nuance has its part to play. Even though I feel like I’m dying, my senses are piqued and raw. I lie on the floor for an hour or so, and it’s only when the sun shines through the curtains behind me that I feel a subtle shift in atmosphere. My mood changes. I notice shapes appearing in the room and patterns defined by the sunlight: the shadowed edge of the bed, the sharp cut of the sill, the line of slates on the rooftops outside. Ripples of warmth percolate up from emotions that tap into the roots of my childhood. Through a kind of visual anchoring from one location to another, I coax myself back into the present and stand up.

Euphoria sets in — I have achieved the mental equivalent of climbing Mount Everest, but shortly after, there’s a brutal drop into reality. Getting to this point has taken what feels like a lifetime’s effort.

To spill this occurrence beyond the boundaries of my mind would lead to shame and horrors untold. The shock of this new state of being turned me into the purplest of worlds, a feeling that I later discovered had a name: depression.

The blackness was a ghost inside. It wasn’t articulate or transparent; it didn’t break legs or cause cuts and bruises. Instead, it immobilised my thoughts and actions, any combination of which — such as getting out of bed — brought on a sense of foreboding. I later told a therapist that my depression was like being stretched between the open bomb-bay of a war plane: hanging on with dread, beneath an explosive cargo, whilst life hurtled past below.

I barely survived the next year. I scraped an existence by just being: turning up to work when directed, and allowing others to fill in the blanks as to what they expected of me. I was a parent too, and the inability to engage with the joy of parenthood increased my melancholia. The thought of taking my life seemed perfectly sane and logical. Surprisingly, there wasn’t the drama attached to it like I’d seen in the soaps. The overwhelming compulsion was to feel nothing. But I held on.

During that year I experienced everything in the round with periods of cyclical survival. Each day, from a point of sombre introspection and self-recrimination I called up every trick in the book to find sparse places of comfort. The places I found were like the slender ledges of a rocky precipice. Exercise created temporary outcrops that helped me cling to life. Running gave me credence through action, and let me sieve the anxious dross out of my head.

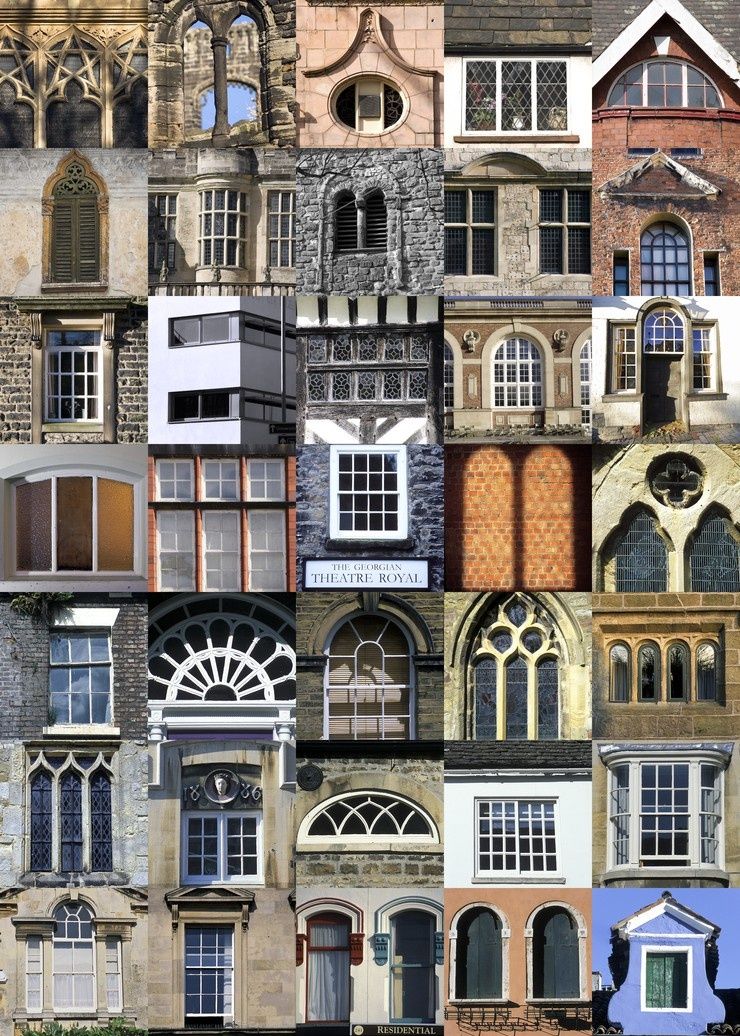

What was left was a guiding intuition — little pearls of light. I went back to the time during my breakdown when I medicated on the shapes, shadows and spaces of my surroundings. Sometimes during a run, I’d stop in the street, summon up the memory, and look at the buildings. Bizarrely, the window patterns and rooftops, the brick, glass and stone conjured up vague connections with the pearls of light.

