Church of St Mary the Virgin, Llanfair Kilgeddin, Wales.

Survived the night in the van next to the church - only woke to take a pee. First light at the church is delicate. Cool crisp morning, dew on the grass, with the church silhouetted against the rising light. Blackbirds chirruping, a robin hopping and the sheep grazing in the field next door. Porridge and a cup of tea for breakfast.

My way of stretching in the morning is to extend the legs of the tripod, loosen up the ball-head and check in with the camera. It feels good.

The Usk is somewhere behind the church and is contributing to a reddening haze. Just before sunrise, as a fog bank rises in the next field, the wisps of cloud beyond the church take on a different aspect. They’re defined by a pinky outline. They’re moving quickly, their innards are nebulous with reddening light.

The day grows tall and the light is strong but flattened by high clouds. I move inside and photograph what feels to me like a glimpse into the twentieth century. Photographs in Athena frames record the planting of a tree in 1991. In the midst of a pandemic, it feels like a different age now - not too far away - but somewhere behind, just around the corner.

The light strengthens, and the sun gets a hold onto the day - the stained glass bleeds out into the window reveals and the pews are peppered with dappled light.

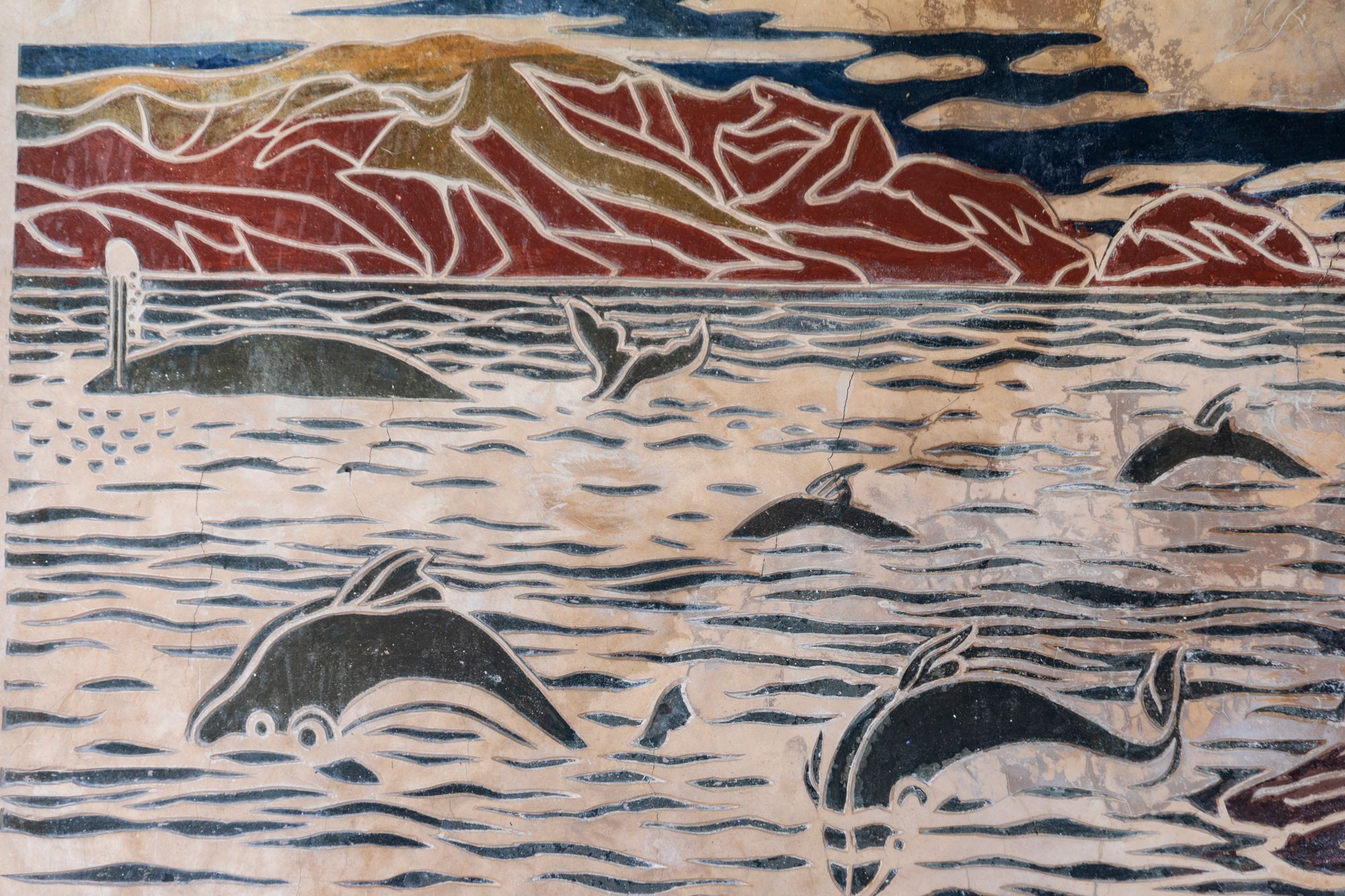

The minutiae of the twentieth century is framed by a nineteenth century sgraffito scheme etched into the walls. In the darkness of twilight, the walls reflect the diminishing light and they look like tribal tattooed skin - sweating - organic, alive. The scheme by the artist Heywood Sumner is a remarkable achievement. Sgraffito is made by layering different coloured renders onto a wall and then - before they have completely dried - cutting into the layers to produce an image or words.

The artist is constrained by his material, the ambient conditions and time - the render being prone to drying out at different timescales depending on its location. What is remarkable is that Sumner has not only provided a scheme that defines the interior, but it holds a lucidity and fluidity that only comes along once every century. This is a unique convergence of intellect, skill, time, place and material. The walls at St. Mary hold a complexity of human endeavour that will never be achieved again.

The last act inside is to photograph the organ seat - the presence of absence - the hint of contact - of continuity - the vapour of human activity.

There’s a tremendous sense of bliss after a satisfying day of photography, and it’s heightened by places that have walls that have absorbed the prayers and activities of a community for hundreds of years.

