“Those who don’t believe in magic will never find it.” Roald Dahl.

✨ Many will feel the pull to hurry past these words, gripped by the restless urge to scroll onwards. But should you find the courage to linger, to resist the tide of haste, you will be performing a quiet kind of magic - a small rebellion against the tyranny of time itself. For in crossing this threshold, you take the first step on a path where minutes stretch, hours unfold, and the ordinary slips quietly into the extraordinary.

☕️ Make yourself a brew and hunker down - for this is going to be a roller coaster ride through time.

📌 If you find yourself caught in the rush, with the clamour of the day nipping at your heels, do not worry. Simply bookmark this page, as you might leave a lantern glowing softly in a darkened room - so you can return when the world is quieter, and the magic is ready to meet you where you left it.

📮 And if, by the end, you find yourself a little more enchanted, a little more immersed - as though time itself has whispered in your ear - consider passing this magic on. Share it with a kindred spirit who might just need a gentle reminder that time is not always something to be chased, but something to be discovered.✨

How I became a time traveller - and how you can too - (a three minute read)

“The hurrier I go, the behinder I get.”

— Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll

As we busy ourselves planning our days, our minds shape the future: the people, the tasks, the obligations, the brief flashes of downtime. There’s a certain logic in how we govern our lives - a sense of time parcelled neatly into portions, each one tethered to the next.

But, it may come as a surprise to some, our linear view of time isn’t rooted in science. Physics tells us that time bends and warps. Neuroscientist David Eagleman calls it "a rubbery thing." Our current relationship with time is a condition of modernity -a response to our growing obsession with mastering it, clocking it, calendarising it.

Working in the historic environment as a photographer has altered my perception. Time, in these places, is layered and unruly - elastic, surprising, alive. It’s made me realise that we’re living in an age of fettered time, where time is appropriated and shaped by invisible forces beyond borders. Today, we inhabit time-X, TikTok time - a fractured landscape cauterised by the constant ping of the next notification.

Time, in these places, is layered and unruly - elastic, surprising, alive

Other cultures experience time differently - cyclical, woven with the seasons, anchored in natural rhythms. The Romans saw the future as fixed, untouched by present actions. J.B. Priestley likened time to an omelette. But it’s Shakespeare who comes closest to my own experience:

"To stamp the seal of time in aged things."

My view of time has been significantly impacted through the act of photography and, in particular, my experience with historic places, especially churches. Whilst photographing churches I’ve encountered time as elastic and malleable. It's not a religious thing - it's more about the temporal. It’s an experience that has elevated my wellbeing as well as the way that I relate to our world, and I’d like to pass it on.

It’s an experience that has elevated my wellbeing as well as the way that I relate to our world, and I’d like to pass it on.