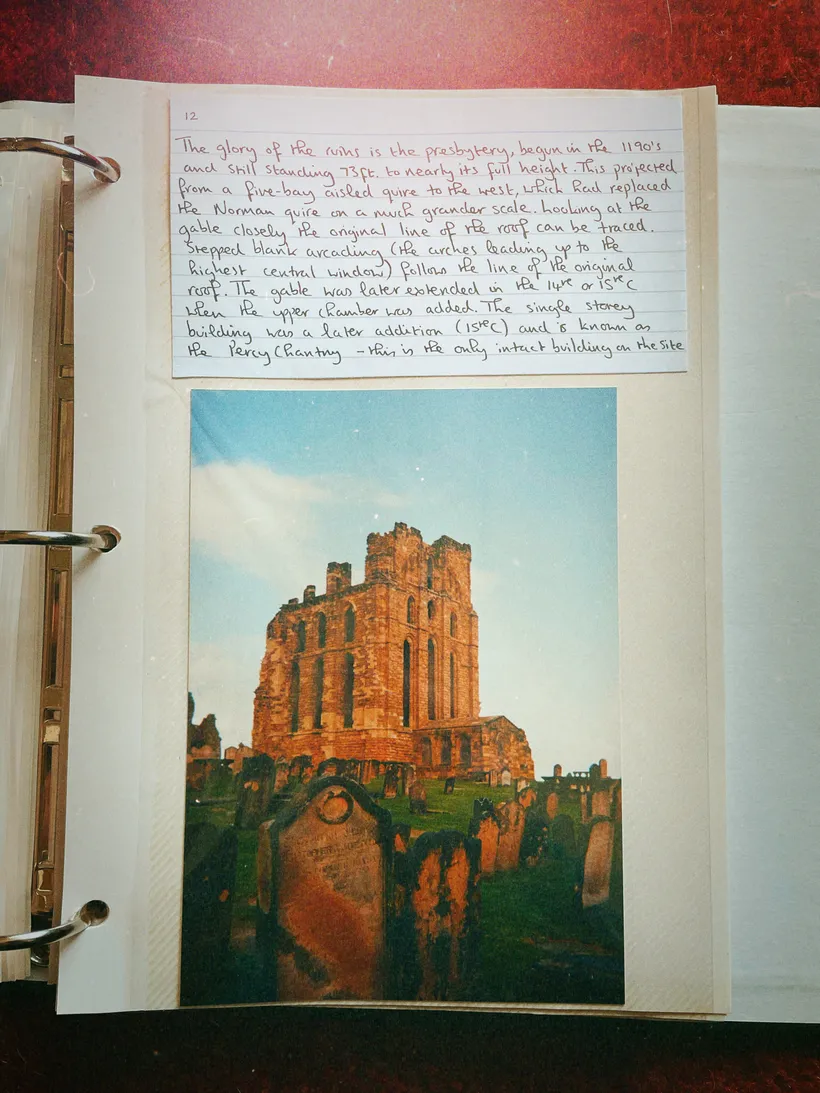

It was a frustrating process, a kind of journeyman therapy. At times I’d find a soothing poultice for my raw thoughts through connecting with places, only to lose the bond through a smog of self-loathing. But, slowly, I built up a catalogue of places and buildings that meshed together a framework that gave me purpose. A transparent need began to emerge: to find out why the combination of light, line and form gave me comfort. A residue of the melancholy remained, however, until a trip out to Tynemouth Priory where, as well as a notebook and pen, I took a camera.

I drove up along the A1 to Tynemouth in transition. My mood tripped between elation and despair. The weather was mixed. When the sun came out I felt content and in control, but as soon as it disappeared, I felt anxious and otherworldly. Woven into the thread of my recovery was a hypersensitivity to my environment that left me feeling as if my soul needed sunglasses.

After arriving at Tynemouth, my immediate compulsion was to head back without disembarking. My journey was turning into a worrying setback, but I stopped the car and paused for a moment. Eventually, I coaxed myself out of the car and walked over to the headland. I felt exposed and vulnerable, but I was encouraged by the view of the priory with the sea beyond. Exhausted by the hyped-up mental activity I found a place to sit and gather my thoughts.

With my anxiety dissipating, I pulled a pen and pad from my bag and started sketching the view. When I placed the pad and pen back into the bag, I glimpsed the camera and took it out. After figuring out the dials and buttons, I stood up, placed the camera to my eye, lined up a detail of the priory and took a photo.

For several minutes I scanned the arcading for another opportunity. Then I walked out to the headland, and with my back to the sea, framed the priory — but something wasn’t right. For the first time out of thousands of times since, I stopped and turned, observed the rolling clouds, and waited for the sun to appear. When it emerged from beneath the clouds I turned, re-composed, and, with the warmth of the sun on my back, took the photo.

For those moments, something miraculous had happened. During the action required to take a photograph, I had let go of my anxious self. From that day onwards, the veil of depression lifted. Photographing the priory had released me from my mental prison.

This is an excerpt from my draft book which I am serialising for Parlour, Piano Nobile and Palazzo members of my Digest. It is serialised every month in the Member's Patina Edition Newsletter. Become a Member.

Why not come join me and see the world through my lens?

Subscribe for freeMore about how the digest came about:

Member discussion