The afternoon is sharp on the eyes after working in the subdued nave. It takes time to adjust. I walk around the churchyard - checking on viewpoints I might have missed. I have a strong sense of having missed out on something, but I can’t work out what it is. I head over to the van and start to unload my kit when I look around and there it is. The light has given it a designation.

Along the churchyard boundary is a yew. Its great size has made it invisible - the boundary is enshrined in flecks of green and, through most of the day, the yew is camouflaged, part of a mass of trees to the south.

When I first recognise it, there’s a sharp intake of breath. Surely that isn’t one tree? It’s so big and so part of its curtilage that its textured countenance seems to be locked into the ground. I can’t see a way into the heart of it. I move closer and find a gap in the canopy, but instantly I’m rejected. My bag snags on a fallen branch that rises from the leaf mould like a briny serpent. This tree is a labyrinth - it’s testing me.

Eventually, crunching and tripping, cursing and prodding, I find a way through the tangled mass - but the tree only affords me a spot that denies me prospect of its size. I’m in suspension - held within its living branches and the scrub beneath. To move on, I have to shed my bag and tripod. There’s an overwhelming sense of the tree orchestrating my activities.

The tree is gargantuan. Its trunk several metres in diameter. I’ve visited yews half the size of this tree that are reputed to be a thousand years old. From its bowl rises an incoherent massing of branches, spurting upwards like a volcano suspended in animation. The air is still inside, but the tree is animated - the flux of it, its life force. It owns this spot - more than we do. It has survived our flaky systems of barter and enclosure and cost-benefit. In many ways it’s more successful than us. It has seen great civilisations pass by. It has seen Roman, Saxon, Norman - Cedric, Sally and Wayne.

For four seasons, through its flecked fringe, Heywood Sumner - dotted in plaster- walked past its bows. In the lifetime of this tree, his complexity is conjured into the blink of an owl’s eye, the snap of a branch.

After dropping the key back off at the farm, I drive over the bridge to the Usk and think that this is me and I am this.

My photography of this place, the logistics, the interaction, the process feels like a pilgrimage. This process - these connections with lens and place are what I'm about. At times like this - I’ve never felt so complete, so in the moment, so grounded.

Church of St Mary the Virgin, Llanfair Kilgeddin, Wales.

The church and yew at Llanfair Kilgeddin are of real beauty and rarity. Beyond the bucket list, they are both destinations that connect us with what it means to be human. Friends of Friendless Churches look after this place. Give them your support if you can. These places are more important than we realise.

Andy Marshall

is an architectural photographer based in the UK.

Member discussion