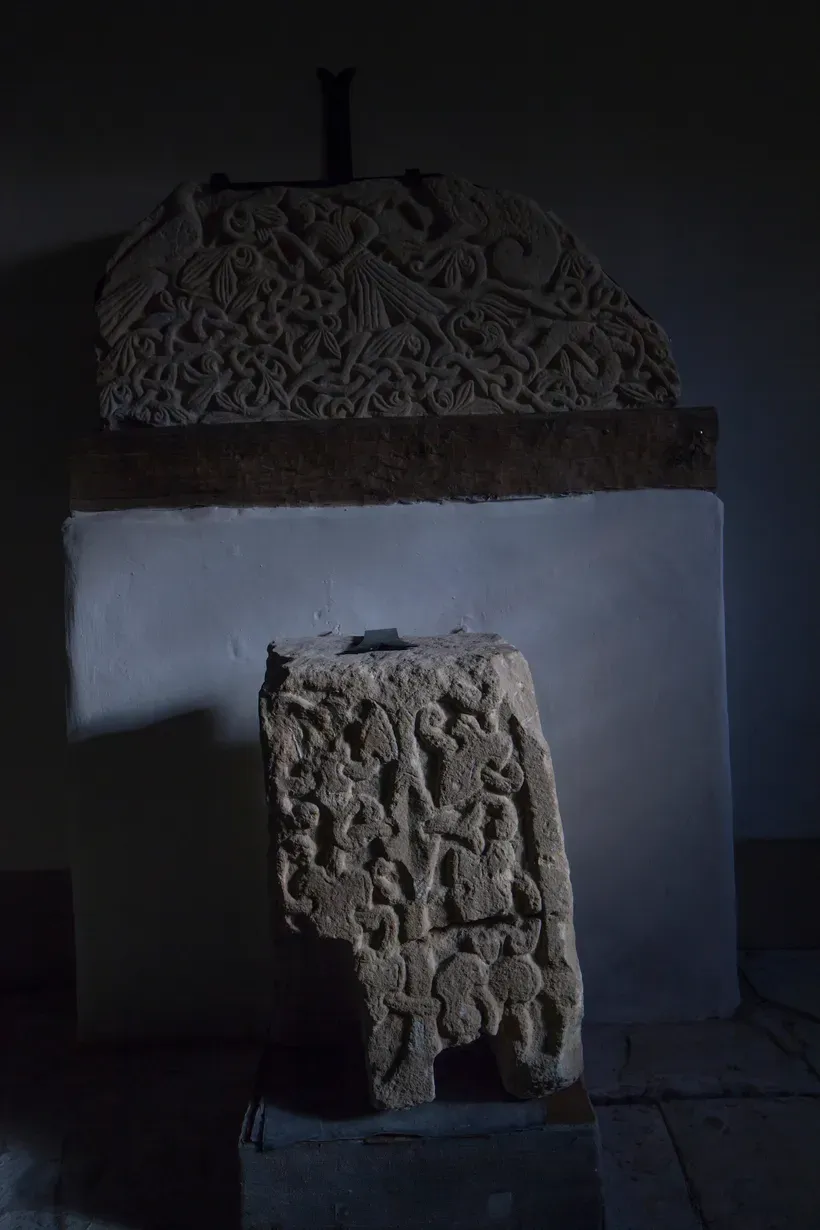

Whilst a photograph can hint at time’s passage, churches press the grubby nose of the past right up to the present. Whereas photographs can halt time’s procession, churches suck it in with an imperceptible hoarding of time. In these sacred nooks a gathering takes place. It’s here that an ocean of generations come to shore - the monuments, inscriptions, and carvings; the rood, encaustic and vaulting - washed up like driftwood.

Alongside the grand memorials, they also cradle the accidental - traces left by ordinary lives: graffiti etched by fleeting hands, vernacular art, local idioms woven into wood and stone. These are the quiet testimonies that slip through the cracks of official history, yet endure, whispering across time.

John Betjeman called them "mothering spires," places that have cradled communities through centuries of trial and triumph. Standing within them, the past and present align. Our own troubles seem to dissolve in the company of collated wisdom. These buildings whisper: "Others have stood where you stand. They endured. So will you." They are tachographs of the human condition, slowing down time’s relentless churn.

Fettered time demands we compress complexity into 30-second soundbites, shrink thoughts to fit 280 characters, and disconnect from the richness of past and future. It scatters the mind, frays attention, leaving us untethered from meaning.

Below I've listed some magical places, curated by our forebears, that allow us to escape fettered time, to bathe in an alternative chronology. In medieval times, people found refuge by seeking a sanctuary knocker on the door of a church. Perhaps now, more than ever, these buildings have the potential to become sanctuaries of the mind for all faiths and none. To draw from their experience as well as our own; to heal, soothe and place the present into perspective, nourish us with the past and, without the shackles of a fettered mind, overcome the challenges that our future brings.

✨An Antidote to Fettered Time: 10 Places that slow down time. ✨

Here are some of the most remarkable places I’ve had the opportunity to visit over the past 25 years of my career - places that have touched me, places with a magical presence, places that confound the time continuum.

At the time of writing all the places mentioned here are accessible to the public. Please check before you visit. I have included a map with the location of all the places mentioned here at the end of this passage.

St. Michael's, Upton Cressett, Shropshire.

Set within a landscape that feels like a medieval stage set, the journey to reach it becomes part of the story. Hollow lanes twist and fold through the countryside, guiding you not just through space, but through layers of time. Each bend in the road, each sunken track bordered by ancient hedgerows, feels like an invitation to step sideways into another world.

Inside, the church reveals itself - not with grandeur, but with a quiet gravity. It is small, just a modest two-cell structure, yet it holds a weight that isn’t measured in stone. The air feels thick with the residue of lives once lived, prayers once whispered, footsteps once echoed across the encaustic.

While setting up my camera in the first light, I watched a mouse slip along the altar rail - a brief movement, indifferent to the centuries gathered around it. It felt like a living thread stitched through the fabric of time.

As I photographed, I felt time wash over me - not in a torrent, but as softly as the morning light spilling across the chevrons of the Romanesque arch. In that moment, the past wasn’t behind me; it was all around me, woven into stone and shadow.

St. John the Baptist, Inglesham

Some places are saturated with meaning, and it just takes a few silent, uncomplicated moments to stop, see and listen to what they have to say. St. John the Baptist in Inglesham was a place that taught me how to see.

This little church in Wiltshire struck up a conversation with me as soon as I entered through the porch. It told me something about its history and how it was built, how it was consecrated and how it has survived.

Perhaps Betjeman was inspired by Inglesham when he wrote in his Churchyards poem:

"Our churches are our history shown

In wood and glass and iron and stone."

Time is captured within the architectural narrative, but also within the honeycombed pockets of space. Fettered-time-washing takes place through the process of entry from one space into another. I walked into the nave, then the side chapel and then back around towards the altar. After that - I walked to the right and gazed into the eyes of an Anglo Saxon Mary and Child.

St. Patrick, Patrington, Yorkshire

The interior is sublime. There is a sense of balance and harmony inside, attuned to human scale and proportion. This is a big church, but there is a sense of being cosseted from one space until the next.

When I first entered through the north porch my gaze was drawn through a forest of columns, each more intricate and interwoven than the last. Together they formed a canopy that was as comforting as a woodland.

The carvings of jocular smiling figures (some are of the villagers) added more warmth and humanity.

This place is all about connective time - time that has deep roots - that grounds and steadies the soul.

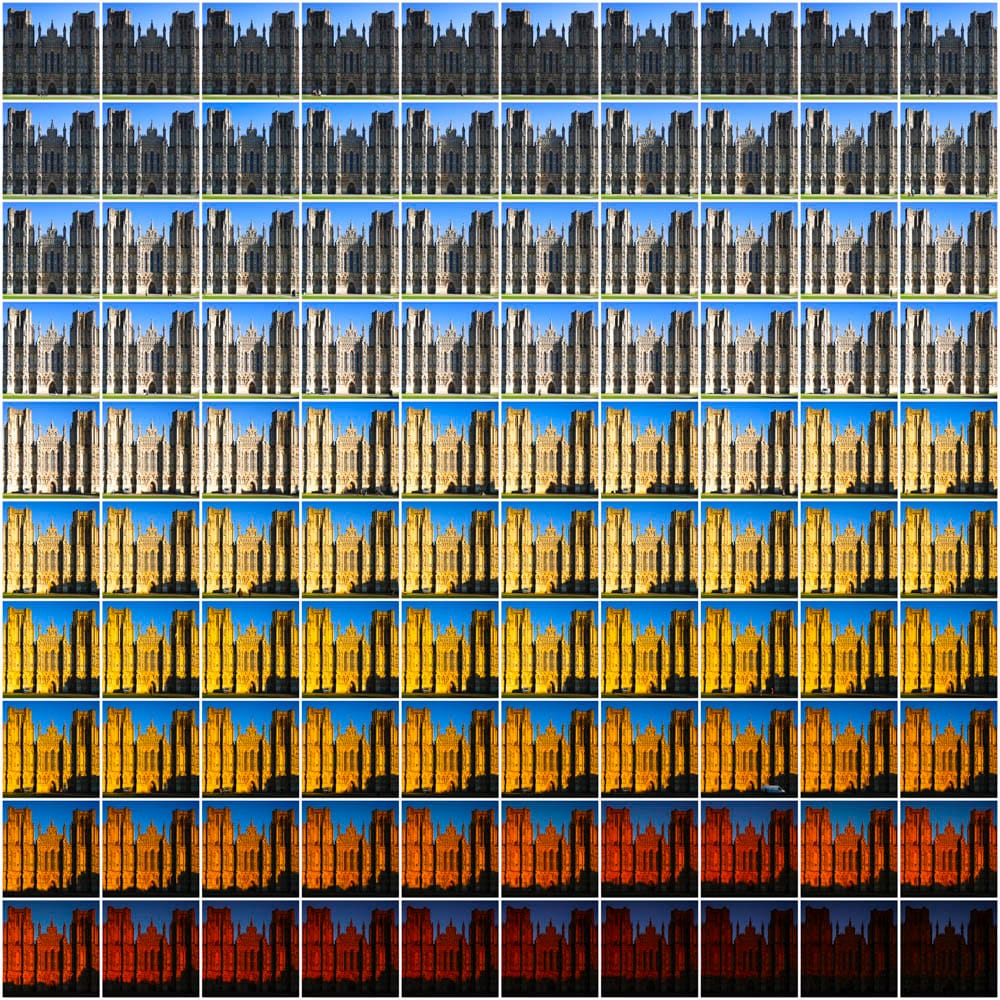

Patrington is best visited in autumnal or spring light when it reaches inside and touches the walls opposite and articulates the curvilinear shadows of the Decorated.

St. Peter's, Windrush, Gloucestershire

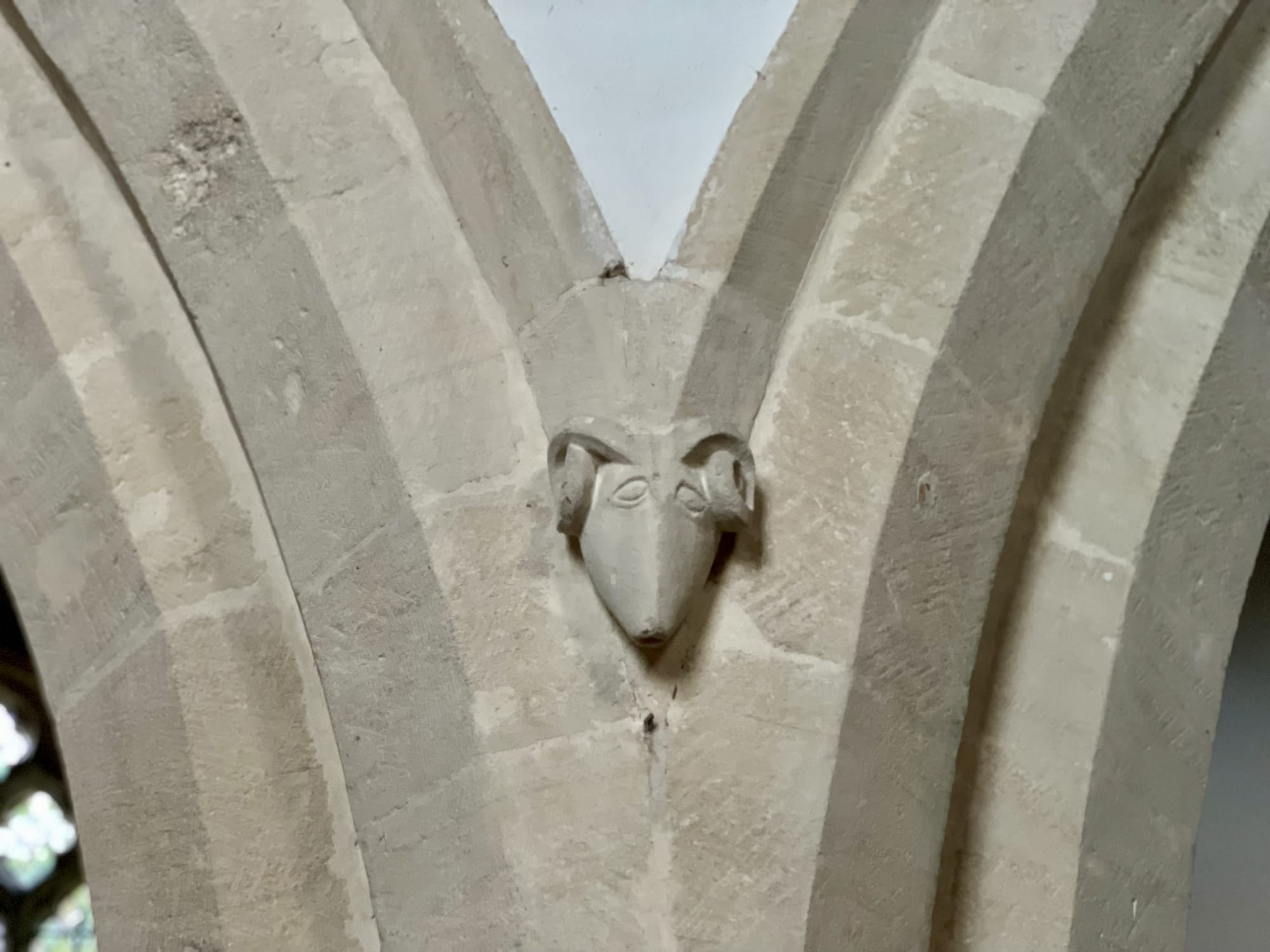

St. Peter's, Windrush helped me experience cosmic time - time across the universe.

It was here that I stood with iPhone camera in hand waiting to photograph a sheep's head. Whilst taking the photograph in the darkness of the nave in a flat light, I was struck with the odd notion of the future colliding with the present.

About 40,000 years, 8 minutes and 20 seconds before that moment, several atoms at the core of the sun, about 150,000 kilometres from here, were subject to an act of nuclear fusion. The resulting light, which had taken around 40,000 years to sift through the suns layers, glinted across the universe in about 8 minutes and found itself heading towards a small island in the northern hemisphere.

15 seconds later it was over the great county of Gloucestershire and 3 seconds after that it took a precarious path over the Windrush village roof-tops. It then percolated through an intricate tapestry of leaves, the handmade glass of the west window, and the dusty motes of an ancient nave. About 1 second before it hit the sheep’s head, I put my iPhone away and took one last look at the carving.

Then it hit.

Instantly the animal was alive - its head was a blintering mass of moving light which spilled out onto the column behind, begetting the head with a sparkling, animated body.

About 600 years ago, when the light I saw on the sheep was part way through the sun’s corona, a medieval mind might put such animation down to God’s work: a message from beyond. In the here and now, my scientific mind forced me to acknowledge the how and why of what was happening, but something deep inside me curtailed my Darwinian bent, and for several minutes, immersed me in the magic of the moment and the wonder of cosmic time.

A video of the Windrush light show

Can you help keep me time-travelling into deep time?

Become A MemberAll Saints', Billesley, Warwickshire.

This was my first revelation. The first time that I was introduced to the nuances of time.

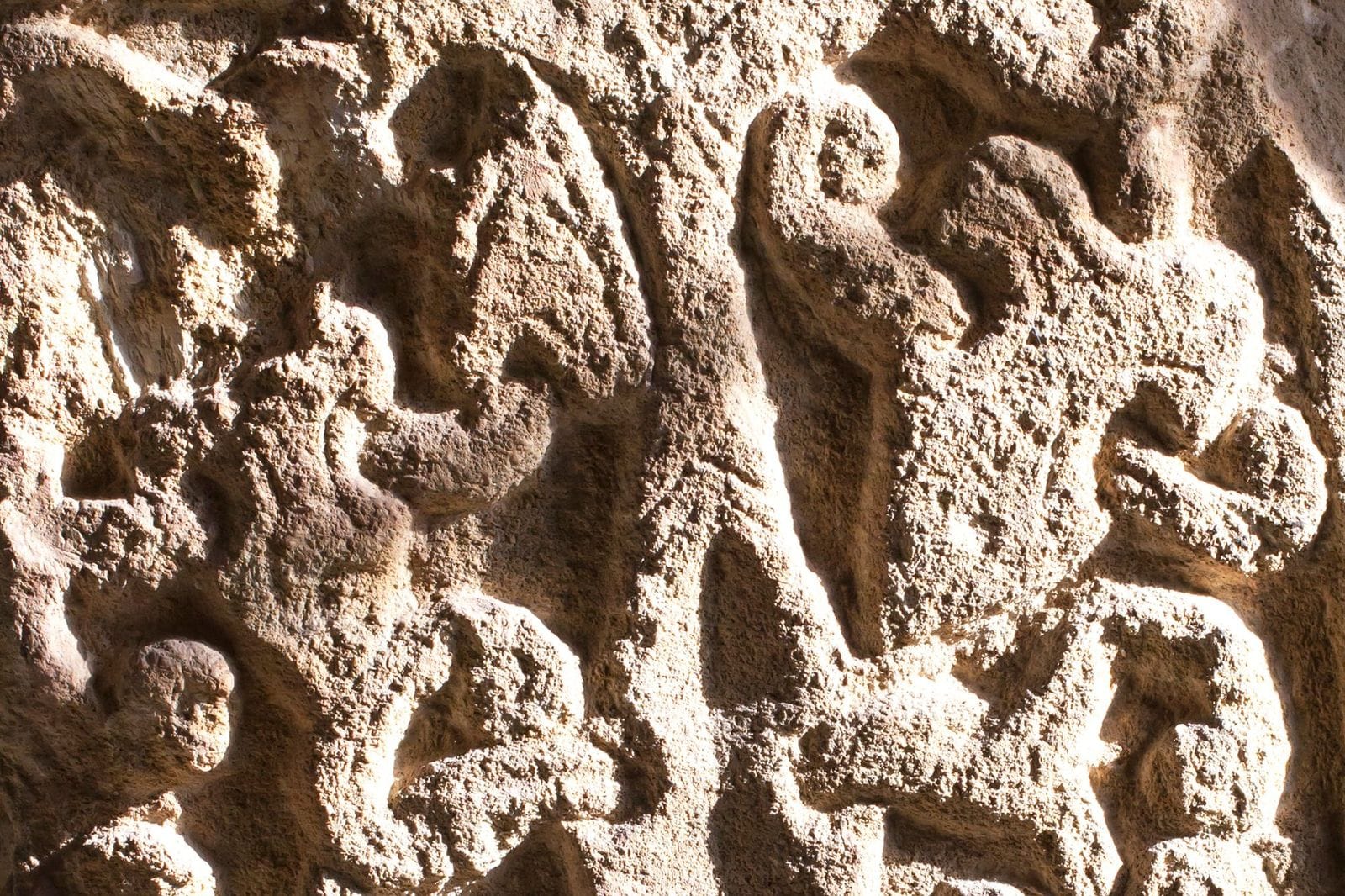

Here, I photographed a Romanesque carving. To me, at the time, it looked like a clumsy piece of work, but later on in the day, when the sun had swung to the west, the lump of stone took on a completely different aspect, and I sat for an hour and watched its story unfold.

At first the surface looked stagnant and isolated until the light pooled along the transept floor. Then, with lime-wash as an unscripted reflector, a harsh light induced an abstract three dimensionality. Its surface was more faceted than textured - a prologue to the story unfolding. Several minutes later, the light moved onto the tip of the stone and a shift in colour and texture took place.

Like a precious baubled ring, the carving became the clawed setting, the movement of light upon it the jewel.

The passage of light over the stone invoked a momentary communion with the Romanesque carver. The piece of stone, with the assemblage of skill, time and light had propagated an act of visual magic. The warmth of the sun and its passage over the stone had unravelled the carvers intent: the visual storyboarding of the surface. For the briefest of moments, I had parity with a world that operated upon a different orbit: an elongated time-scale.

Nellie's (The White Horse Inn), Beverley

Yes, it's not a church! Churches aren't the only time hoarders on these isles.

The White Horse Inn, otherwise known as 'Nellies', has an interior which is still lit by gaslight. A visit to the hostelry involves an ocular passage of lights, a visual photosynthesis of surface plane and detail which is completely reliant upon vaguely subdued pockets of light.

Light levels have not been standardised or subject to European norms. The building has grown organically over hundreds of years culminating in a Dickensian warren of corridors and cosy fire-lit rooms. Entering Nellies involves stepping down into post medieval floor levels mixed with a pupil dilating mellowed light.

During my visit I sit (with a pint of mild) in a small room set obliquely off a wainscot corridor. It’s square in plan with a trinity of light sources in the form of a fireplace, gas lamp and sash window. There is a silvered mirror above the fireplace. It is worn and speckled around the edges like the chest of a thrush. The frame is adorned with bold and gaudy swags of fruit. An oak settle is steadied upon an encaustic floor by a folded beer mat. The anaglypta wall it leans against is tobacco in colour.

At first, I sit there bathed in the half-light of a winters afternoon. The room is dominated by the light from the sash. A chair, looming from a darkened corner, casts shadows which are sharply defined near their originator, but increasingly muddied and vague the further they are cast. The light is harsh and rude. As the flat light gives way to twilight and the sash light yields to the ochre glow of the gas lamp, a transition takes place. The scene softens, the gaudy colours de-saturate and the emboldened details dance in the fire-light.

There is a link between the glowing snugs at Nellies and the caves of Lascaux which have painted on their walls ice age depictions of aurochs, horse and deer. They are painted directly onto the rock face and it’s thought that flickering torch-light, in combination with the daubed irregular surfaces, created a cinematic quality that elevated their presence.

The flat surface pattern has no truck here at Nellies, only patterns that are etched or moulded or in deep relief. They are intended as visual triggers to embolden, to filter, to hunt for the paucity of light and in turn (as at Lascaux) create a wavering Serengeti of light. Ornaments are no longer defined by their form, but by the light they reflect and absorb, shaped by shadows and coloured by an amber glow.

What we have here is a particular domain of light which seems to foster a bonhomie that slows time down - this place is the nearest I've felt to time-travel. A gregarious saturation in a Dickensian past.

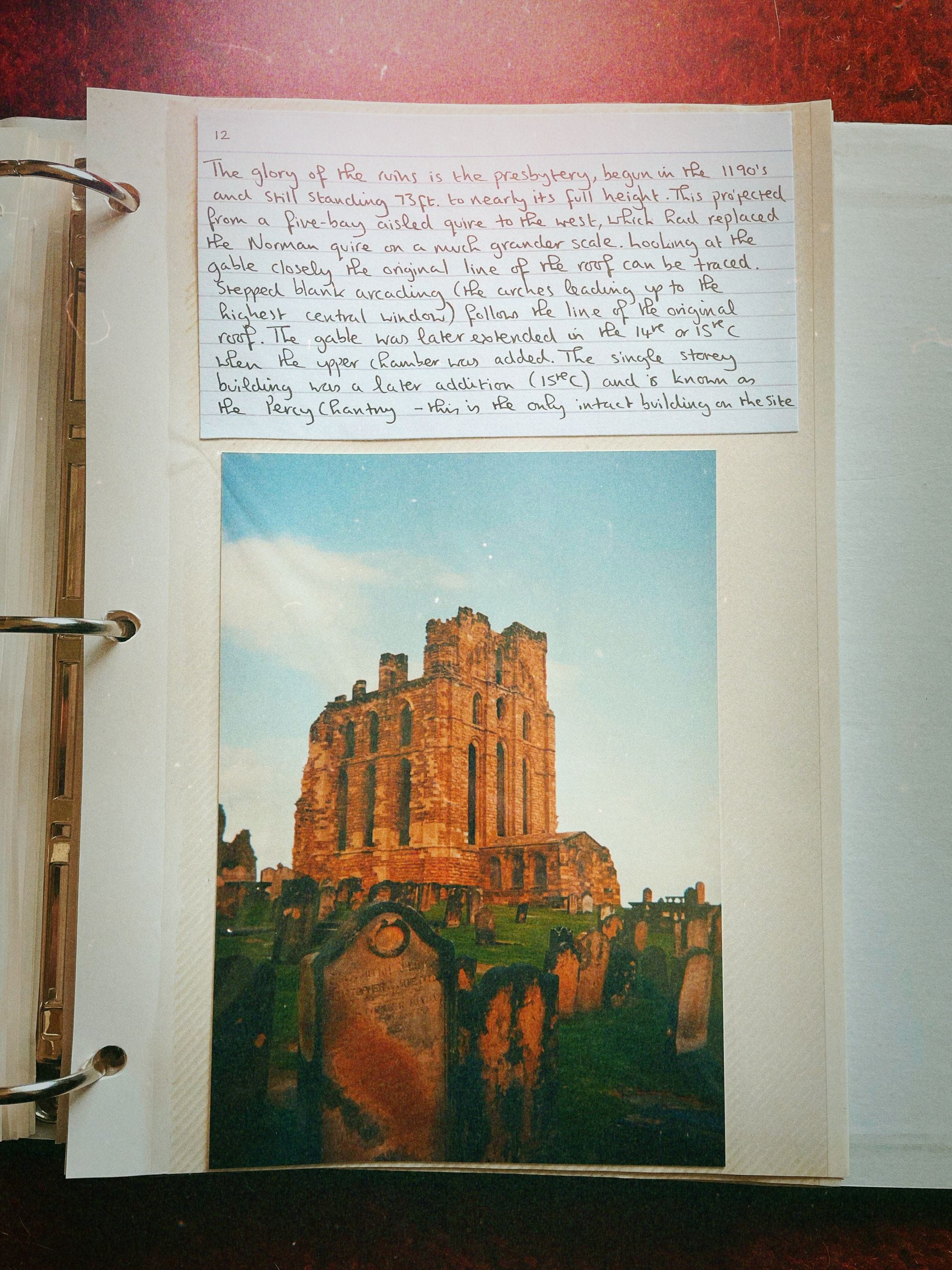

Tynemouth Priory, Tyne and Wear

This was a very personal journey, many years ago, after suffering a break down and subsequent depression. Depression felt like wading through molasses. It slowed down time to such an extent that, at times, I could feel every heart beat, every flicker of my eye lids.

My visit to Tynemouth not only released me from time's drudgery, but kick-started a new life where time seemed to offer promise and hope for the future. Tynemouth Priory turned out to be an additional complication in the time-piece that was particular to me.

I didn't have a digital camera then - so I processed the photographs and marked the significance of the visit by placing them into a folder.

Here are the words from my draft book:*

I drove up along the A1 to Tynemouth in transition. My mood tripped between elation and despair. The weather was mixed. When the sun came out I felt content and in control, but as soon as it disappeared, I felt anxious and otherworldly. Woven into the thread of my recovery was a hypersensitivity to my environment that left me feeling as if my soul needed sunglasses.

After arriving at Tynemouth, my immediate compulsion was to head back without disembarking. My journey was turning into a worrying setback, but I stopped the car and paused for a moment. Eventually, I coaxed myself out of the car and walked over to the headland. I felt exposed and vulnerable, but I was encouraged by the view of the priory with the sea beyond. Exhausted by the hyped-up mental activity I found a place to sit and gather my thoughts.

With my anxiety dissipating, I pulled a pen and pad from my bag and started sketching the view. When I placed the pad and pen back into the bag, I glimpsed the camera and took it out. After figuring out the dials and buttons, I stood up, placed the camera to my eye, lined up a detail of the priory and took a photo.

For several minutes I scanned the arcading for another opportunity. Then I walked out to the headland, and with my back to the sea, framed the priory - but something wasn’t right. For the first time out of thousands of times since, I stopped and turned, observed the rolling clouds, and waited for the sun to appear. When it emerged from beneath the clouds I turned, re-composed, and, with the warmth of the sun on my back, took the photo.

For those moments, something miraculous had happened. During the action required to take a photograph, I had let go of my anxious self. From that day onwards, the veil of depression lifted. Photographing the priory had released me from my mental prison.

*my draft book is serialised every month to Parlour, Piano Nobile and Palazzo Members.

St Ellyw's, Llanelieu (Llaneleu), Wales.

The road to St. Ellyw’s is a hollowed out single track - cut into the side of forests and fields. I sense that I’m getting closer to the church when the van starts to jitter across chevroned mud scatter, and soon the road dissolves into a farmyard with boundaries that are vaguely visible beneath the ochre clay that seems to abound in these parts.

The church lies within a scattered hamlet. I park next to the bridge over the brook and hike up the steep lane and position myself between the church and the Black Mountains, covered with a mantle of snow to the south. I always try and get a sense of a building before I photograph it. The boundary here is oval shaped, betraying a ritualistic landscape that is older than the church.

There's something special about entering a church. The best places evoke a feeling of transition upon entrance. There's no exception here. The view over to the east is divine: the medieval rood screen survives and is painted with ox-blood. Upon the screen is the presence of absence - a ghost-rood.

I notice that the door at St. Ellyw's is made of ancient wood, with a patina that's been curing for centuries. Once inside, I see a gap in the base of the door and a small hole half way up the door. A little later, whilst photographing a wall painting, there's some movement at the base of the door: a wren hops inside, slants its head at the tripod, and then flies up to the roof timbers. I realise that the hole at the base of the door is there because of local knowledge and not lack of maintenance.

A few minutes after seeing the wren, a slender shaft of light appears from the smaller hole in the door, capturing the dust motes in its rays. I look to where it’s landed - an orb on the wall to the left of the font.

I keep checking back on the light shaft from the door. The orb has reached the base of the font. The north wall is now a sundial, the liturgy secondary to horology - the font is a gnomon.

As the day circles around I continue with my work, remembering the words of John Ruskin when he first used a daguerreotype to photograph the buildings of Venice. He felt as if he were carrying off the palace itself within his camera. I too feel like a magician in places like this, capturing the magic of this space within the confines of my camera - bottled within the sensor.

It’s only when the light orb reaches the shaft of the font that I notice some movement within its sphere. I bend down to focus in, and realise that I’m witnessing an act of magic that has mesmerised human beings for millennia. The world outside has been transported along this shaft of light onto the font, the traditional place of new beginnings. The clouds in sharp relief are moving at a pace across the orb at the base of the font.

Momentarily, I feel a shift of perspective in this little church, shadowed by the Black Mountains. This precious incident of light has enshrined me within the intricate workings of a camera obscura. This little box with an ancient oaken aperture, has carried me off with the fixtures and fittings.

St. Melangell, Pennant Melangell, Wales

Travelling along the lane to St. Melangells is an act of filtration, a redaction of modernity. There is a time slip, of course, as you turn into the single lane track. The pressing matters of the day are pared down with each passing turn. The landscape provides a correspondence with the transition of time - the valley bottoms out into flattened serenity as the Berwyn hills rise like embattlements pitched against any sense of doubt as to the horological magic at play.

Legend has it that Brochwel the Prince and his party were hunting hares and came across a young girl in a copse, praying with a hare hidden in the folds of her clothes. The dogs would not approach and the horses were unsettled. Brochwel was told that this was the first human contact for the girl who had lived in the copse for 15 years.

The girl was an Irish princess who was estranged from her country. Brockwel, thought it a miracle and granted the girl sanctuary giving her the land where she established a church and convent. Melangell became the patron saint of hares and her shrine is one of the most evocative places that spring from the times of pilgrimage - it might have been ported from an apse in Rome.

Remarkably, the shrine has survived - it was found in chunks around the church fabric - post reformation, and re-built. It has the feel of a shrine in a Roman church.

I'm not religious, but I'm fascinated by places that tug on human emotions, whether it be a distant story of human endeavour or a surviving latch from a skilled hand centuries ago.

The church sits on an oval Bronze Age site which is guarded by a sentinel of yew trees - many of them reaching back to the foundation of the original pre-christian site. So the people that wandered these hills before Christ was born - saw the seeds of some of the yew trees that survive today.

The Yew Tree at Crowhurst, East Sussex.

How do you go about photographing such a thing of beauty? It is a building, a biota and a time-capsule.

I can't really remember the photography - the tree drew me in and for several minutes I felt like a puppet on strings with my camera in hand.

The tree brought about a kind of focused frenzy on the minutiae. There are some words in Alice Munro's "The Lives of Girls and Women" that touch upon the spirit of the day:

“…for what I wanted was every last thing, every layer of speech and thought, stroke of light on bark or walls, every smell, pothole, pane, crack, delusion, held still and held together, radiant, everlasting."

I'll just let the photographs weave their magic..

My interaction with the tree revealed a kind of visual and tactile storyboard. It told me that it was venerated because of its size and age, because of its gnarled associations with deep history, and because its surface, from certain vantage points, appealed to our innate Pareidolia.

I went inside and stood and looked up beneath the arc of its pan-millennium growth. I was at the centre of a living organism of reputedly four thousand years old. There was a strong sense of being embraced not only by the boughs of the tree but also by the past, the present and the future.

THE TIME TRAVELLER'S MAP

Below is a map of places that confound time and a description of how they impacted my relationship with time.

How fortunate we are to still have these places and spaces, the nooks and the crannies that allow time to dwell - so much so - that they can leave our thinking changed.

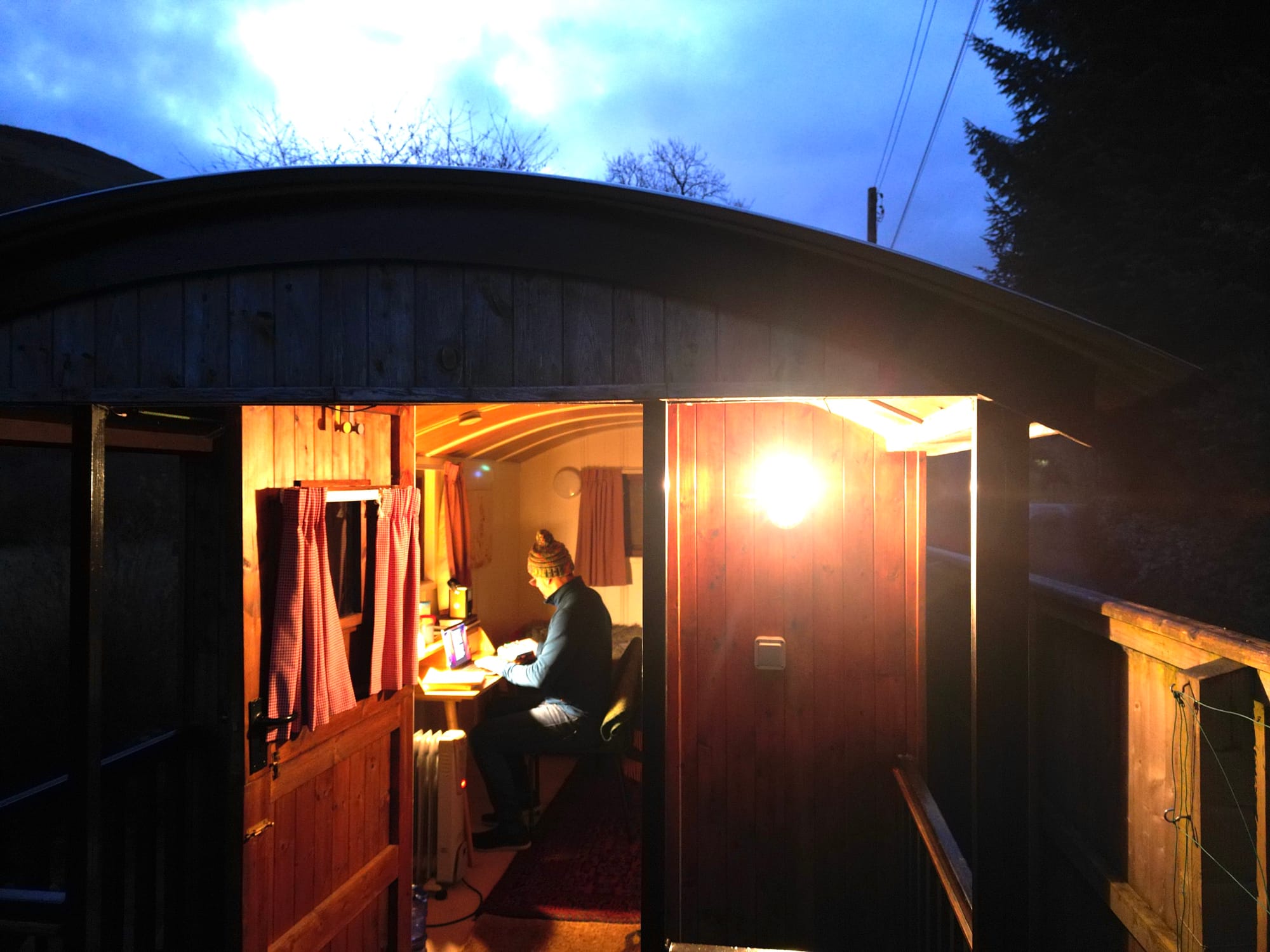

I can't tell you how much the van contributes to my wellbeing.

In the van I have built up layers of memories - that saturate it with meaning.

The van is a home from home and a place of permanence whilst the world travels by. In this way, it halts the progression of time - remaining a safe space to crawl back into after a hard days work.

When the curtains are shut in the van and it is in night-mode - I could be anywhere.

Time stands still.

From Breakdown to New Vocation: My Genius Loci Journey

This page is an update from a previous post, re-written, refreshed with new experiences and with new temporal locations.

Member discussion